Sand Dunes on Mars Are Surprisingly Speedy

This story was updated on May 10 at 11 a.m. ET.

Towering sand dunes on Mars, once thought to be ancient and unchanging, are actually dynamic and active today, new satellite observations show.

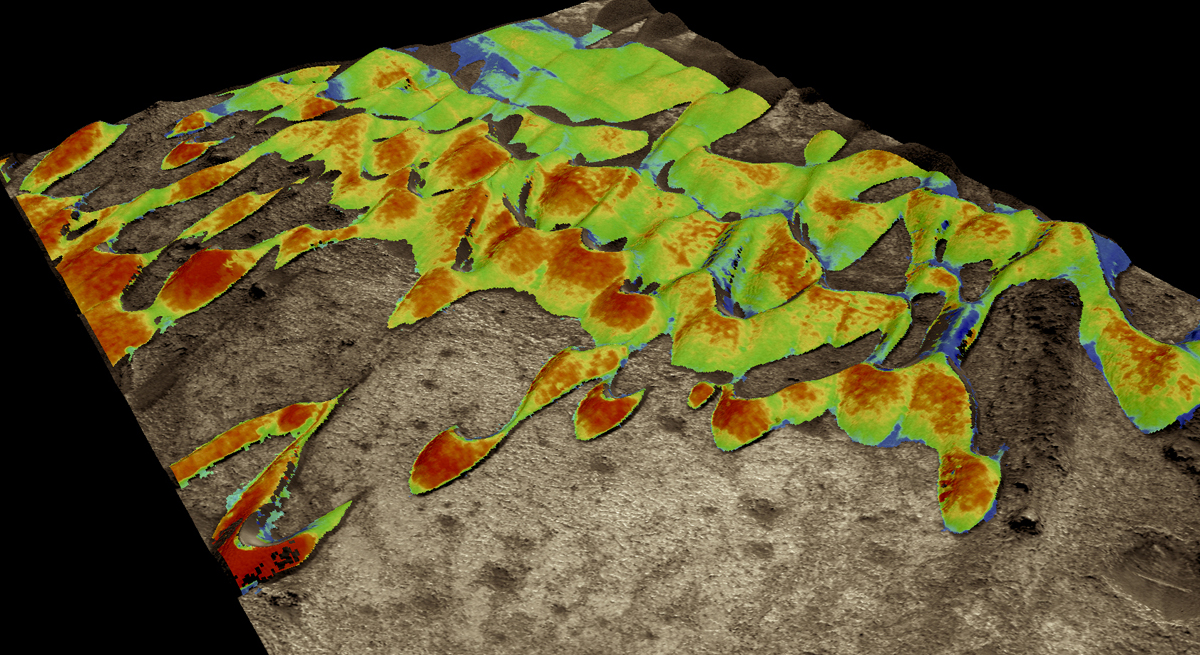

Using advanced optical images taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, scientists tracked the horizontal and vertical motion of sand over time with unprecedented detail.

"We can actually see movement, potentially, of just a few centimeters," planetary geologist Nathan Bridges of Johns Hopkins University told SPACE.com.

Sand in motion

Bridges and his team studied the Nili Patera dune field just north of the Martian equator, taking detailed images over 105 days. If the same resolution were used on Earth, the results would be classified.

The team used a computer program developed at the California Institute of Technology previously used to examine earthquakes and landslides on Earth to measure the motion of the sand ripples on top of the dunes very precisely. [Video: Sand Dunes Crawl Across Mars Surface]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our new data shows wind activity is indeed a major agent of evolution of the landscape on Mars," said Jean-Philippe Avouac, the Caltech team leader, in a statement. "This is important because it tells us something about the current state of Mars and how the planet is working today, geologically."

The researchers found that some of the surface ripples traveled as much as 15 feet (4.5 meters) over the course of the study. Fast dunes may travel a distance equal to their length over 170 years, while slower dunes take a few thousand years to move. Interestingly, the dunes in the Nili Patera move similarly to those in Victoria Valley, Antarctica, on Earth.

Bridges previously worked on a 2010 study that first identified Martian dune motion in the Nili Patera region. So when he wanted a more detailed look at sand dunes, the region seemed like a good place to start.

"We thought, let's test this technology on an area where we know the motion is occurring," Bridges said.

Located on a volcanic feature inside the Syrtis Major region, Nili Patera is a crater with an opening at one end that allows dunes to blow inside of it. However, this area of Mars isn't likely to be unique.

"There's no reason to think that we would not see this in some other areas of Mars, as well," Bridges said.

The researchers intend to examine the dune and ripple motion on other areas of Mars, including regions where the motion may not be obvious without their technique.

A sand-scoured landscape

For a long time, the thin atmosphere on Mars was thought to hinder significant motion of sand across its surface. In order to lift sand from the ground, winds must be about ten times faster than required on Earth.

"These winds do occur on Mars, but they occur very rarely, much more rarely than they do on Earth," Bridges said.

But independent research has shown that the thin atmosphere and the lower gravity may help sustain the motion of the sand by allowing the sand to travel farther and faster without impediment. After the sand has been lifted, the winds needed to keep it moving are only a tenth of the strength of the originating winds.

When grains of sand touch down on the surface, the new grains they kick up travel short distances to create ripples across the dunes. Again, the wind needed to keep them in motion is significantly less than the wind needed to start the process.

This method of travel, suggested independently for the motion of sand on Earth, would explain how Martian dunes are moving despite the fact that the high winds needed to jumpstart the grains are few and far between.

"You need very rare winds to start the sand moving, but once it starts moving, you can keep it going with winds that are more common," Bridges explained.

The research, which will appear in an upcoming edition of the journal Nature, also looks at how much rock can be eroded by wind-blown sand. The team found that as much as 50 microns (millionths of a meter) of rock per year could be scoured away.

"A lot of sand can be moved in the current atmosphere," Bridges said. "By implication, that landscape modification through abrasion by the sand can be significant in the current atmosphere, even though the atmosphere is very thin."

Features on Mars can still suffer erosion by sand, so they may continue to change over time.

"Past climates and such are not necessary to explain the features that we see," he said.

This story was updated to include more details on the Caltech software tool used in the study.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd