Saturn's Moon Titan May be More Earth-Like Than Thought

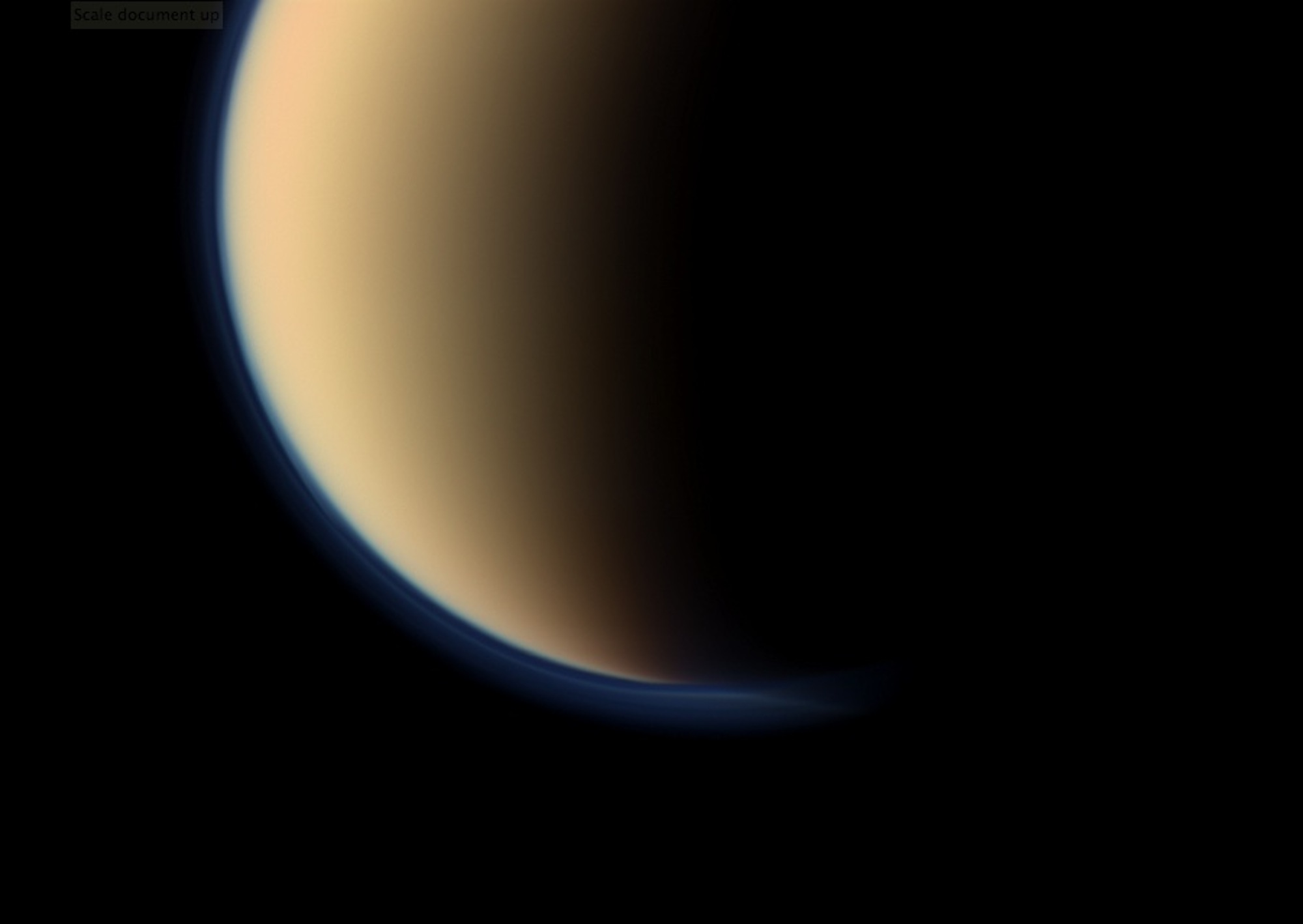

Saturn's moon Titan may be more similar to an Earth-like world than previously thought, possessing a layered atmosphere just like our planet, researchers said.

Titan is Saturn's largest moon, and is the only moon known to have a dense atmosphere. A better understanding of how its hazy, soupy atmosphere works could shed light on similar ones scientists might find on alien planets and moons. However, conflicting details about how Titan's atmosphere is structured have emerged over the years.

The lowest layer of any atmosphere, known as its boundary layer, is most influenced by a planet or moon's surface. It in turn most influences the surface with clouds and winds, as well as by sculpting dunes.

"This layer is very important for the climate and weather — we live in the terrestrial boundary layer," said study lead author Benjamin Charnay, a planetary scientist at France's National Center of Scientific Research.

Earth's boundary layer, which is between 1,650 feet and 1.8 miles (500 meters and 3 kilometers) thick, is controlled largely by solar heat warming the planet's surface. Since Titan is much further away from the sun, its boundary layer might behave quite differently, but much remains uncertain about it — Titan's atmosphere is thick and opaque, confusing what we know about its lower layers. [Amazing Photos of Titan]

For instance, while the Voyager 1 spacecraft suggested Titan's boundary layer was about 2 miles (3.5 km) thick, the Huygens probe that plunged through Titan's atmosphere saw it as only about 1,000 feet (300 m) thick.

To help solve these mysteries about Titan's atmosphere, scientists developed a 3D climate model of how it might respond to solar heat over time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The most important implication of these findings is that Titan appears closer to an Earth-like world than once believed," Charnay told SPACE.com.

Their simulations revealed the lower atmosphere of Titan appears separated into two layers that are both distinct from the upper atmosphere in terms of temperature. The lowermost boundary layer is shallow, only about 2,600 feet (800 meters) deep and, like Earth's, changes on a daily basis. The layer above, which is 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) deep, changes seasonally.

The existence of two lower atmospheric layers that both respond to changes in temperature help reconcile the formerly disparate findings regarding Titan's boundary layer, "so there are no more conflicting observations," Charnay said.

This new work help explains the winds on Titan measured by the Huygens probe, as well as the spacing seen between the giant dunes on Titan's equator. Also, "it could imply the formation of boundary layer clouds of methane on Titan," Charnay said. Such clouds were apparently seen before but not explained.

In the future, Charnay and his colleagues will include how methane on Titan moves in a cycle from surface lakes and seas to atmospheric clouds, just as water does on Earth.

"3D models will be very useful in the future to explain the data we will get about the atmospheres of exoplanets," Charnay said.

Charnay and his colleague Sébastien Lebonnois detailed their findings in the Jan. 15 issue of the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us