Billions of Habitable Alien Planets Should Exist in Our Galaxy

There should be billions of habitable, rocky planets around the faint red stars of our Milky Way galaxy, a new study suggests.

Though these alien planets are difficult to detect, and only a few have been discovered so far, they should be ubiquitous, scientists say. And some of them could be good candidates to host extraterrestrial life.

The findings are based on a survey of 102 stars in a class called red dwarfs, which are fainter, cooler, less massive and longer-lived than the sun, and are thought to make up about 80 percent of the stars in our galaxy.

Finding super-Earths

Using the HARPS spectrograph on the 3.6-metre telescope at the European Southern Observatory's La Silla Observatory in Chile, astronomers found nine planets slightly larger than Earth over a six-year period. These planets, called super-Earths, weigh between one and 10 times the mass of our own world, and two of the nine were discovered in the habitable zone of their parent star, where temperatures are right for liquid water to exist.

Extrapolating from these findings, the researchers estimate that tens of billions of these planets are to be found in the Milky Way, and about 100 should lie in the immediate neighborhood of the sun. [Vote Now! Strangest Alien Planet Finds]

"Our new observations with HARPS mean that about 40 percent of all red dwarf stars have a super-Earth orbiting in the habitable zone where liquid water can exist on the surface of the planet," team leader Xavier Bonfils of the Observatoire des Sciences de l'Univers de Grenoble in France said in a statement. "Because red dwarfs are so common — there are about 160 billion of them in the Milky Way — this leads us to the astonishing result that there are tens of billions of these planets in our galaxy alone."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The two stars found inside the habitable zone were discovered around the stars Gliese 581 and Gliese 667 C. The latter planet is the second of three worlds orbiting its star, and seems to lie right in the middle of Gliese 667 C's habitable zone. Although the planet has four times the mass of Earth, it is considered the closest twin to Earth found so far.

Search for life

This and other planets are good candidates for follow-up studies that aim to analyze the atmospheres of these worlds for signs that organisms are living there.

"Now that we know that there are many super-Earths around nearby red dwarfs, we need to identify more of them using both HARPS and future instruments," said team member Xavier Delfosse. "Some of these planets are expected to pass in front of their parent star as they orbit — this will open up the exciting possibility of studying the planet's atmosphere and searching for signs of life."

However, there are some issues with looking for life around red dwarfs.

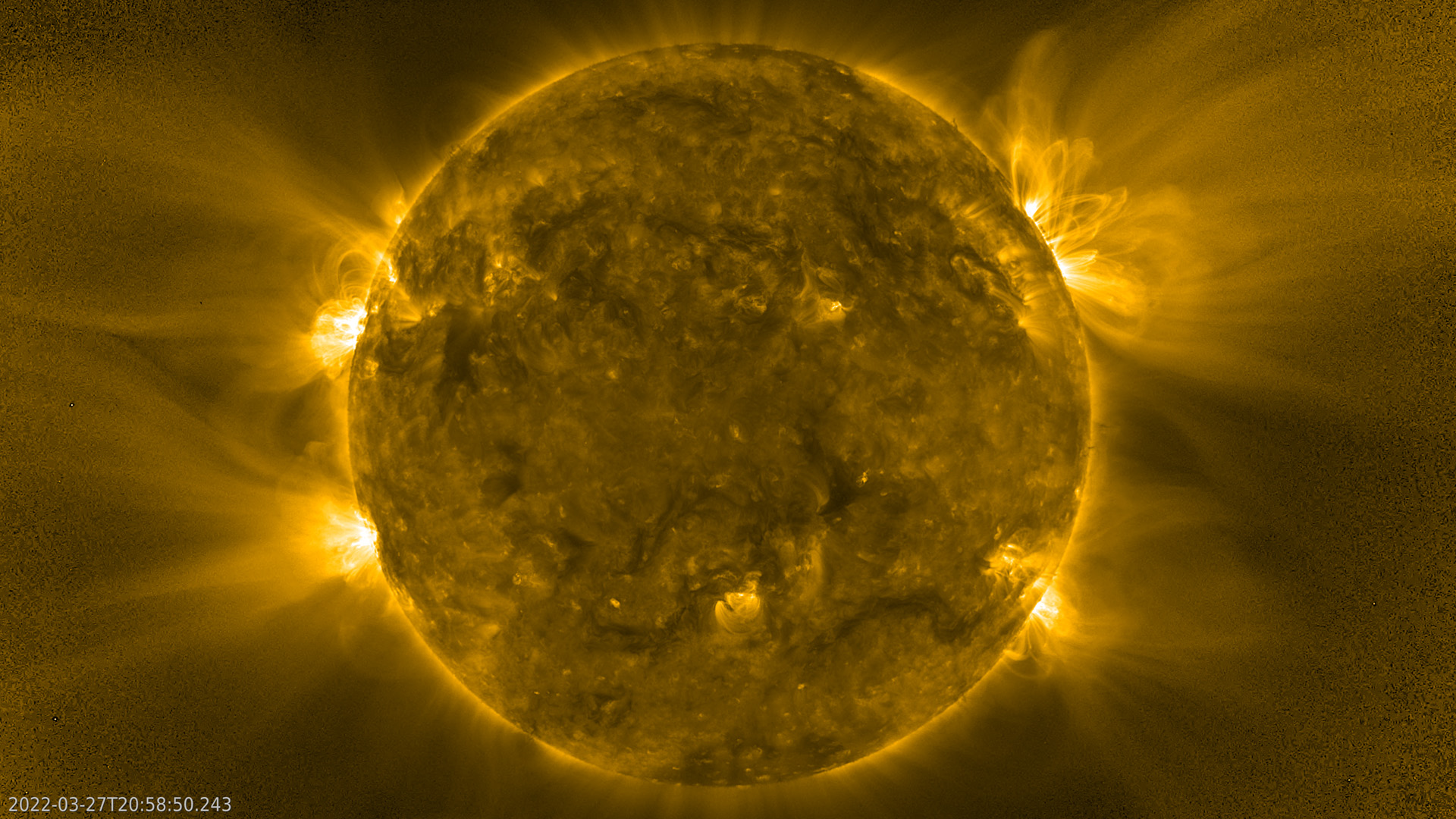

Since these stars are cooler than the sun, their habitable zones are much closer in than ours. That puts any planets there at risk of being hit with stellar eruptions or flares, which are common on red dwarfs. Such flares could release X-rays or ultraviolet radiation that could harm or inhibit the development of life, scientists say.

The new findings will be described in a paper to be published in an upcoming issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.