Spaceships powered primarily by water could open up the solar system to exploration, making flights to Mars and other far-flung locales far cheaper, a recent study has found.

A journey to Mars and back in a water-fueled vehicle could cost as little as one space shuttle launch costs today, researchers said. And the idea is to keep these "space coaches" in orbit between trips, so their relative value would grow over time, as the vehicles reduce the need for expensive one-off missions that launch from Earth.

The water-powered space coach is just a concept at the moment, but it could become a reality soon enough, researchers said. [Video: Space Engines: The New Generation]

"It's really a systems integration challenge," said study lead author Brian McConnell, a software engineer and technology entrepreneur. "The fundamental technology is already there."

Space coach: The basics

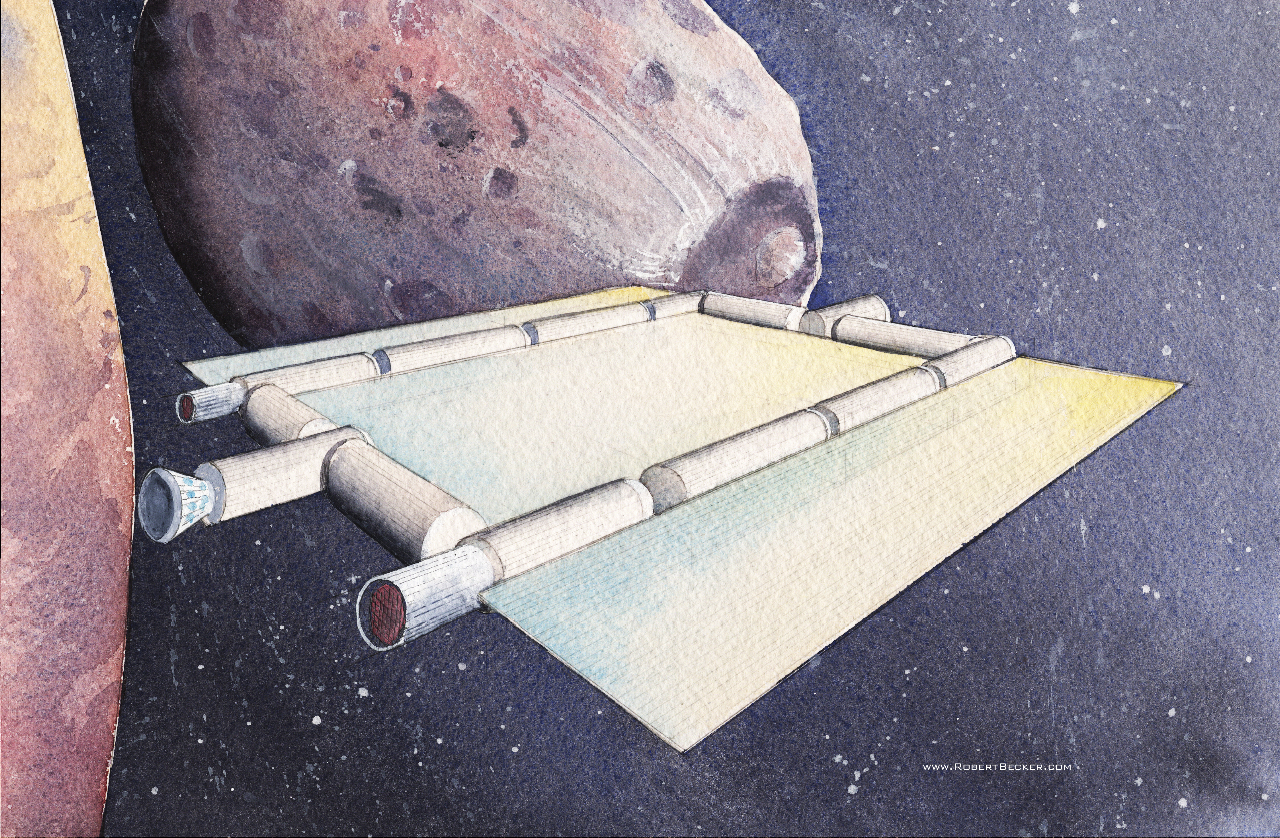

The space coach concept vehicle is water-driven and water-centric, starting with its solar-powered electrothermal engines. These engines would super-heat water, and the resulting steam would then be vented out of a nozzle, producing the necessary amount of thrust.

Electrothermal engines are very efficient, and they're well-suited for sustained, low-thrust space travel, researchers said. This mode of propulsion would do the lion's share of the work, pushing the space coach from Earth orbit to Mars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Smaller chemical rockets could be called into service from time to time when a rapid change in velocity is needed, McConnell said.

The space coach's living quarters would be composed of a series of interconnected habitat modules. These would be expandable and made of fabric, researchers said — much like Bigelow Aerospace's inflatable modules, which have already been deployed and tested in low-Earth orbit.

Water would be a big part of the space coach's body, too, according to the study. Packed along the habitat modules, it would provide good radiation shielding. It could also be incorporated into the fabric walls themselves, freezing into a strong, rigid debris shield when the structure is exposed to the extreme cold of space.

Rotating the craft could also generate artificial gravity approximating that of Earth in certain parts of the ship, researchers said.

Slashing the cost of space travel

The dependence on water as the chief propellant would make the space coach a relatively cheap vehicle to operate, researchers said. That's partly because electrothermal engines are so efficient, and partly because the use of water as fuel makes most of the ship consumable, or recyclable.

Because there are fewer single-use materials, there's much less dead weight. Water first used for radiation shielding, for example, could later be shunted off to the engines. Combined, these factors would translate into huge savings over a more "traditional" spacecraft mission to Mars using chemical rockets, according to the study.

"Altogether, this reduces costs by a factor of 30 times or better," McConnell told SPACE.com. He estimates a roundtrip mission to the Martian moon Phobos, for example, could be made for less than $1 billion.

A space coach journey would also be more comfortable, McConnell added. The ship would carry large quantities of water, so astronauts could conceivably grow some food crops and — luxury of luxuries — even take hot baths now and again.

McConnell and co-author Alexander Tolley published their study last March in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society.

A fleet of space coaches?

McConnell envisions space coaches cruising around the solar system, each individual vehicle fueling up with water in low-Earth orbit when the need arises. In the future, fuel could be sourced along a space coach's travels — for example, water could be mined from an asteroid or a Martian moon.

Parts could be swapped out and upgraded on orbit as well, helping to keep the space coaches in good operating condition for several decades, McConnell said. Each mission undertaken from low-Earth orbit would be far cheaper than anything launching from the ground.

McConnell thinks an entire fleet of space coaches could one day populate the heavens, flying a variety of different flags — as long as somebody takes the initial plunge.

"If one party decides to do this, I think it would spur a lot of other activity," McConnell said. "I think countries wouldn't want to get left behind."

From vision to reality

No huge technological leaps are required to make the space coach a reality, McConnell said. Bigelow's expandable habitats are already space-tested, for example, as are several varieties of electrothermal engine.

"There's not a lot of new technology that needs to be built," McConnell said.

Electrothermal engines that use water as fuel, however, have not been flight-tested, so some work needs to be done on the propulsion system. McConnell envisions holding a design competition for the engines, as well as one for the overall ship design — cash-reward contests that would be like smaller versions of the Google Lunar X Prize, which is a $30 million private race to the moon.

Once winners of these competitions emerge, ground-testing and, eventually, flight-testing would follow. McConnell declined to put forth any specific timelines, but he's optimistic about the possibilities.

"I think things could happen very quickly," he said. "It's really just a matter of convincing decision-makers that this is worth getting into."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.