This story was updated at 10:30 p.m. EDT.

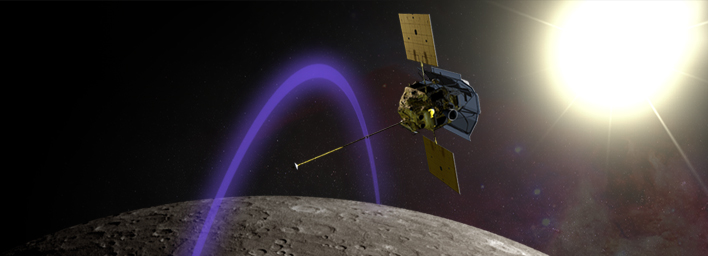

A well-traveled NASA probe made history late Thursday (March 17), becoming the first spacecraft ever to enter into orbit around Mercury.

NASA's Messenger spacecraft fired its main thruster in a 15-minute orbital insertion burn Thursday night to slow down by about 1,900 mph (3,058 kph), enough to enter Mercury's gravitational influence and settle into orbit around the planet.

About an hour after the 8:54 p.m. EDT (0054 GMT) engine burn it was official: Messenger was in a looping, 12-hour orbit around the solar system's innermost planet.

Mercury now has an artificial satellite, for the first time ever.

"This is when the real mission begins," said principal investigator Sean Solomon, Messenger's principal investigator at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, after probe arrived at Mercury. "It's just all coming together and we are really ready to learn about one of Earth's nearest neighbors for the first time."

Applause and handshakes broke out in Messenger's mission operations center at the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory and carried over into a nearby auditorium, where a live webcast of Messenger's Mercury arrival was being broadcast.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The mood is fantastic," said NASA's science missions chief Ed Weiler. The whooping and hollering could be heard through the webcast, and it was not unexpected.

After all, it's not every day an emissary from Earth – even if robotic – takes up station around a planet for the very first time.

"It only happens once in human history, and it's just beginning," Weiler said of humanity's first mission to study Mercury from orbit. "We're going to learn a lot more about Mercury than we've ever seen."

By coincidence, Messenger arrived in orbit around Mercury on St. Patrick's Day, with one commentator suggesting some good luck was in order. The spacecraft will soon begin mapping Mercury and studying the planet's composition, geology and tenuous atmosphere from its orbital perch.

"The spacecraft is ready, and the team is ready," Messenger mission operations manager Andy Calloway, of APL, told reporters before the insertion burn. "On April 4, we'll begin prime science." [Photos of Mercury From Messenger Probe]

A long road to Mercury

Messenger's arrival at Mercury marks the end of a long, circuitous journey for the probe, and the start of its main science operations. The Messenger (Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging) mission first began development about 15 years ago, and the probe launched in August 2004.

Over the past 6 1/2 years, Messenger has been a solar system wanderer, completing 15 orbits of the sun and traveling about 4.9 billion miles (7.9 billion km). During this time, it made one flyby of Earth, two flybys of Venus, and three of Mercury, primarily to slow the probe down in preparation for tonight's orbital insertion maneuver.

Messenger also took pictures and did some science work during these close encounters. Its Mercury observations were the first spacecraft data returned from the planet since NASA's Mariner 10 probe made three flybys in the mid-1970s.

But the Mercury flybys were a prelude to Messenger's chief mission — scrutinizing the planet from orbit for the next 12 months, researchers said.

"The Messenger spacecraft is in orbit around Mercury … we are there," said Eric Finnegan, the mission's systems engineer at APL.

Success wasn't guaranteed

Mission scientists planned for Messenger to slip into a highly eccentric orbit around Mercury. The spacecraft should come as close as 124 miles (200 km) to the planet at times, and retreat to more than 9,300 miles (15,000 km) away at others, researchers said. [Video: Messenger's Mercury Orbit Arrival]

The mission team should begin learning soon — within the next day or so — how well Messenger's actual orbit matches up with the planned one. But just achieving Mercury orbit is a success, and not something to take for granted.

Japan's $300 million Akatsuki probe, for example, failed to enter into Venus orbit in December 2010 when its thrusters conked out early in its insertion burn. Akatsuki is still circling the sun, with another possible shot at Venus coming in late 2016 or early 2017.

Science work begins soon

Over the next 12 months, Messenger will map Mercury's surface in unprecedented detail and investigate the planet's composition, magnetic field, geologic history and thin, tenuous atmosphere, among other features. Scientists hope the probe helps them better understand what makes the tiny planet tick. [Most Enduring Mysteries of Mercury]

"Mercury is a planet where there's many things going on," Solomon said. "What we've learned from the flybys is that all of these things are connected."

The overall goal of Messenger's mission is to use an increased understanding of Mercury to learn more about how our solar system — and solar systems in general — formed and evolved, scientists have said.

Over the next few weeks, the mission team will turn on and check out Messenger's suite of seven science instruments, making sure everything is working properly.

Messenger's first pictures of Mercury from orbit should start trickling out in about two weeks, Solomon said, but the real data flood will come with the official start of the probe's science operations on April 4.

From that point on, Messenger will be beaming home the equivalent of two flybys' worth of information every day, Calloway said.

And while the flybys have given researchers a taste of what to expect, they also fully anticipate some surprises.

"The most exciting stuff will be the stuff we weren't expecting," Weiler said.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.