NASA Spacecraft Discovers 122 Pairs of Star Twins

Two NASA satellites built to study the sun have discovered 122 previously unknown sets of twin stars, scientists say.

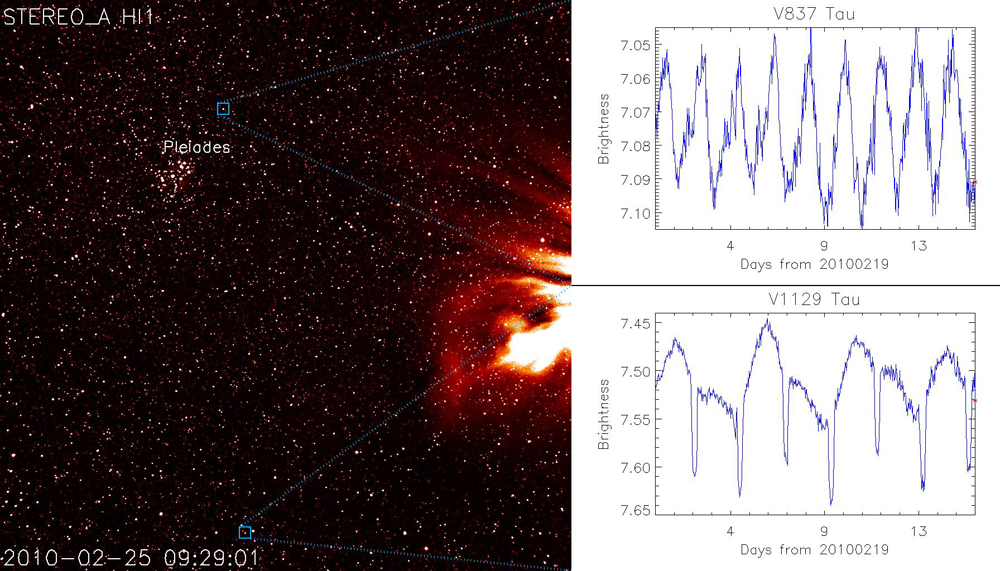

A team from the United Kingdom used NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or Stereo, to spot the paired stars. The Stereo observatories noticed the dimming that occurs when one of the stars passes in front of the other, as seen from Earth

Since their launch in 2006, the two nearly identical Stereo spacecraft have snapped images of almost 900,000 background stars. Both satellites contain two heliospheric imagers, which record eruptions from the sun. But they also gather information about the stars that routinely pass through the instruments' field of view. [Video: NASA’s STEREO Planet-Finders]

"We've used the stars to calibrate the instruments," researcher Danielle Bewsher of the University of Central Lancashire told SPACE.com in an email interview. "Because our calibration has been made to a high standard, [we] knew that we could subsequently do science with the background stars."

Studying the sun, and other stars

Stereo's imagers don't study the sun directly. Instead, they point slightly to the right of it, keeping our star's powerful rays out of the sensitive cameras' field of view. The same instruments that gather precise data on solar eruptions known as coronal mass ejections also register minute changes in brightness from the stars shining in the background.

Stereo is composed of two observatories following Earth's path through space; one travels in front of our planet, while the other trails behind it. The team used data from the Ahead spacecraft, which orbits about 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) in front of the Earth. [Amazing New Sun Photos from Space]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition to finding more than 100 new eclipsing binaries, the team also gathered data on 141 previously identified pairs.

Binary stars abound in the galaxy. But eclipsing binaries are relatively hard to find, because in order to observe one star passing in front of the other, the two must be in a direct line of sight from the point of observation.

The previously undiscovered eclipsing binaries don't tend to have a large change in brightness, Bewsher said. This suggests that the reason they weren't found earlier was because previous instruments just weren't sensitive enough.

Because of the interaction of one star on another, "eclipsing binaries allow for more detailed studies of their host stars," said Bewsher. "A catalogue of bright EBs amenable to follow-up observations would therefore be very useful to a wide range of astronomers."

Planets, too?

In addition to searching for pairs of stars, the U.K. team hoped to locate a few alien planets as well. Specifically, they looked for transiting planets — bodies that, like eclipsing binaries, pass between their parent star and the Earth. The slight dimming in brightness caused by the planets' passage can reveal their presence.

"The analysis would have been most sensitive to a transiting exoplanet with a period of less than about 6.5 days," Bewsher said.

This is because each star only stays in the frame of STEREO's imagers for 19.44 days.

The only candidate found by the team was determined to be too large and too massive to be a planet. Instead, it seems to be a brown dwarf, a failed star with a mass between that of giant planets and small stars. Follow-up measurements are in progress to verify its identity.

Most of the team's data comes from only one of the imagers on the STEREO Ahead observatory. The field of the second imager covers much of the satellite's path, affecting signal detection.

The team has been working steadily on analyzing the captured images stored in the camera, as well as developing tools to work with the information gleaned by the second orbiter. The forthcoming data should reveal a similar wealth of new information, researchers said.

The team presented some initial results in April at the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting in Wales. They will be detailed in an upcoming issue of the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd

Most Popular