Why NASA Chose Potentially Threatening Asteroid for New Mission

When it comes to visiting asteroids, NASA doesn't pick run-of-the-mill space rocks. The target of NASA's latest asteroid mission is not only thought to be rich in the building blocks of life, it also has a chance — although a remote one — of threatening Earth in the year 2182.

The asteroid 1999 RQ36 is the target of a new unmanned spacecraft, which NASA plans to launch in 2016 to collect a sample from the space rock and return it to Earth by 2023.

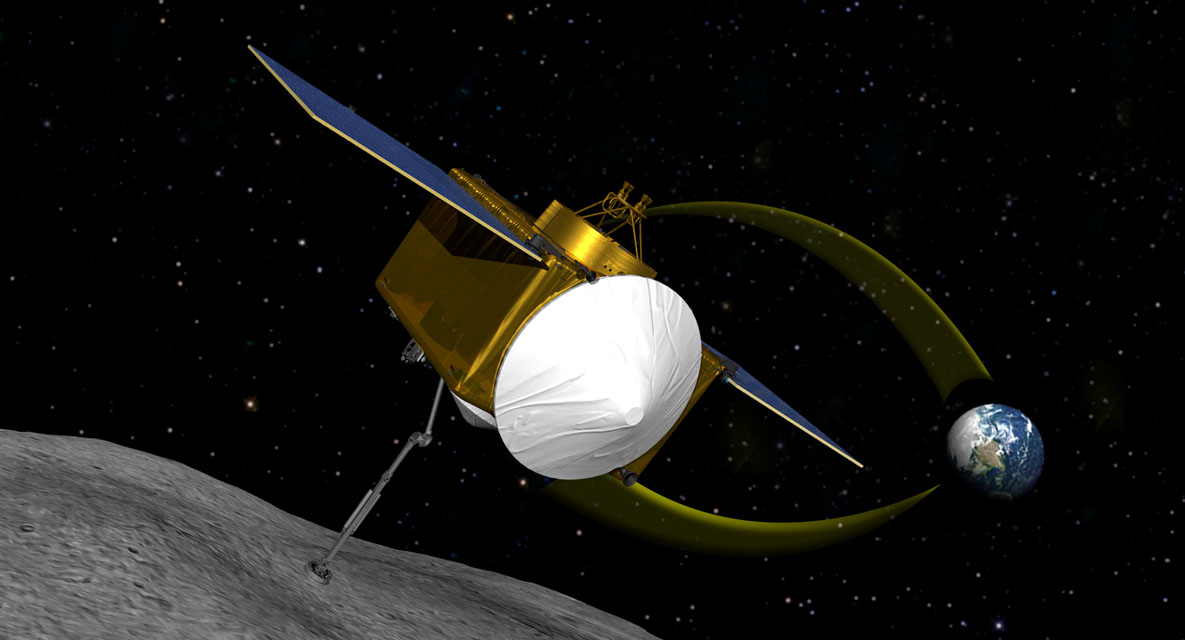

The mission's leaders spent a long time surveying possible destinations for the mission, and finally settled on 1999 RQ36. NASA calls the mission OSIRIS-Rex, which is short for Origins-Spectral Interpretation-Resource Identification-Security-Regolith Explorer.

"We went through a whole series of selection criteria," OSIRIS-Rex's deputy principal investigator Dante Lauretta, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, told SPACE.com. "There are over 500,000 asteroids known. [1999 RQ36] looks really optimum." [Video: The OSIRIS-Rex Mission to 1999 RQ36]

A potentially dangerous asteroid

In addition to digging up clues about our solar system's history, the OSIRIS-Rex mission may be able to help Earth fend off potentially deadly space rocks. That's because asteroid 1999 RQ36 — which is about 1,900 feet (580 meters) wide — is public enemy No. 1 for space rock scientists.

"1999 RQ36 has the highest probability of impacting the Earth of any known Potentially Hazardous Asteroid," according to a mission proposal submitted to NASA by the OSIRIS-Rex in 2009. [Infographic: How NASA's OSIRIS-REx Asteroid Mission Works]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A recent calculation found that the asteroid has a 1-in-1,800 chance of hitting Earth in the year 2170, and a 1-in-1,000 chanceof slamming into us in 2182.

