Black Hole Caught in Act of Swallowing Star

For the first time, a black hole has been caught in the act of tearing apart and swallowing a star that got too close.

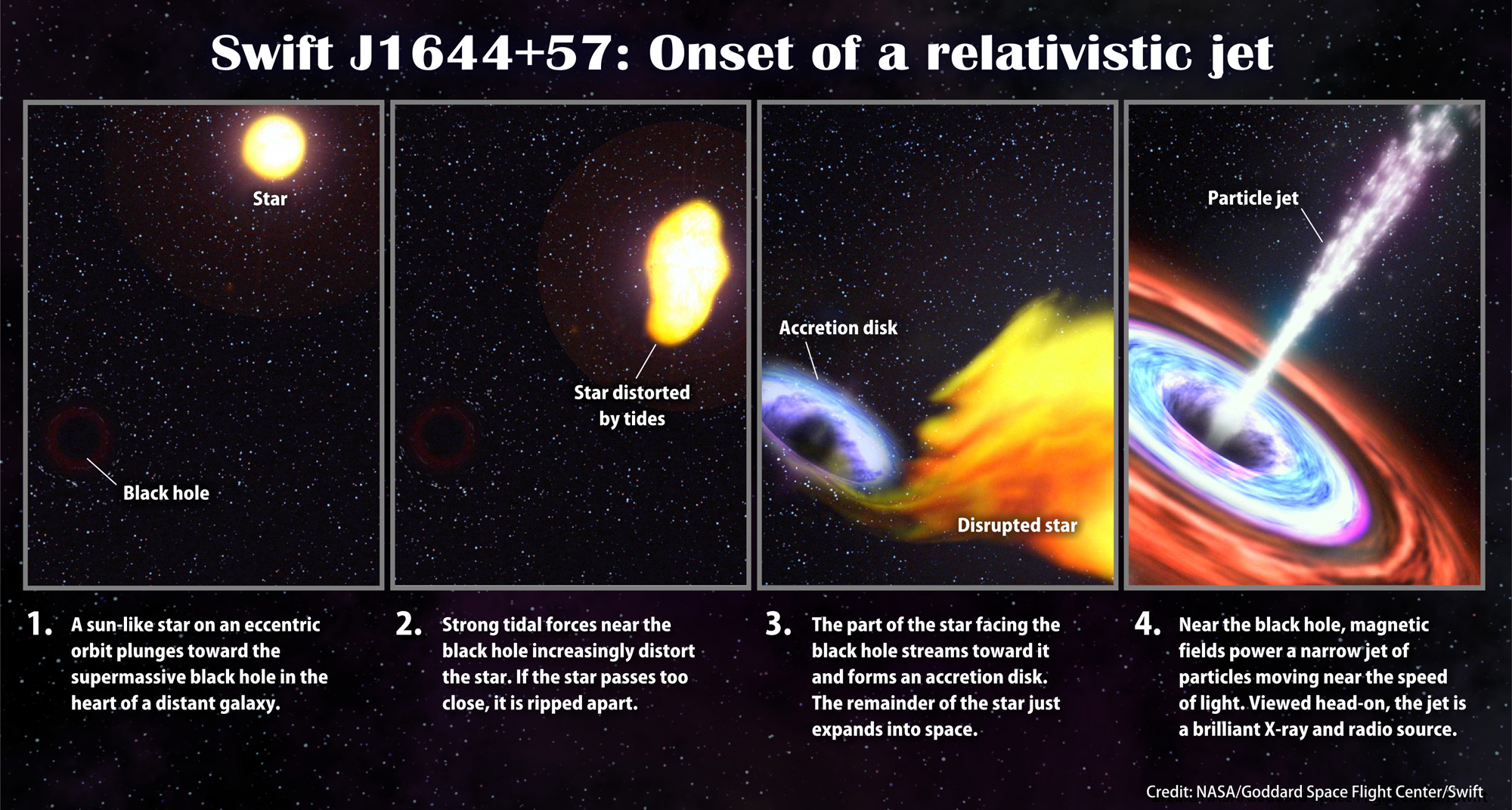

Scientists, who until now had witnessed only the aftermath of such events, say the observation is shedding light on "relativistic jets," bursts of matter that shoot out at nearly the speed of light.

At the centers of virtually all large galaxies are supermassive black holes. These monsters, which are millions to billions of times the mass of the sun, can rip apart passers-by, gravitationally pulling at stars in gigantic versions of how our moon tugs on Earth's oceans to generate tides. [Photos of the star-eating black hole]

Evidence for this destruction may come in the form of a bright flare of ultraviolet, gamma and X-rays, a flare that can theoretically last for years as the star is gradually consumed. Although scientists have observed the aftermath of such "tidal disruption" events several times, they had never seen the onset of one.

"Now we've seen the start of this event for the first time," study co-author David Burrows, an astrophysicist at Pennsylvania State University, told SPACE.com.

