Sun's Sibling Stars Could Host Cousins of Earth Life

Some scientists are searching not just for any life out there in the universe, but for our distant relatives.

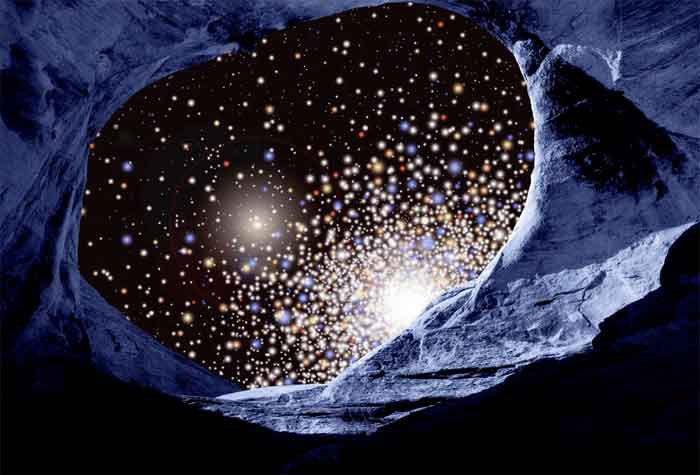

Earth may have seeded life on other planets if an asteroid smacking into Earth sprayed DNA into space, researchers suggest. Now a team of researchers is searching for siblings of the sun — stars born from the same parent star cluster — whose planets could have been impregnated with Earth life this way.

The sun's birth cluster

The sun is thought to have formed around 4.5 billion years ago within a cluster of thousands of baby stars. After around 1 billion years, this cluster broke up and the sibling stars went their separate ways. But before that point, researchers say, some of these stars may have shared life in the form of bacteria or DNA molecules.

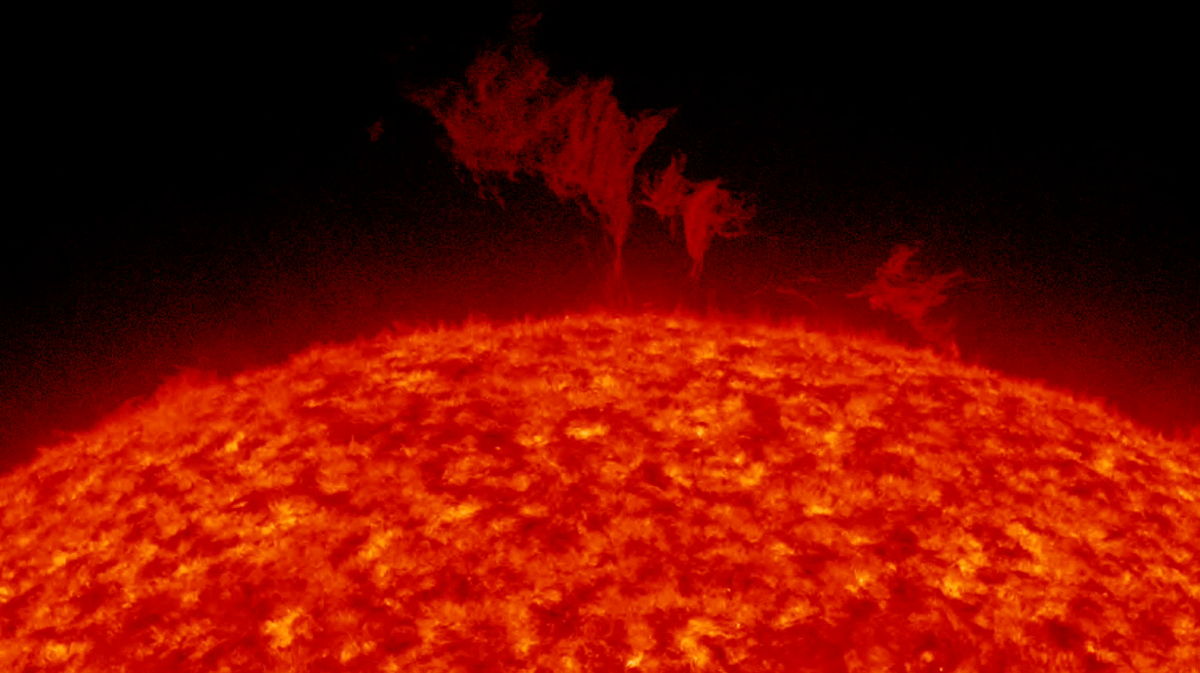

"The idea is if a planet has life, like Earth, and if you hit it with an asteroid, it will create debris, some of which will escape into space," said astronomer Mauri Valtonen of the University of Turku in Finland. "And if the debris is big enough, like 1 meter across, it can shield life inside from radiation, and that life can survive inside for millions of years until that debris lands somewhere. If it happens to land on a planet with suitable conditions, life can start there." [Gallery: The Smallest Alien Planets]

That means that somewhere out there in the galaxy might be your long-lost cousin.

If such a process ever happened, it was probably while the sun was still in its birth cluster, near enough to other stars that the chances were not negligible that debris bearing samples of Earth microorganisms might smash into another planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During the time of the birth cluster, objects in the solar system were under heavy bombardment by comets and asteroids, so researchers say material could have been fairly easily transferred between planets.

