Hidden Galaxies May Swarm Near Our Own Milky Way

Tantalizing hints of tiny, hard-to-see galaxies on the outskirts of our cosmic neighborhood may help astronomers solve a longstanding mystery.

Researchers recently reported dozens of candidate objects that could represent missing dwarf galaxies predicted by theory, but generally hidden from sight. One particularly promising gas ball shows signs of being a lost satellite of the Milky Way, scientists say.

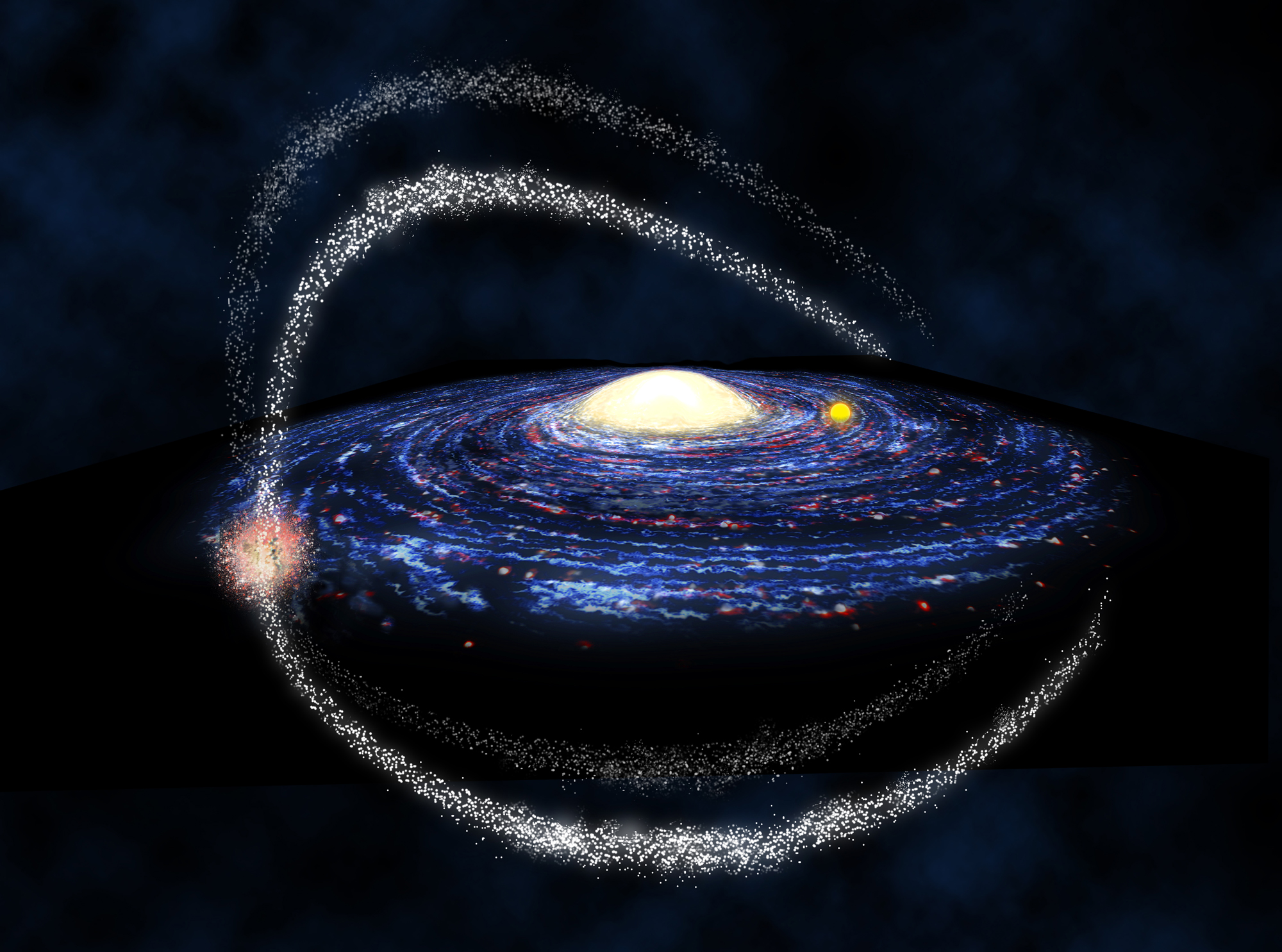

The theory of dark matter — i.e. that much of the universe is made of invisible stuff that only interacts with normal matter via gravity — predicts that thousands of miniature clumps of dark matter should be orbiting our Milky Way galaxy and its neighbor, Andromeda. Many of these clumps should have also attracted gas to form stars that shine in visible light.

