How to See Saturn Reach Night Sky Milestone on April 15

When amateur astronomers reflect on the most memorable sights of their lifetimes, their first view of Saturn through a telescope usually ranks high. And this weekend offers a prime chance to see the ringed planet in the southern night sky.

I can still vividly remember my first reaction, even though it was nearly 55 years ago: "Wow—it really has rings!" Like everyone, I had seen many pictures of Saturn, but nothing prepared me for actually seeing a planet with rings with my own eyes. I've since shown Saturn to hundreds of people, and the most common reaction is total disbelief: "Is that a picture of Saturn you’ve got stuck inside your telescope?"

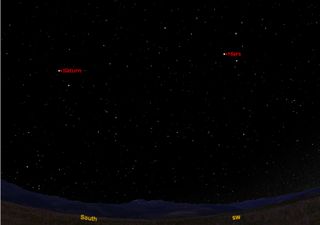

On April 15, Saturn reaches opposition — the point when it is directly opposite the sun in the sky. When it reaches opposition, Saturn will appear in the midnight sky to observers on Earth. The sky maps and illustration of Saturn accompanying this guide shows where to see the planet in the southern sky on April 15 and how it may appear seen through a good telescope.

The most important thing about this for skywatchers is that Saturn moves from being a "morning object" to being visible all night. For all of April, Saturn rises at sunset, and sets at sunrise.

Saturn's glorious rings

As gas giants go, Saturn is smaller and less active than Jupiter, but larger and more active than distant Uranus and Neptune. Like Jupiter, Saturn has alternating bands of lighter and darker hue, but mostly these are bland and featureless compared to the constant storms on Jupiter.

But Saturn's greatest glory is its rings.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

All the outer planets have rings, but with the exception of Saturn, they are only visible in long exposure photographs made from space. Saturn's rings are totally in your face, as bright as the planet itself. They are made up of many thousands of small pieces of rock and ice, with enough space in between for starlight to shine through. [Photos: Spectacular Views of Saturn's Rings]

From a distance they look substantial and solid, yet in reality they are gossamer thin: thousands of kilometers wide, yet only a few kilometers thick. Through a good telescope, the rings are seen to have a complex structure.

Three concentric rings may be visible through the telescope. The outer two are bright, cleanly separated by a dark gap named Cassini's Division after its discoverer, Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1625–1712); the innermost ring is ghostly faint, known as the crepe ring. On rare occasions, Saturn passes in front of a distant star, and that star continues to shine undiminished by its light's passage through the rings. It is from such occultations that we learned the particulate nature of Saturn's rings.

Saturn, the cosmic egg

In binoculars, it’s clear that Saturn is egg-shaped rather than circular, but the true nature of its rings isn’t apparent until seen in a telescope with at least 25 power magnification. To see that the rings are multiple requires at least 150 power, good optics, and steady seeing.

Like Jupiter, Saturn is accompanied by a retinue of more than 60 moons. In Jupiter's case, four of these moons are large and bright while the rest are small and faint. Saturn's moons are graduated evenly in size. How many of Saturn's moons you may see is directly related to the size of your telescope and the acuteness of your vision.

Here’s a list of the brightest moons and their brightness on April 15, the night of Saturn's opposition:

- Titan: 8.4

- Rhea: 9.7

- Tethys: 10.2

- Dione: 10.4

- Iapetus: 11.1

- Enceladus: 11.7

Astronomers use an upside down magnitude scale: the larger the number, the fainter the object. At magnitude 8.4, Titan is easily visible in binoculars. One of the two largest moons in the solar sytem, it is the only moon with a substantial atmosphere, mostly methane gas. It was visited by the Huygens lander on Jan. 14, 2005. [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

Rhea, Tethys, and Dione are the next brightest moons, visible in a 90mm telescope. Enceladus orbits very close to the rings, and is usually overwhelmed by their brightness and difficult to spot. These five moons all orbit in the same plane as the rings, so describe symmetrical ovals around Saturn.

Iapetus is the odd-ball among Saturn’s moons. It orbits in a different plane that the rings and other moons, and travels quire far from the planet. Because its path takes it through debris fields, its leading side has become coated with dark material, so that it is much fainter on one side of Saturn than it is on the other.

All the major moons in the solar system, including our own moon, are tidally locked to their primaries: they always keep the same face turned inwards towards their planet. Seen from the surface of Saturn, Iapetus would appear to be half black and half white.

With so many moons visible in a telescope, how do you tell which is which? The easiest way is to run a planetarium program on your computer: it will plot accurately the positions of all of Saturn’s moons as they circle the planet, neatly labeled for you.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.