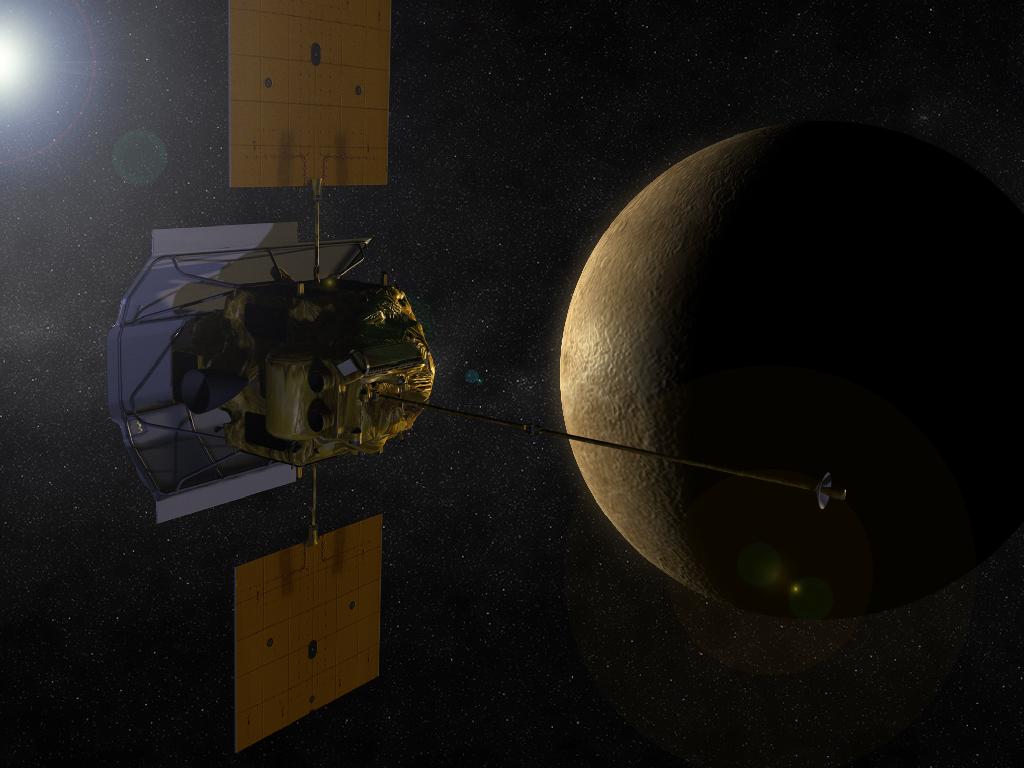

NASA's Messenger probe is set to make history tomorrow night (March 17), when — if all goes well — it will become the first spacecraft ever to enter into orbit around the planet Mercury.

Messenger will map Mercury's surface in detail, as well as investigate the planet's composition, magnetic environment and tenuous atmosphere, among other features.

Here are 10 facts about the $446 million Messenger spacecraft and its yearlong mission that may surprise folks who haven't kept a close eye on the probe since its August 2004 launch:

1. It's a marathon runner

As the innermost planet in the solar system, Mercury isn't all that far away from Earth. On average, Mercury orbits at about 36 million miles (58 million kilometers) from the sun, while Earth circles about 93 million miles (150 million km) from our star.

But on its journey from Earth to Mercury, the Messenger (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging) spacecraft has traveled about 4.9 billion miles (7.9 billion km) – with a "B" – over 6 1/2 years, completing 15 orbits of the sun in the process.

The reason for this circuitous route is twofold: Mercury's proximity to the sun and its lack of an atmosphere. To enter into orbit around Mercury, Messenger needs to slow down dramatically, allowing Mercury's gravity to overcome the tug of the nearby sun and capture the probe.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Spacecraft arriving at orbit around Venus or Mars can slow down by skidding through those planets' relatively substantial atmospheres, a process known as aerobraking. But Messenger can't do that, because Mercury's atmosphere is extremely thin and tenuous.

Since its 2004 launch, Messenger has used multiple flybys of Venus, Earth and Mercury to slow itself down. During these "gravity assist" maneuvers, the planets have bled off enough of Messenger's momentum that the probe is now ready to make one final engine burn and enter into orbit around Mercury. [Photos: New Views of Mercury From Messenger]

2. It's a sprinter, too

Despite its endurance trek, Messenger hasn't exactly been pacing itself. The spacecraft's average speed over its 6 1/2 years in space is about 84,500 mph (136,000 kph) relative to the sun, researchers said.

That's nearly five times as fast as NASA's space shuttles travel when they zip around our planet in low-Earth orbit.

At times, Messenger has rocketed through space at more than 140,000 mph (225,000 kph), approaching the all-time spacecraft speed record. NASA's Helios-2 spacecraft topped 150,000 mph (241,000 kph) relative to the sun back in 1976, researchers said.

3. It's a fuel guzzler

When Messenger launched in 2004, the spacecraft tipped the scales at about 2,420 pounds (1,100 kilograms). About 55 percent of that mass — 1,320 pounds (600 kg) — was propellant.

The primary reason for this huge fuel load is the need to slow down enough to enter orbit around Mercury. Tomorrow night, the spacecraft's main thruster will fire for about 15 minutes, beginning around 8:45 p.m. EDT (0045 GMT on March 18). [Video: Messenger's Mercury Orbit Arrival]

This orbital insertion burn — which will slow Messenger down enough for Mercury's gravity to capture it — will consume about 31 percent of the propellant that the spacecraft carried at launch, researchers said.

