NASA is gearing up for the launch of its new Aquarius observatory, which will help map out the links between Earth's climate and the saltiness of its oceans.

Aquarius is slated to blast off Friday (June 10) at 10:20 a.m. EDT (1420 GMT) atop a Delta 2 rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. NASA had originally scheduled the launch for June 9, but the space agency announced Wednesday evening that it had pushed the liftoff back a day to work out some software issues with the rocket's flight program.

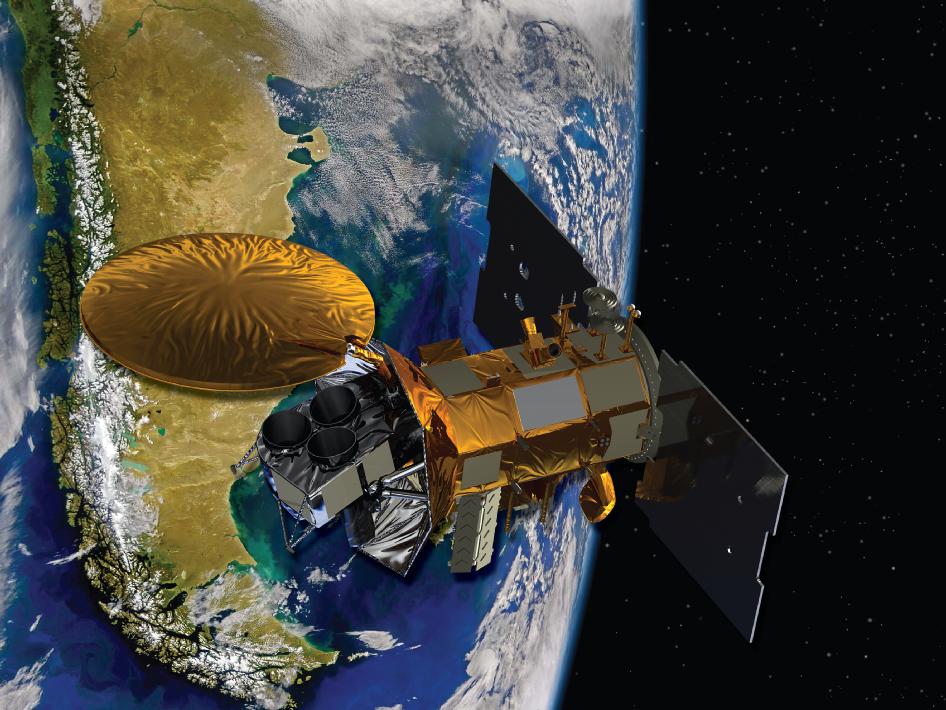

The Aquarius instrument is one of several environment-measuring scientific payloads aboard the SAC-D satellite (Satélite de Aplicaciones Científicas-D), which was built by Argentina's national space agency.

The $287 million Aquarius/SAC-D will join 13 other NASA satellite missions devoted to studying Earth from above. But Aquarius will bring something new to the table, researchers say. Its precise measurements should allow unprecedented insights into global patterns of precipitation, evaporation and ocean circulation — key drivers of our planet's changing climate.

"In order to study these interactions between the global water cycle and the ocean circulation, the piece that we're missing is ocean salinity," Gary Lagerloef, Aquarius principal investigator at Earth and Space Research in Seattle, said in a briefing Tuesday. "And that's the gap that Aquarius is designed to fill." [Video: Sea Salt Changes Ripple Around the World]

Understanding ocean salinity

On average, the world's oceans are 3.5 percent salt. That concentration doesn't vary much; extremes range from 3.2 percent to 3.7 percent at various spots around the globe, Lagerloef said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, even such subtle differences can have big impacts. Salinity levels strongly influence ocean temperatures and circulation patterns, which themselves affect the exchange of water and heat between the oceans and Earth's atmosphere.

So measuring ocean salinity precisely is important to better understand and predict Earth's climate, researchers said.

"Aquarius, and successor missions based on it, will give us, over time, critical data that will be used by models that study how Earth's oceans and atmosphere interact, to see trends in climate," Lagerloef said in a statement. "The advances this mission will enable make this an exciting time in climate research."

Until now, most ocean salinity measurements have been taken from ships and buoys. Such readings tend to be sparse and patchy; some regions of the globe, including the southern oceans, receive very little attention.

"What the satellite does is give you a systematic measurement over the whole globe," Lagerloef said.

Aquarius is expected to take measurements for at least three years. Its readings will complement and extend the efforts of the European Space Agency's Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) mission, which launched in November 2009.

Sniffing salt from above

Shortly after liftoff, the Aquarius/SAC-D spacecraft is to settle into orbit 408 miles (657 kilometers) above Earth. Researchers will monitor the satellite's behavior for 25 days, to make sure everything is working properly. Then they'll begin to ready Aquarius for measurement-taking.

"It's worth the wait, to check it out completely," said Amit Sen, the Aquarius project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

When it's up and running, Aquarius will use a set of three precise radiometers to measure microwave emissions coming from the ocean surface. Certain characteristics of these emissions are affected by salinity, so analyzing the readings will reveal just how salty the observed patch of ocean is.

Aquarius also boasts a scatterometer, which will use radar to measure waves at the ocean surface. Rough seas can create "noise" that confuses or degrades the salinity signal; the scatterometer will help researchers correct for this impact.

As Aquarius zips around the Earth every 90 minutes, it will take continuous salinity readings in a swath about 250 miles (400 km) wide, creating a global salinity map every seven days. It will be able to detect salinity differences as small as 0.02 percent. That's the equivalent of an eighth of a teaspoon of salt in a gallon of water, researchers say. [The World's Biggest Oceans and Seas]

Launch outlook looks good

Assuming NASA fixes the software bug, the outlook for a Friday launch is good. The weather should cooperate; NASA currently pegs the chances of a launch-delaying weather violation at 0 percent.

Aquarius/SAC-D is blasting into space aboard a Delta 2 rocket operated by the firm United Launch Alliance (ULA).

NASA recently lost two other Earth-observing satellites, the Orbiting Carbon Observatory and the Glory spacecraft, to problems during launches provided by Virginia-based Orbital Sciences Corp. However, NASA officials said those failures played no part in using ULA for the Aquarius/SAC-D launch. The decision to go with the Delta 2 was made eight or nine years ago, Sen said.

Aquarius is one of eight instruments aboard the spacecraft. The other equipment will observe fires and volcanoes, map sea ice and collect a wide range of other environmental data.

The mission is a collaboration between NASA and the Comision Nacional de Actividades Espaciales (CONAE), Argentina's space agency. The project also involves the participation of Brazil, Canada, France and Italy.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site of SPACE.com. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.