How Was Mars Made? | Formation of Mars

The planet Mars was formed, along with the rest of the solar system, about 4.6 billion years ago. But exactly how the planets formed remains a subject of debate. Currently, two theories are duking it out for the role of champion.

The first and most widely accepted theory, core accretion, works well with the formation of the terrestrial planets like Mars but has problems with giant planets. The second, the disk instability method, may account for the creation of these giant planets.

Scientists are continuing to study planets in and out of the solar system in an effort to better understand which of these methods is most accurate.

The core accretion model

The leading theory, known as core accretion, is that the solar system began as a large, lumpy cloud of cold gas and dust, called the solar nebula. The nebula collapsed because of its own gravity and flattened into a spinning disk. Matter was drawn to the center of the disk, forming the sun.

Other particles of matter stuck together to form clumps called planetesimals. Some of these combined to form asteroids, comets, moons and planets. The solar wind — charged particles streaming out from the sun — swept away the lighter elements, such as hydrogen and helium, leaving behind mostly small, rocky worlds. In the outer regions, however, gas giants made up of mostly hydrogen and helium formed because the solar wind was weaker.

Exoplanet observations seem to confirm core accretion as the dominant formation process. Stars with more "metals" — a term astronomers use for elements other than hydrogen and helium — in their cores have more giant planets than their metal-poor cousins. According to NASA, core accretion suggests that small, rocky worlds should be more common than the more massive gas giants.

The 2005 discovery of a giant planet with a massive core orbiting the sun-like star HD 149026 is an example of an exoplanet that helped strengthen the case for core accretion.

"This is a confirmation of the core accretion theory for planet formation and evidence that planets of this kind should exist in abundance," said Greg Henry in a press release. Henry, an astronomer at Tennessee State University, Nashville, detected the dimming of the star.

In 2018, the European Space Agency plans to launch the CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), which will study exoplanets ranging in sizes from super-Earths to Neptune. Studying these distant worlds may help determine how planets in the solar system formed.

"In the core accretion scenario, the core of a planet must reach a critical mass before it is able to accrete gas in a runaway fashion," said the CHEOPS team.

"This critical mass depends upon many physical variables, among the most important of which is the rate of planetesimals accretion."

By studying how growing planets accrete material, CHEOPS will provide insight into how worlds grow.

Core accretion was first postulated in the late 18th century by Immanuel Kant and Pierre Laplace. Nebula theory helps explain how the planets in our solar system were formed. But with the discovery of "Super-Earth" planets orbiting other stars, a new theory, known as disk instability was proposed.

The disk instability model

Although the core accretion model works fine for terrestrial planets, gas giants would have needed to evolve rapidly to grab hold of the significant mass of lighter gases they contain. But simulations have not been able to account for this rapid formation. According to models, the process takes several million years, longer than the light gases were available in the early solar system. At the same time, the core accretion model faces a migration issue, as the baby planets are likely to spiral into the sun in a short amount of time.

According to a relatively new theory, disk instability, clumps of dust and gas are bound together early in the life of the solar system. Over time, these clumps slowly compact into a giant planet. These planets can form faster than their core accretion rivals, sometimes in as little as a thousand years, allowing them to trap the rapidly-vanishing lighter gases. They also quickly reach an orbit-stabilizing mass that keeps them from death-marching into the sun.

According to exoplanetary astronomer Paul Wilson, if disk instability dominates the formation of planets, it should produce a wide number of worlds at large orders. The four giant planets orbiting at significant distances around the star HD 9799 provides observational evidence for disk instability. Fomalhaut b, an exoplanet with a 2,000-year orbit around its star, could also be an example of a world formed through disk instability, though the planet could also have been ejected due to interactions with its neighbors.

Pebble accretion

The biggest challenge to core accretion is time — building massive gas giants fast enough to grab the lighter components of their atmosphere. Recent research on how smaller, pebble-sized objects fused together to build giant planets up to 1000 times faster than earlier studies.

"This is the first model that we know about that you start out with a pretty simple structure for the solar nebula from which planets form, and end up with the giant-planet system that we see," study lead author Harold Levison, an astronomer at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Colorado, told Space.com in 2015.

In 2012, researchers Michiel Lambrechts and Anders Johansen from Lund University in Sweden proposed that tiny pebbles, once written off, held the key to rapidly building giant planets.