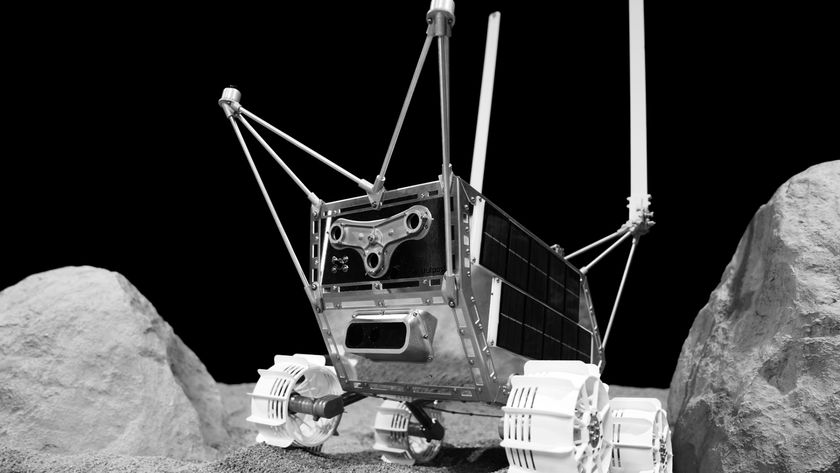

4. Messenger is no giant

The main body of the Messenger spacecraft is 4.7 feet tall by 6.1 feet wide by 4.2 feet deep (1.42 by 1.85 by 1.27 meters) — about the size of a large office desk. Two solar panel "wings," each measuring 5 by 5.5 feet (1.5 by 1.65 m), extend off the sides of the probe.

While Messenger weighed more than a ton at launch, more than half of that load was fuel. The spacecraft's body and scientific instruments weigh about 1,100 pounds (500 kg).

5. It's packed to the gills

Messenger is tasked with helping scientists answer six big questions about Mercury, ranging from why the small planet is so dense to whether or not deposits of water ice may lurk in its polar craters. So the probe is bristling with high-tech gear. [The Enduring Mysteries of Mercury]

Messenger sports seven different science instruments, as well as a radio science experiment. This equipment includes cameras, a laser altimeter, a magnetometer and a variety of spectrometers.

As a result, the spacecraft will be able to do all sorts of things, such as map the planet's entire surface in great detail, gather data on the composition of Mercury's crust and investigate the nature of its magnetic field and wispy atmosphere.

6. Messenger has a parasol

Because Mercury is so close to the sun, spacecraft orbiting the planet must be able to withstand intense heat and solar radiation. One way mission planners fortified Messenger was to give the spacecraft a sun-blocking parasol.

Messenger's heat-resistant, highly reflective sun shade sits on a titanium frame fixed to the front of the spacecraft. The shade measures about 8 feet tall by 6 feet across (2.4 by 1.8 m) and should be extremely efficient, researchers said.

Temperatures on the front of the shade could reach 700 degrees Fahrenheit (371 degrees Celsius) when Mercury is closest to the sun. However, behind the shade, the spacecraft and its instruments will operate at around room temperature — a comfortable 70 degrees Fahrenheit (20 C).

7. A long, looping orbit

Messenger's 12-hour orbit around Mercury will be highly elliptical, bringing the spacecraft within 124 miles (200 km) of the planet's surface at times and sending it as far out as 9,420 miles (15,193 km) away at others.

The brief low-altitude swings will allow the probe to get good looks at Mercury's geological features — and the looping retreats will protect Messenger, ensuring the craft isn't exposed to too much heat reflecting off the scorched planet's desolate surface, researchers said.

8. Messenger following in another probe's footsteps

While Messenger will be the first spacecraft ever to settle into orbit around Mercury, it's not the first probe to study the solar system's innermost planet.

Back in 1974 and 1975, NASA's Mariner 10 spacecraft made three flybys of Mercury, giving scientists their most detailed look at the planet to date. But Mariner 10 saw the same side of Mercury each time, and as a result the probe only mapped about 45 percent of its surface.

Messenger has already filled in most of these mapping gaps on its three Mercury flybys, and the spacecraft will help scientists learn far more about Mercury than the pioneering Mariner 10 was able to teach them more than three decades ago, researchers said.

9. The mission only takes 2 "days"

As ambitious as Messenger's mission is, it will last only two days — two Mercury days, that is. Because Mercury rotates on its axis so slowly, one Mercury day is equivalent to about 176 days here on Earth.

Mercury zips around the sun very quickly, taking just 88 days to complete one orbit. So during Messenger's 12 Earth months of orbital observations, the spacecraft will experience just two Mercury days but more than four Mercury years.

10. It's a kamikaze mission

Messenger's science mission is slated to last one Earth year. The spacecraft's mission could get extended beyond that, researchers have said — but only time will tell.

But however long Messenger eyes Mercury from on high, the probe will be surveying its own final resting place.

Messenger won't have nearly enough fuel to make the return trip to Earth, so when its data-gathering days are done, the spacecraft will eventually spiral down and crash, creating another hole on Mercury's extensively cratered surface.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for complete coverage of Messenger's arrival at Mercury via Twitter @Spacedotcom and Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.