New Map of Distant Galaxies May Reveal Dark Energy History

Dark energy, the weird force blamed for propelling the universe to expand at an accelerated speed, probably turned on between 5 and 7 billion years ago, scientists think.

Now astronomers have mapped thousands of galaxies from this era, and have determined the most precise distances to them yet, in an effort to get to the bottom of the dark energy mystery.

Dark energy is thought to represent about 74 percent of the universe's total mass and energy, dwarfing ordinary matter. While its existence has never been directly confirmed, the strange force remains the leading explanation for why galaxies are speeding up as they spread farther and farther apart from each other.

"Ordinary matter is only a few percent of the universe," Ariel Sanchez, a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, said in a statement. "The largest component of the universe is dark energy — an irreducible energy associated with space itself that is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate."

But the expansion of the universe hasn't always been accelerating. Theorists think that before roughly 5 to 7 billion years ago, the expansion of the universe was slowing, due to the inward pull of gravity. Then, around that time, the expansion stopped slowing and started speeding up from the force of dark energy. [Images: The Big Bang & Early Universe]

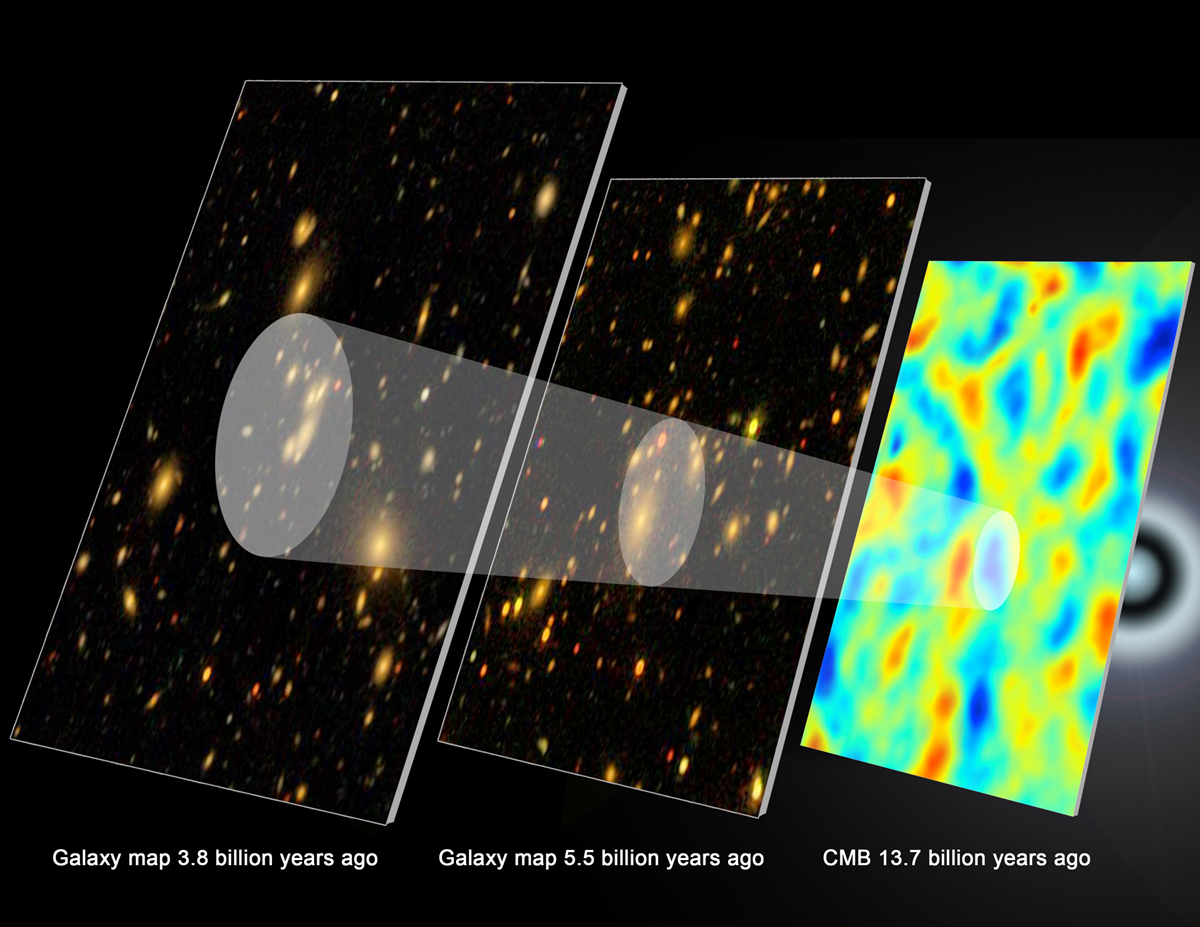

To study these changes in cosmic expansion, scientists must measure the distances between galaxies now, as well as during different epochs of the distant past. They can do this by looking at very distant galaxies whose light is only reaching us now after traveling billions of years, which can paint a picture of what the universe looked like billions of years ago.

Now, astronomers have created the most accurate map yet of galaxies in the distant universe, offering a window into the past and, possibly, into dark energy. The map comes from data collected by the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS), which is part of the third Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS-III).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The result is phenomenal," one of the leaders of the analysis team, Will Percival of the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. "We have only one-third of the data that BOSS will deliver, and that has already allowed us to measure how fast the universe was expanding six billion years ago — to an accuracy of two percent."

BOSS uses a custom designed instrument called a spectrograph on the SDSS 2.5-meter telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. The project aims to observe more than a million galaxies in six years.

The new findings come from observations BOSS made of 250,000 galaxies in its first year and a half of observations. As the project continues, astronomers expect even more revealing finds.

"For the past 13 years, we've had a simple model of how dark energy works," said David Schlegel of the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, BOSS' principal investigator. "But the truth is, we only have a little bit of data, and we're just beginning to explore the times when dark energy turned on. If there are surprises lurking out there, we expect to find them."

Researchers reported the first results from BOSS on March 30 at the National Astronomy Meeting in Manchester, England.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.