Habitable Zones Around Alien Suns May Depend on Chemistry

Trace elements in stars may influence the evolution of habitable zones around them where life as we know it might dwell, scientists now find.

Stars are made nearly entirely from hydrogen and helium gas. Still, traces of heavier elements — which astronomers call metals, even if they are not what one normally think of as metals — can be found in stars as well, either inherited from the remains of older stars or forged via nuclear fusion.

Scientists can detect what elements a star possesses by looking at its light, which comes in a wide variety of wavelengths, some visible, many invisible. The wavelengths of light that matter emits often comes in specific clumps or lines, which can act like a fingerprint, revealing the identity of the material in question.

By looking at the wavelengths or spectra of light from nearby dwarf stars as part of searches for alien worlds, or exoplanets, researchers have with high precision determined the abundance of certain elements for more than a hundred of these stars, with more to come. Now researchers suggest variations in the compositions of these stars could impact the habitable zones around them.

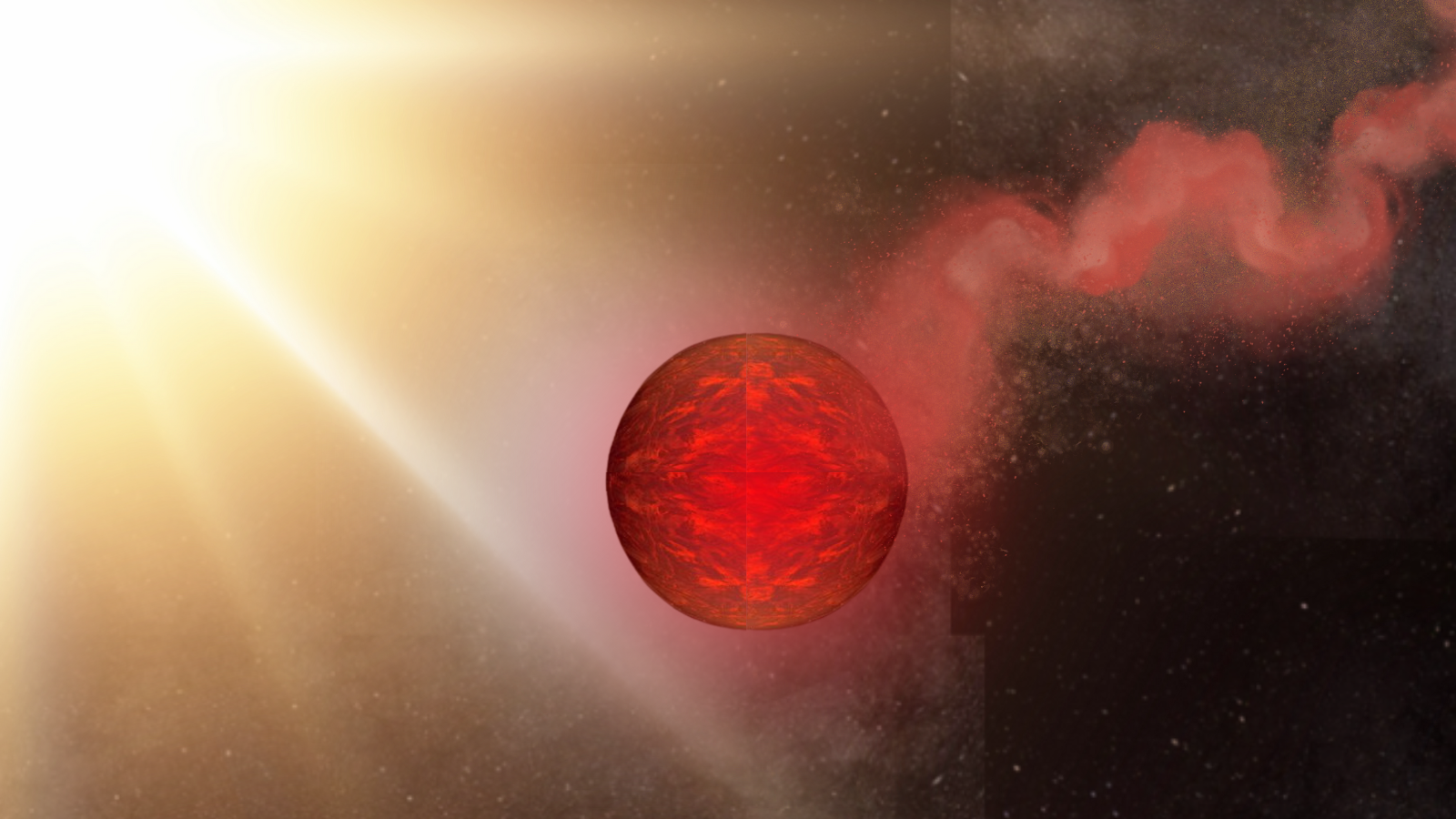

What scientists call the habitable zone of a star is defined by whether liquid water can survive on a planet's surface, given that life exists virtually wherever there is liquid water on Earth. Too far from a star, and the lack of light makes a world too cold, freezing all its water; too close to a star, and all that blazing heat makes a world too hot, with its water eventually all boiling off. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets ]

Finding the habitable zone

Normally scientists figure out the habitable zones of stars by seeing how hot the stars are. This involves looking at their brightness and color. Computer models now suggest that variations in a star's elemental composition might alter its long-term behavior, significantly affecting the location and lifetime of its habitable zone.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I was expecting some subtle changes in our stellar evolution models in terms of the surface temperature and brightness — I was not looking for such a dramatic change in the lifetimes of the stars," said study lead author Patrick Young, a theoretical astrophysicist and astrobiologist at Arizona State University.

Scientists typically measure the abundance of heavy elements in a star relative to the iron content in its atmosphere, as iron is a common element and its spectrum is relatively easy to measure. Past research found that abundances of various heavy elements could vary by more than a factor of two given otherwise similar star types. [Video: Kepler Reveals Lots of Planets: Some Habitable?]

