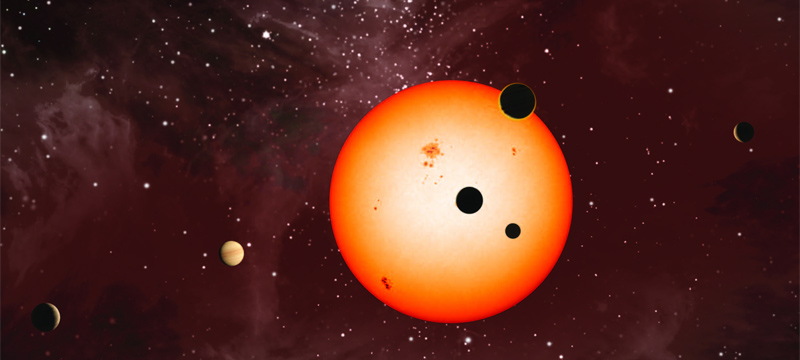

50 Billion Alien Planets May Inhabit Our Milky Way Galaxy

Our galaxy could be home to a whopping 50 billion planets, say scientists working on NASA's Kepler planet-hunting telescope.

While Kepler hasn't found nearly that many planets — to date it's counted 1,235 candidate planets — that cosmic tally is researchers' best guess, extrapolated from preliminary data. The Kepler spacecraft, which launched in March 2009, is the world's most sophisticated observatory dedicated to studying alien planets.

Kepler scientists presented an update on the spacecraft's findings this month at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C.

"I am really delighted to find that we are seeing so many candidates," said William Borucki, Kepler's principal investigator. "It means there's a very rich ocean of planets out there to explore."

Goldilocks planets

Kepler observes a large swath of nearby stars to search for signs that they might harbor planets. Though it can identify candidate planets, these must be confirmed by follow-up observations before they are pronounced fact. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

Of the 1,235 possible planets Kepler has observed so far, 54 appear to be at a Goldilocks-like "just right" distance from their stars where temperatures would be right for liquid water. This region is called the habitable zone, because for a planet to be habitable to alien life, it would probably require water.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Extrapolating to the Milky Way as a whole, the researchers predict that at least 500 million of the galaxy's probable 50 billion planets reside in the habitable zone. That certainly offers a hopeful sign for the existence of life beyond Earth.

Kepler has also identified 68 Earth-size planet candidates in its data set. Scientists think rocky planets like Earth are also the best bets for hosting alien life.

Earth-like planets

Yet to find a truly Earth-like planet — that is, an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone around its star — Kepler will have to search for much longer than it has so far.

Kepler detects a possible planet by observing the slight dimming of its star's light as the planet passes, or transits, in front. For alien planets with orbits roughly a year long, like Earth's, this transit would occur only once a year, so Kepler would have to watch that star for at least a few years to notice the effect.

Despite the challenge of finding Earth-like worlds, scientists think Kepler is up to the task.

"What we see right now makes me very optimistic that we will find some," Borucki said.

Cosmic census

Kepler's main goal is not just to discover individual planets, but to build up a picture of just how common planets are, the researchers explained.

"What Kepler has found, in fact, is approximately for every two stars we are seeing a planet, or candidate planet," Borucki said. "The number of candidates per star is about 44 percent."

This seeming abundance of planets was far from a foregone conclusion when the mission launched. The first extrasolar planet was discovered in the early 1990s, and the pace of such discoveries has picked up since then, but astronomers are just beginning to get a picture of how widespread alien planets truly are.

To date, astronomers have identified more than 500 alien planets, with Kepler sure to vastly increase that tally once its candidates are confirmed.

"Kepler has identified this bonanza of candidate planets," said Matthew Holman, a Kepler scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "Large numbers of multiple planet systems have been detected."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.