Research suggests it's equally possible that Earth itself was seeded with life in such a manner, though neither scenario is considered likely.

Searching for siblings

To pursue the idea, Valtonen is searching for these sibling stars of the sun.

In a recent study, he analyzed a catalog called HIPPARCOS that recorded the positions and motions of more than 100,000 stars. Picking out those stars with radial velocities known to be similar to the sun's, Valtonen and his colleagues identified two promising stars, called HIP 87382 and HIP 47399, that also had the same metal content and were at the same evolutionary stage as the sun. According to the researchers' analysis, there are a few percentage points of probability that these two were born in the same cluster as our sun. Both are about 100 light-years from Earth now.

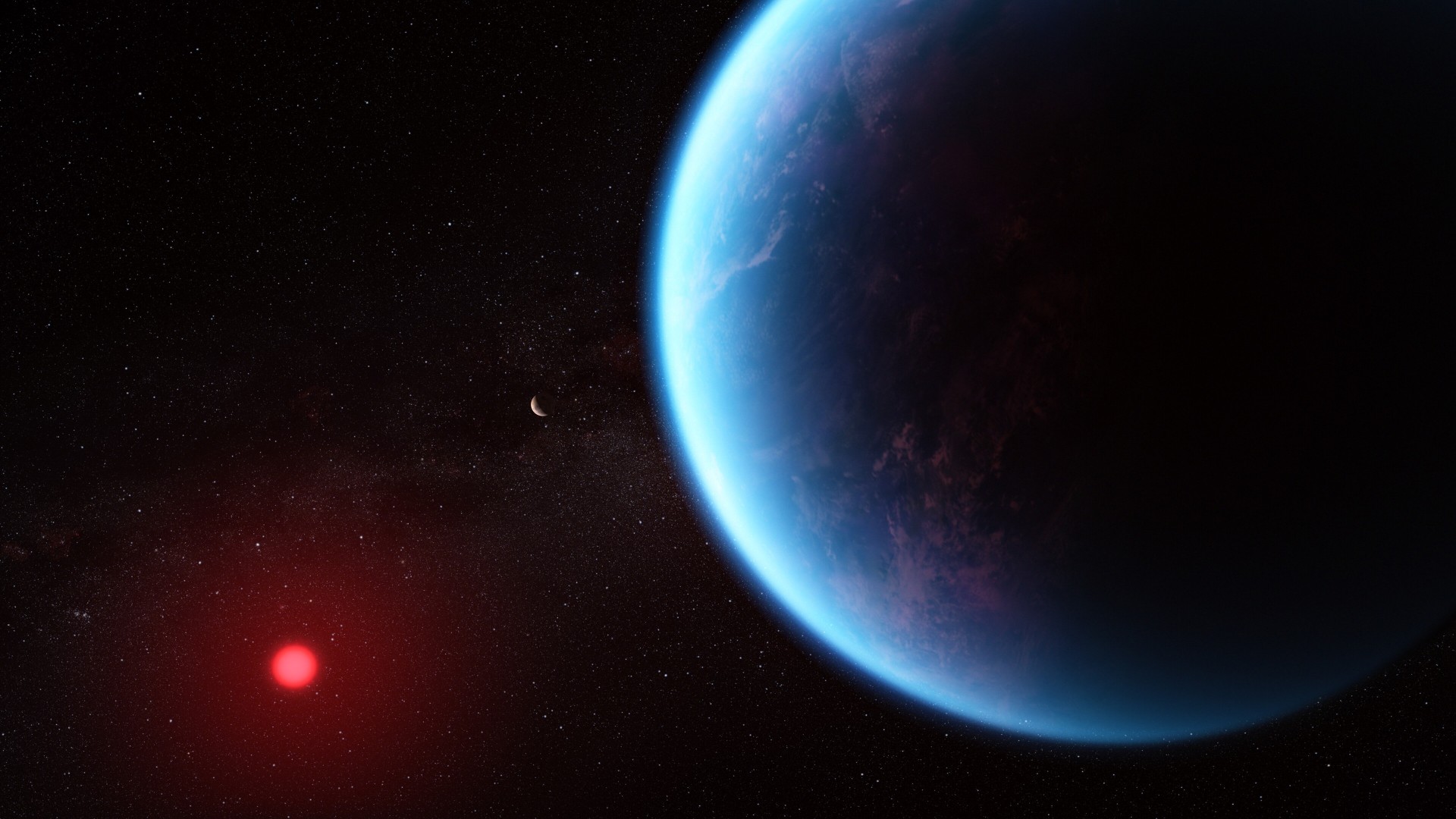

Valtonen said the next step would be to search for planets around these candidate stars.

"If we find an Earth-type planet, then it'd be a nice target for this new generation of detectors to point at the atmosphere of the planet," Valtonen told SPACE.com. "If there's a planet and it has signs of life, then we could say perhaps they are relatives in some sense."

Valtonen presented his findings earlier this year at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, in Austin, Texas.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.