Milky Way Owes Its Shape to Crashes With Dwarf Galaxy

Two collisions with a dwarf galaxy over the last nearly 2 billion years may have been the cause of the Milky Way's spiral arm structure, scientists say.

The new findings hint that impacts with even relatively small galaxies have played an important role in shaping galactic structure throughout the universe, researchers said.

In trying to explain the shape of our own galaxy, the Milky Way, with its prominent spiral arms rooted in a central bar, scientists have traditionally dismissed the influence of outside forces, even though astronomers have seen shape-changing mergers of other galaxies.

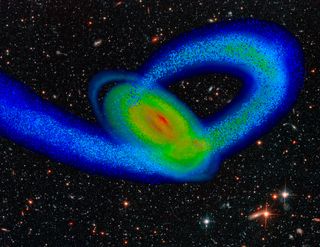

For their study, scientists focused on the nearby Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, much of which had been ripped apart by the gravitational pull of the Milky Way, leaving debris that forms a huge but very faint stream of stars around our galaxy. Altogether, this dwarf galaxy might have once been far more substantial, maybe 100 times more massive. [Photos of Great Galaxy Collisions]

"Sagittarius was among the largest of the Milky Way's dwarf satellites before it began to be torn apart by galactic tides, but objects on that scale are still relatively small details in the eyes of many galaxy-formation theorists," said study lead author Chris Purcell, an astrophysicist at the University of Pittsburgh."It had always been assumed that the Milky Way had evolved relatively unperturbed over the past few billion years in terms of its global structure and appearance."

However, in computer simulations, Purcell and his colleagues found this dwarf galaxy's collision with the Milky Way might have had dramatic consequences. It may have triggered the formation of our galaxy's spiral arms, caused the flaring seen in the outermost disk, and influenced the growth of its central bar.

Their models also could have generated ringlike structures wrapping around the Milky Way, similar to ones actually seen in our galaxy, such as the Monoceros ring.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers have seen mergers of galaxies with smaller companions, known as minor mergers, and mergers of galaxies of equal mass, so-called major mergers. Minor mergers such as that of the Milky Way and the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy are expected to be far more common than major mergers.

"We may well learn to generally view intermediate-scale spirality in systems like the Milky Way as transient symptoms of recent impacts involving satellites too faint to see," Purcell told SPACE.com. "Future observations of nearby galaxies may even begin to discern the brightest of such companions, which will help solidify the phenomenological link between minor mergers and spiral arms."

The scientists are detailed in the Sept. 15 issue of the journal Nature.

Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us