How a Mars Sample Return Mission Can Go Electric

Solving the mystery of life on Mars requires robots to collect Martian samples for a return to Earth — a mission that may come with the astronomical price tag of $5 billion to $10 billion. That round trip to the Red Planet could become cheaper by using electric propulsion.

The Mars sample return (MSR) mission would require powerful electric thrusters and efficient solar panels which are presently under development worldwide or even already existing. Such technology would allow the Mars mission to lighten the load of chemical propellant carried by traditional rockets and spacecraft — and it's within reach for a mission to try recovering Martian rocks and soil in the next decade or two.

"The chances of having a reliable technology available for MSR in the timeframe beyond 2020 appear good," said Wolfgang Seboldt, a physicist at the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

Having electric propulsion could also speed up the round trip to Mars. The total mission time could prove especially helpful for any eventual human missions to Mars because of the risk that, for example, high-energy cosmic rays pose to astronauts during the journey. [Boldest Mars Missions Ever]

Harnessing the power of sunlight

Most space missions burn chemical propellants to get a big boost up front that lasts as long as the propellant supply. Such chemical propulsion has allowed the huge Apollo rockets and the retired space shuttle fleet to escape Earth's gravity and get into orbit, and would serve a similar purpose for launching any mission to Mars.

The Mars mission could switch over to using electric propulsion once it reaches Earth orbit and begins the journey to Mars, Seboldt said. That would start off slowly by converting xenon gas propellant into a stream of electrically-charged ion particles, but build up to high speed over time with a practically unlimited supply of electricity from solar panels.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Mars orbiter spacecraft could end up flying the Mars round trip cheaper and at least as fast as traditional chemical propulsion missions (if not faster), even if it has to carry the added mass of large solar panels. The "propellant mass saving over-compensates the mass increase from the large solar arrays," Seboldt explained. [Mars Landings: How Much Better Are We? (Video)]