While those are slim odds, they put 1999 RQ36 at the top of the danger list.

"I wouldn't go buy asteroid insurance," Lauretta said. "We're OK for 150 years or so. We're not saving the Earth from immediate danger."

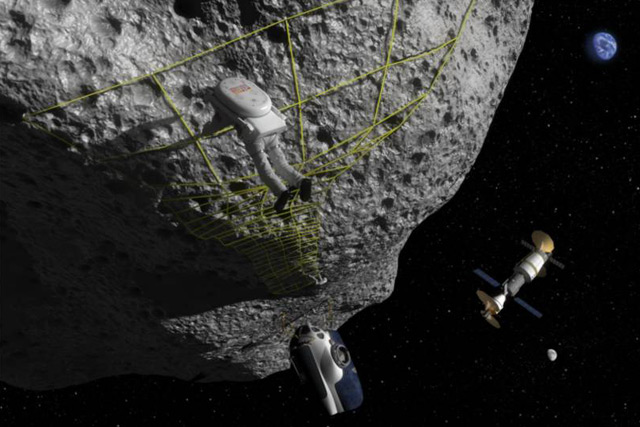

Still, he said studying the asteroid and its orbit up close could help us better predict the risk, and outline a strategy to protect ourselves if necessary. [Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space]

One reason the likelihood of Earth impact can't be better predicted is because scientists don't fully understand the Yarkovsky effect, which causes asteroids to accelerate slightly when they absorb sunlight and then re-emit it as heat.

"[1999 RQ36's] orbit is currently well known because of optical and radar data but the long-term motion is less well understood because of the poorly defined Yarkovsky effect," said Donald Yeomans, manager of NASA's Near-Earth Object Program Office, who is not directly involved with the OSIRIS-Rex mission. "This mission should allow a much better understanding of these effects once the asteroid's size, mass, rotation characteristics and thermal properties are studied."

Target: Asteroid 1999 RQ36

One of the most attractive features of asteroid 1999 RQ36 for scientists is its size: It is as large as five football fields, which means it won't be spinning too fast when OSIRIS-Rex approaches. The asteroid should also have a large supply of lose dirt, or regolith, on its surface for easy sampling.

1999 RQ36 is thought to be carbonaceous, or rich in carbon and organic material, and likely to contain some of the building blocks of life, such as the amino acids used to build the proteins vital to life on Earth.

"We cannot tell from telescopes exactly what kind of material, but we believe it's the sort of stuff that came in through the Earth's atmosphere after liquid oceans first formed, perhaps by 4.45 billion years ago, and provided those building blocks," said OSIRIS-Rex principal investigator Mike Drake of the University of Arizona, during a news conference yesterday (May 25).

In fact, the asteroid is a primitive B-class carbonaceous asteroid, a class that has never been studied up close by a spacecraft before, and should provide an unprecedented opportunity to learn about the history of the solar system and the origin of life on Earth.

The material inside 1999 RQ36 is thought to date to the very formation of our solar system around 4.56 billion years ago. While the space rock now orbits relatively near Earth — making it a convenient target for visiting — scientists think it is a fragment of an even larger asteroid that collided with another rock in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, a few million years ago.

Building on asteroid successes

The OSIRIS-Rex mission is not NASA's first mission to an asteroid, but it will be the first U.S. probe to retrieve samples and return them to Earth. Only Japan's Hayabusa spacecraft, which returned samples of the asteroid Itokawa to Earth in June 2010 after a seven-year journey, has performed a similar feat.

NASA has sent probes to visit asteroids before. The agency's NEAR spacecraft rendezvoused with the asteroid Eros and ultimately touched down on that space rock at the end of its mission in February 2001.

NASA's Dawn probe, meanwhile, is nearing the asteroid Vesta — the second-largest space rock in the asteroid belt. Dawn will orbit Vesta for many months, then head off to visit Ceres, the largest asteroid in the solar system.

But the NEAR and Dawn missions are only visiting asteroids. OSIRIS-Rex will bring pieces back home. And that has scientists brimming with anticipation.

"Asteroid 1999 RQ36 is a perfect target for sample return and I can't wait to see the exciting results from both the in situ science activities and the sample return analysis," Yeomans said.

You can follow SPACE.com Senior Writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Managing editor Tariq Malik contributed to this report. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.