Yet of the thousands of dwarf galaxies predicted by theory, only 60 have been detected.

"The discrepancy between what these cold dark-matter models show and the observations show in terms of the number of low-mass galaxies — that's called the missing satellites problem," said Jana Grcevich, an astronomy graduate student at Columbia University. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy]

Chipping away at the mystery

Over the last decade, astronomers have been chipping away at the missing satellites problem.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Of the 60 known local mini-galaxies, about half were found fairly recently. These have been uncovered by scouring observations from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which maps large swaths of the sky, for stars with the right colors and properties to belong to their own distinct groups outside the main body of the Milky Way.

But Grcevich and her colleagues have taken a new tack. Instead of looking for stars, which may be too far away to see in this survey, the astronomers looked for gas.

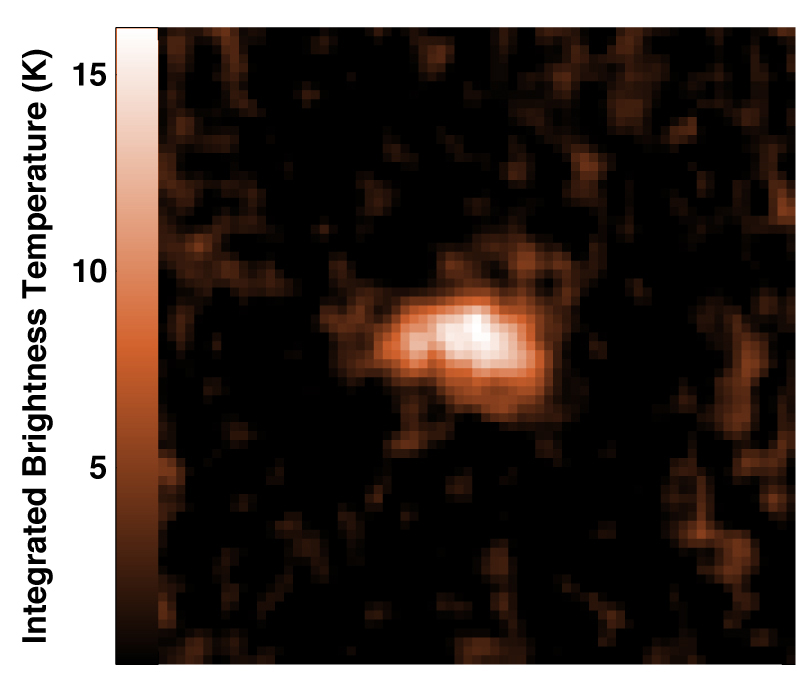

The researchers analyzed the Galactic Arecibo L-Band Feed Array HI (GALFA-HI) survey, which searches for neutral hydrogen gas across the sky. They used an automated algorithm to pick out discrete clouds of gas, and applied a filtering technique to subtract out much of the gas from the Milky Way in the foreground.

This process left about 2,000 clouds.

"Out of that haystack, I'm trying to pick out the ones that are most like local dwarf galaxies," Grcevich told SPACE.com.

At the end, Grcevich was left with 54 candidate objects that appear to be small bundles of gas beyond the main body of the Milky Way galaxy that could represent more of its hidden dwarf galaxy neighbors.

Grcevich presented her findings in January at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

Awaiting confirmation

To confirm whether any of these 54 candidates really are missing satellite galaxies, the researchers need follow-up observations that go deeper and look for fainter signs than the all-sky surveys. In fact, Grcevich already has some time reserved on the MDM Observatory at Arizona's Kitt Peak at the end of February. Some of these observations may be able to sight stars that would confirm the galaxies' existence.

Until then, the scientists have been able to perform some other checks.

About 10 of the gas clouds spotted in the study are in areas also observed by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Though initial analysis of these data didn't show any noticeable star populations at these sites, it's possible that they are so faint they were missed.

And indeed, the location of one of Grcevich's candidate gas clouds does seem to contain a set of stars that may have the right colors and properties to be a distant dwarf galaxy.

"You see something that looks an awful lot like the feature you would expect from the type of stellar population you would predict in a Local Group dwarf galaxy," Grcevich said. "That's really hinting that something's going on at that position."

The astronomers hope to soon know for sure whether this ball of gas, and the other candidates uncovered, really are more of the missing satellites.

If they are, not only will they help resolve the mystery, but they could shine some light on the issue of dark matter itself, which scientists still have never detected directly, and struggle to understand.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.