Young and his colleagues generated computer models for how variations in levels of eight elements — carbon, oxygen, sodium, aluminum, magnesium, silicon, calcium and titanium — might affect the behavior of F, G and K stars, those most similar to our sun. Metals in a star can alter its evolution by affecting how opaque its plasma is.

"The persistence of stars as stable objects relies on the heating of plasma in the star by nuclear fusion to produce pressure that counteracts the inward force of gravity," Young explained. "A higher opacity traps the energy of fusion more efficiently and results in a larger radius, cooler star. More efficient use of energy also means that nuclear burning can proceed more slowly, resulting in a longer lifetime for the star."

Elements of stars

The scientists found that calcium, sodium, magnesium, aluminum and silicon had small but significant effects on a star's evolution. Higher levels of these elements resulted in cooler, redder stars.

Oxygen also proved especially important because it could dramatically alter the lifetime of a star's habitable zone.

"The habitable lifetime of an orbit the size of Earth's around a one-solar-mass star is only 3.5 billion years for oxygen-depleted compositions but 8.5 billion years for oxygen-rich stars," Young said. "For comparison, we expect the Earth to remain habitable for another billion years or so, for about 5.5 billion years total, before the sun becomes too luminous. Complex life on Earth arose some 3.9 billion years after its formation, so if Earth is at all representative, low-oxygen stars are perhaps less than ideal targets."

Moreover, the presence of oxygen was linked with ultraviolet radiation, which is known to damage cells. "A star that is otherwise like the sun in iron abundance and mass but relatively scarce in oxygen could produce twice as much of the cell-damaging radiation that causes skin cancer and is sometimes used for sterilization," Young said.

Young did note that habitable zones are a rather nebulous concept, since they depend on the atmosphere and geological evolution of a planet, making it tricky to draw any conclusions about the lifetime or extent of habitable zones.

"This is why we concentrate on the stellar modeling," Young said. "We can provide input to any climate model other researchers wish to use. For illustrative purposes we have chosen a simple, conservative prescription, not too optimistic or pessimistic."

Pinning down alien planets

A better knowledge of where a star's habitable zone really lies could influence which exoplanets astrobiologists end up studying more and which they end up ignoring because they lie outside habitable zones.