Planning the Mars trip

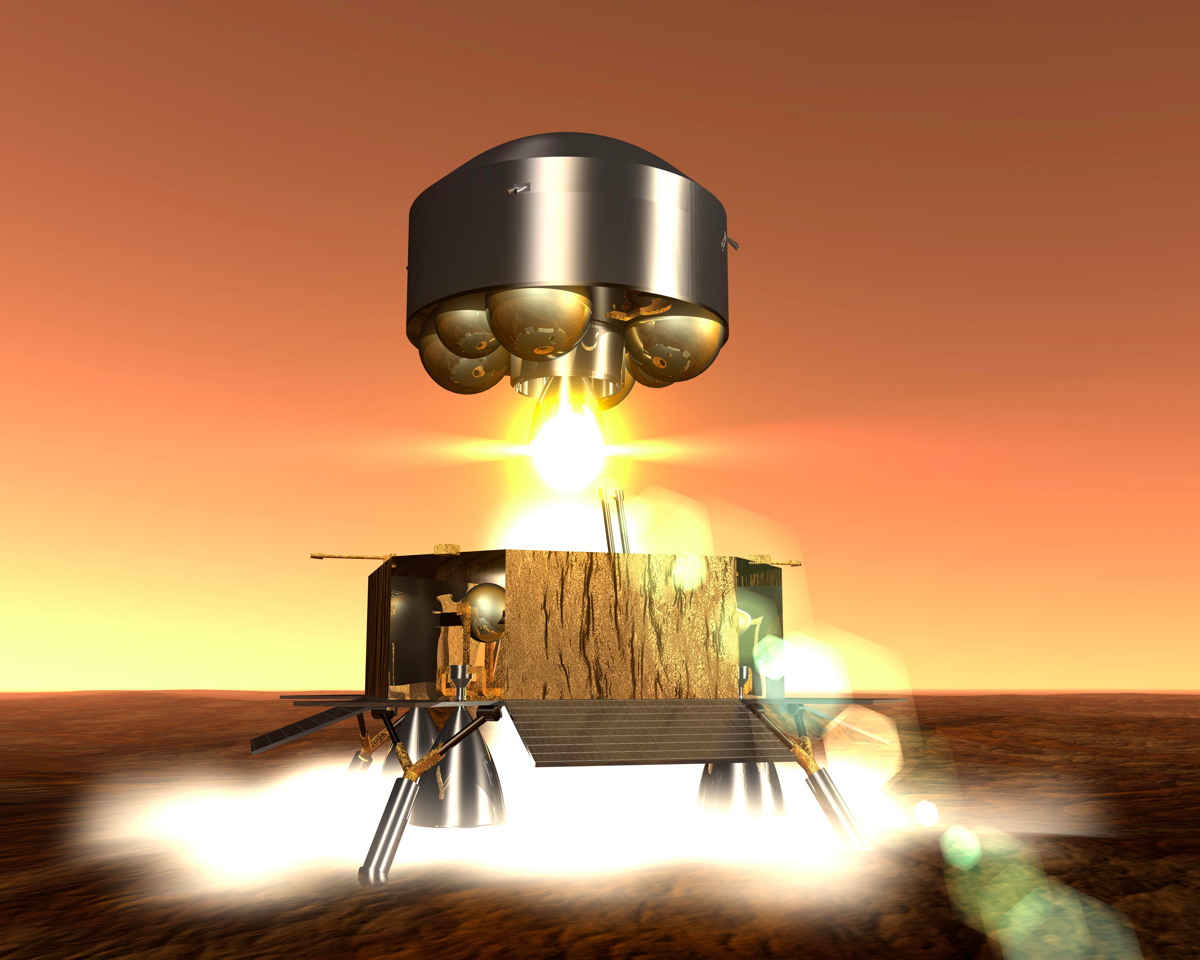

The conventional mission scenario includes two spacecraft launched separately from Earth — an orbiter and a lander. The lander sets down on the Red Planet to collect samples. An ascent vehicle carrying the samples would then take off from the Martian surface using traditional chemical propellants, so that it can rejoin the orbiter for the return trip to Earth.

A hybrid version of the conventional mission scenario would involve the orbiter using electric propulsion. In an advanced scenario, the lander could even ride the electric orbiter, piggy-back style, to reach the red planet.

The lighter load of propellant would mean the electric Mars orbiter in the conventional scenario could launch from Earth aboard a medium rocket such as the Soyuz-Fregat, rather than the heavy rocket Ariane 5 ECA. The most barebones mission scenario could also use a 20-kilowatt solar array with power requirements similar to those of communication satellites in geostationary orbit above the Earth.

The risks of solar electric

But Seboldt and his colleague, Uwe Derz, also pointed to some risks and unknowns in their proposal detailed in the August-September issue of the journal Acta Astronautica. For instance, their paper only looked at a limited number of launch windows around the 2020 timeframe.

The cost of the electric Mars mission depends on the propulsion system's cost and whether or not it's more expensive than the possible saving of launch costs. That depends in large part upon whether parts from other spacecraft can be reused — such as Europe's similar BepiColombo mission to Mercury planned for 2015.

Some mission planners at space agencies also have concerns regarding the reliability and lifetime of electric propulsion technology, according to Seboldt. In addition, solar arrays face possible damage from solar cosmic rays that also threaten orbiting satellites and the International Space Station.

Powering ahead

Still, solar electric propulsion technology has gotten a boost in recent years. U.S. aerospace giant Boeing plans to use such propulsion in more of its geostationary satellites — both for moving into geostationary orbit and maintaining orbit — opening up the market and pushing technological development for all spacecraft and satellites.

The European Space Agency plans to have solar arrays providing up to 30 kilowatts of power and thruster systems operating in the 20 kilowatt range beyond the 2020 timeframe. Meanwhile, tests on satellites and aboard the space station could boost confidence in the technology.

"Possibly the International Space Station may be a good place for testing newly developed thrusters under extreme space conditions," Seboldt said. "Also, the power supply with large deployable, lightweight and efficient solar arrays must be studied."

A recent Moscow conference called the "4th Russian-German Conference on Electric Propulsions and Their Application 2012: Electric Propulsions. New Challenges" highlighted a Mars sample return mission using solar electric propulsion as being very promising.

If the optimism proves true, solar electric propulsion could do more than help shed light on life on Mars — it could also propel human missions to the Red Planet or beyond.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.