Asteroid Impacts Could Help out Underground Life

An incoming asteroid is trouble whether you're a dinosaur or a Bruce Willis fan. But microbes living deep underground may actually welcome the news, according to a recent study of an ancient impact in the United States' Chesapeake Bay. A biological census of the subsurface life forms suggests that impacts create new niches for these deep dwellers to spread into.

In the last couple of decades, biologists have come to realize that the biosphere doesn't stop at the surface. A large fraction of the Earth's biomass is lurking down below. Several drilling projects have brought up evidence of hearty little microbes thriving in deep rock sediments. Some eat organic scraps that seep down from our world, while others derive energy through chemical reactions with iron and sulfur.

Although it's hardly paradise, this netherworld has one thing going for it: it's fairly peaceful. There's no night or day, no winter or summer. No global warming or ice ages to worry about. Only the occasional earthquake or asteroid impact is really going to shake things up.

We typically think that crust-shattering asteroids or comets have only detrimental effects on life, but the opposite may be true for subterranean microbes. An impact will sterilize some of the rock with heat, but it will also make other areas more habitable. [5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids]

"Impacts can fracture the rocks in the deep surface, which will allow fluids and nutrients to flow in," said Charles Cockell from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

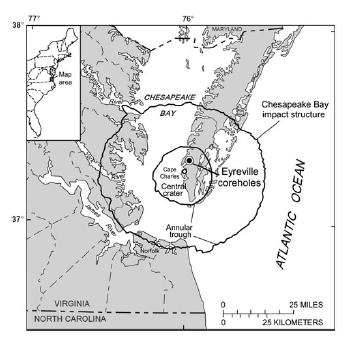

Cockell and his colleagues decided to look at the subsurface life beneath one of the largest impact craters on Earth, the 53-mile-wide (85 kilometer) crater in the Chesapeake Bay along the U.S. East Coast. Their results, reported in a recent paper in the journal Astrobiology, suggest that the underground biosphere is still adapting to the 35-million-year-old impact. But it does appear that some microbes took advantage of the cataclysm to settle down deeper in the underworld.

Big dig

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Chesapeake Bay impact crater is the largest in the United States, but geologists discovered it only in 1983. It was created 35 million years ago when a comet or asteroid about 0.6 miles (1 km) struck the shallow coastal waters there.

"It carved out a deep hole, but material on the perimeter immediately slumped in," Cockell said. Models suggest that around 30 minutes later, the hole filled in when tsunami waves swept over the impact site and deposited a thick layer of fresh sediments.

The energy from the impact heated the rock at the base of the crater to more than 660 degrees Fahrenheit (350 degrees Celsius). This would have killed all the life hiding in the shallow subsurface. But as the rock cooled, life would have come to reclaim this disaster area.

"How long it would take them to move in depends on the porosity of the rock," Cockell said.

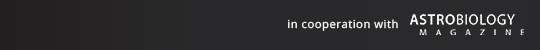

To study the aftermath, a project headed by the International Continental Drilling Program and the United States Geological Survey drilled down into the impact crater in 2005 and 2006 to recover core samples down to a depth of 1.1 miles (1.76 km; Aaron Gronstal, one of the participants, wrote a personal account of the dig).

The geological examination of the drill cores showed that the first 0.28 miles (0.45 km) below the surface is sediment from more recent times. Between 0.28 and 0.6 miles (0.45 and 1 km), one finds "post impact" material that was swept back into the crater by the tsunami waves. The rock beneath about 0.6 miles was directly shocked and heated by the impact.

Cell counting

During the drilling process, biologists extracted samples from the rock in order to take a census of life in the impact crater. A total of 88 samples were collected from a wide range of depths.

Each sample was dissolved in solution and put in cold storage. At a later date, the researchers added a DNA-binding dye to each sample and placed them under a microscope. Individual microbes were counted by eye. [Extremophiles: World's Weirdest Life]

"It's long and tedious," Cockell said. "But this is fairly standard way to do it."

The team took special precautions to avoid contamination from "non-native" life forms. Different markers were added to the drilling mud during the drilling process. If any of these markers showed up in a biological sample, then the team would know that stuff had gotten in from outside.

Restricting themselves to only the uncontaminated samples, the biologists found that the number of microbes per gram of rock decreased with depth, as is commonly observed at other drill sites. But in the impact-affected regions, there was a higher than usual amount of variation, as if the biosphere hadn't yet come back to equilibrium.

The researchers showed that this variation, or patchiness in the microbial distribution, was not because of some lack of nutrients. In fact, they found an abundance of sulfate and organic carbon throughout the drill core. The implication seems to be that 35 million years hasn't been enough time for the microbes to fill in the churned up rock from the impact.

"It's not a big surprise that it takes them millions of years to do it," Cockell said. "They have to get through impermeable sediments."

Breaking ground for new settlements

Deeper down, below about 0.6 miles, the researchers found an unusually high number of microbes, about a million cells per gram.

"No one has observed that many organisms at this depth," Cockell said.

The conclusion seems to be that the impact actually benefitted the microbes by enlarging the area where they could roam. The resulting fissures and cracks let in water and other nutrients into this deep rock, which made these areas more hospitable for deep-Earth dwellers.

"We should change the view of impacts, said Stephen Mojzsis of the University of Colorado, Boulder, who was not involved in the project. "We shouldn't see them as only destructive. They are a natural mechanism for opening up niches for the microbial community."

Mojzsis has argued that life may have prospered underground during the Late Heavy Bombardment when the Earth was pummeled with large impactors around 4 billion years ago. Although he believes microbes will re-colonize an impact crater faster than the authors claim to observe here, he does commend this "very thorough" study for quantitatively assessing the habitability of impact craters.

Mojzsis also agrees with the authors that craters may be a good place to look for signs of life on other worlds. Just as on Earth, impacts could have opened up new habitats for organisms that may have once lived on Mars.

"This may guide our hand in choosing a drill site for a future Mars mission," Mojzsis said.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.