"They showed that the leftover pebbles from this formation process, which previously were thought to be unimportant, could actually be a huge solution to the planet-forming problem," Levison said.

Levison and his team built on that research to model more precisely how the tiny pebbles could form planets seen in the galaxy today. While previous simulations, both large and medium-sized objects consumed their pebble-sized cousins at a relatively constant rate, Levison's simulations suggest that the larger objects acted more like bullies, snatching away pebbles from the mid-sized masses to grow at a far faster rate.

"The larger objects now tend to scatter the smaller ones more than the smaller ones scatter them back, so the smaller ones end up getting scattered out of the pebble disk," study co-author Katherine Kretke, also from SwRI, told Space.com. "The bigger guy basically bullies the smaller one so they can eat all the pebbles themselves, and they can continue to grow up to form the cores of the giant planets."

In 2018, NASA will launch the InSight mission to Mars that will study the planet's interior.

"But InSight is more than a Mars mission — it is a terrestrial planet explorer that will address one of the most fundamental issues of planetary and solar system science — understanding the processes that shaped the rocky planets of the inner solar system (including Earth) more than four billion years ago," according to NASA.

"InSight seeks to answer one of science's most fundamental questions: How did the terrestrial planets form?"

Shrinking down

Whether Mars got its start through disk instability or core or pebble accretion, it continued to pack on the weight as it grew. Models suggest that the Red Planet should be about as large as Venus and Earth if gas and dust were smoothly spread through the solar system. Instead, Mars is only 10 percent as massive, suggesting that it formed in a region low on planetary building blocks.

Enter the Grand Tack model, the leading theory to explain the so-called "small Mars problem." According to the model, Jupiter and Saturn migrated toward the sun shortly after their birth before tacking like a sailboat and returning to the outer solar system. Along the way, they would have swept up much of the debris that should have fed Mars' formation.

"Provided that Jupiter changed direction close to 1.5 AU, the growth of Mars would be successfully stunted while leaving enough material closer to the sun to form Earth and Venus," John Chambers of the Carnegie Institution for Science wrote in a 2014 "Perspectives" piece published in the journal Nature.

Another possibility is that regions of low density formed naturally in the protoplanetary disk.

"If this partial gap survived long enough, it could have been preserved in the distribution of planetesimals and planetary embryos that formed subsequently," Chambers writes. "The simulations performed by Izidoro show that reducing the number of planetary building blocks near Mars' current orbit by 50 to 75 percent favors the formation of a puny Red Planet."

Another option is that Mars actually got its start in the asteroid belt, then migrated toward the sun because of its interaction with planetesimals.

"Since Mars is more massive than the planetesimals, it tends to lose energy when it scatters these planetesimals because it passes them to Jupiter, which then ejects them from the solar system," Ramon Brasser, lead author and associate professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology's Earth-Life Science Institute, told Space.com.

Heating and cooling

Like all planets, Mars became hot as it formed because of the energy from these collisions. The planet's interior melted and denser elements such as iron sank to the center, forming the core. Lighter silicates formed the mantle, and the least-dense silicates formed the crust. Mars probably had a magnetic field for a few hundred million years, but as the planet cooled, the field died.

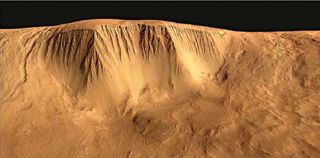

The young Mars had active volcanoes, which spewed lava across its surface, and water and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. But there is no tectonic activity on Mars, so the volcanoes remained stationary and grew with each new eruption.

The volcanic activity also probably gave Mars a thicker atmosphere. Mars' magnetic field protected the planet from radiation and solar wind. With a higher atmospheric pressure, water probably flowed on Mars' surface, studies indicate. But about 3.5 billion years ago, Mars began to cool. Volcanoes erupted less and less and the magnetic field disappeared. The unprotected atmosphere was blown away by solar wind and the surface was bombarded by radiation.

Under these conditions, liquid water cannot exist on the surface. Studies suggest water is be trapped underground in both liquid and frozen forms and in the ice sheets of the polar ice caps.

All life as we know it requires liquid water, so there is much interest in finding evidence of it on Mars.

— Additional reporting by Nola Taylor Redd, Space.com Contributor

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!