The Swift satellite observed a string of extremely bright bursts of gamma rays from outside our galaxy that began March 25 and lasted about two days. Scientists have detected gamma ray bursts in the past, but this pattern of light was completely different. [Photos: Black Holes of the Universe]

"It was nothing like we expected for a gamma-ray burst," said Ashley Zauderer, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who co-authored a different study on the event.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

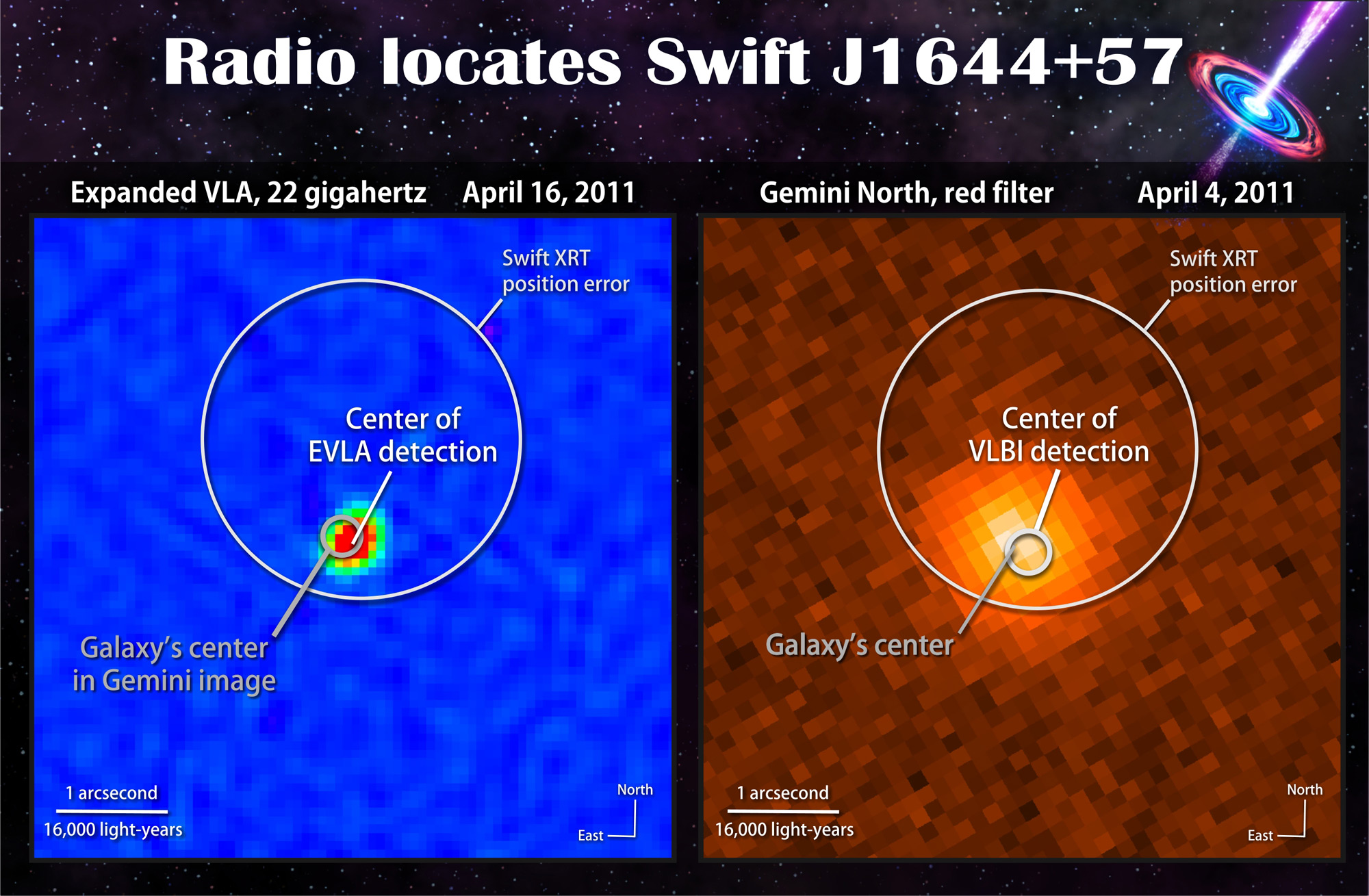

Additional observations by several radio telescopes suggested the flare occurred in the center of a galaxy, and that the source of this radiation was expanding at 99.5 percent the speed of light. This suggested the flare came from a relativistic jet released after a black hole ripped apart a star, which scientists named Swift J1644+57.

Based on the wavelengths of light emitted by the flare and the way it evolved over time, the scientists concluded that it originated from matter falling or accreting onto a black hole about 1 million times the mass of the sun, comparable to the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way.

In the past, scientists had missed the fact that relativistic jets could form as black holes ripped apart stars. This helps explain why the flare had X-rays 10,000 times brighter than predicted for a tidal disruption event: Basically, relativistic jets are focused bursts of energy.

"It's not surprising that such an event would cause jets, but it was just never discussed in past publications," Burrows said.

Future research could reveal more outbursts of this kind. Knowing how often these occur will help scientists figure out just how many galaxies harbor supermassive black holes, what the properties of these monsters are, the density of stars in galactic cores, and how these jets form.

"There are a lot more surprises in space for us to discover, especially as we continue to make huge strides in the technical capabilities of our instruments," Zauderer told SPACE.com.

The scientists detailed their findings in two papers in the Aug. 25 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us