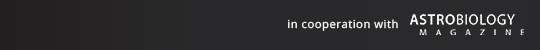

"Kepler has already detected worlds in the current habitable zones of their stars and planets smaller than Earth, and there are dozens more candidates that await confirmation," Young said. "Detecting a planet with life will be a difficult proposition at best, requiring too many resources to observe indiscriminately. With this information we can narrow down our search to planets that are not only currently in their habitable zones, but have been and will remain there for long enough to potentially develop complex life."

The composition of a star can also influence the composition of its planets. Two important considerations are the carbon-oxygen and magnesium-silicon ratios of stars, which can affect whether a planet has certain magnesium- or silicon-loaded clay minerals such as magnesium silicate (MgSiO3), silicon dioxide (SiO2), magnesium orthosilicate (Mg2SiO4), and magnesium oxide (MgO). Clay minerals seem to be a good surface to create key components of life, such as the lipid membranes of cells.

"This is why one of the targets of the Mars Science Laboratory will be phyllosilicate clays in Gale Crater," Young said. "Some clays are better than others, and the magnesium-silicon ratio in part determines the type of clay formed."

Variety of cosmic elements

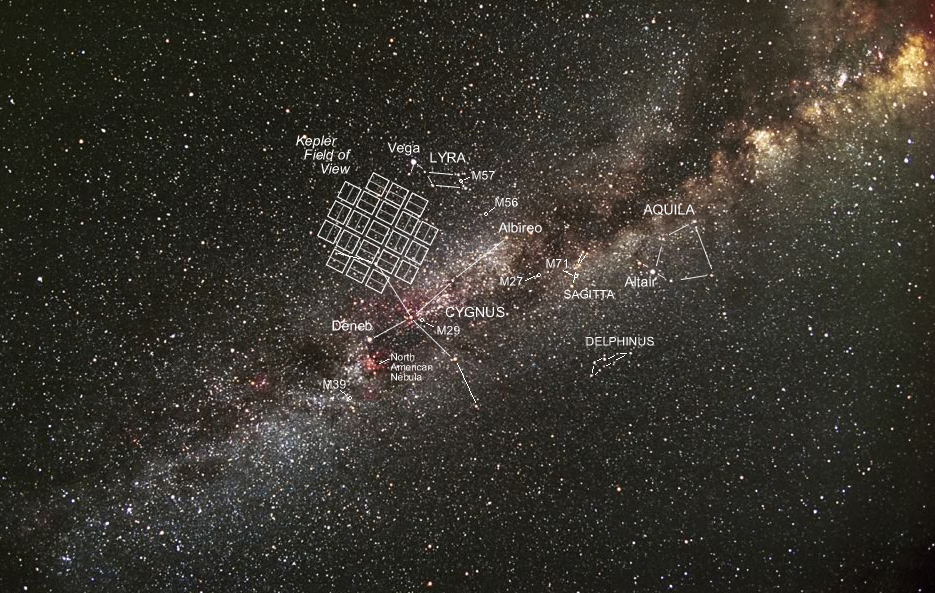

Variations in the compositions of stars could also lead to planets that have different elemental combinations dominating, such as a planet with mostly carbon-based rock as opposed to our silicon-based Earth. "We'd expect tectonics and volcanism to be very different on a planet whose crust is dominated by graphite and silicon carbide than on Earth."

Certain elements within a star also strongly line up with the abundance of radioactive elements such as uranium and thorium, which are key in determining how molten the interior of planets are, Young said. Molten planetary interiors are key to plate tectonics, which in turn may be important to the evolution of life on Earth.

Young noted that some of the elements they would like to look at are very difficult to observe. For instance, "we want to find trace elements that are important to terrestrial-style life like molybdenum and phosphorus," he said. "I am conducting other research to find abundant elements that we could use as proxies for finding enhancements in those trace elements because they are produced in the same conditions inside stars or stellar explosions."

The researchers are now analyzing the elemental abundances seen in 600 stars that are targets of exoplanet searches. They are also producing a much larger set of stellar evolution models for different mass stars and compositions.

"We will be producing a list of what we consider the best 100 targets for habitable planet searches based on a number of criteria including those presented in this work," Young said.

Young and his colleagues detailed their findings Jan. 11 at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us