Taking a 1-ton Mars rover out for a Red Planet spin may be an otherworldly adventure, but it isn't full of heart-pumping action like a video game.

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity is set to make its first test drive Wednesday (Aug. 22), then head out toward a spot called Glenelg in the coming days. Curiosity's drivers will guide the six-wheeled robot on the 1,300-foot (400-meter) trek to Glenelg — not with a joystick, but via commands uploaded on a daily basis.

"The rover may be powered off while we're actually doing our planning, and so we'll have eight or more hours to do our sequencing," said Jeff Biesiadecki of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Then we'll send up a command load to the rover and tell it step-by-step what it needs to do."

Team of drivers

Biesiadecki is one of 16 drivers for Curiosity, which touched down inside Mars' huge Gale Crater on the night of Aug. 5. The rover is the heart of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory mission (MSL), which aims to determine if the Red Planet could ever have supported microbial life.

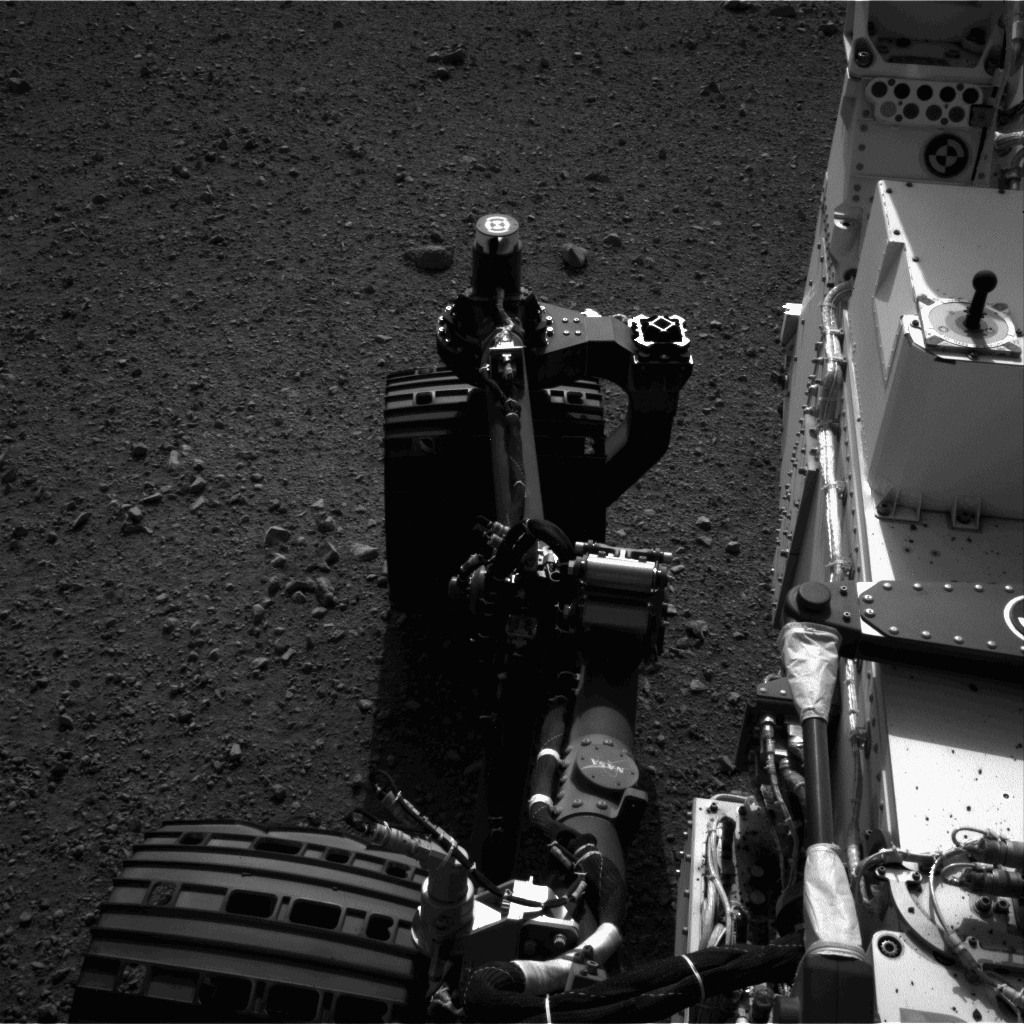

The rover drivers don't just focus on moving Curiosity's wheels, Biesiadecki said. They also operate its 7-foot (2.1-m) robotic arm, which is equipped with a percussive drill and soil-scooping gear, among other tools. And the drivers work to make sure samples snagged by the arm get deposited into the analysis instruments on Curiosity's body. [Latest Mars Photos by Curiosity Rover]

Such activities are generally mapped out a day ahead of time by the rover science team, then written up as code by the drivers.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So Curiosity has its orders when it rises to greet each Martian day, or "sol." The rover team doesn't want to plan things out too far in advance, scientists have said, because priorities can change from sol to sol depending on what Curiosity finds.

Curiosity carries 17 different cameras to help it study and negotiate the Gale Crater terrain. The drivers are particularly interested in photos snapped by Curiosity's four navigation cameras, which sit on its head-like mast.

"We get a stereo view of Mars from those cameras," Biesiadecki told SPACE.com "Those [images] are a key element of helping us decide where we're going to go the next day, and what routes are safe. So basically, after the rover downlinks its imagery, then all our planning takes place."

Some autonomy

While Curiosity is ultimately dependent on its Earth-bound handlers, it does have an autonomous navigation mode that allows it a bit of freedom on the Martian surface.

"The rover is going to be able to choose its own path," Biesiadecki said of this mode. "It will take images as needed to look for obstacles along the way, and drive around them. The disadvantage is that it's much slower for it to do that."

Curiosity's autonomous mode will come in handy when the MSL team wants to send the rover somewhere not covered by the previous day's set of images, Biesiadecki said. But the drivers won't test out this capability right off the bat.

"Our initial drives are going to be in the much more 'do exactly what we tell you to do' mode," Biesiadecki said. "So that will be, 'Drive this many meters; stop, turn this much; take an image; drive this many more meters.'"

NASA officials have called Curiosity the most complex and capable robotic explorer ever sent to another planet. But driving it is similar to operating the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, which landed on the Red Planet in January 2004, Biesiadecki said. Opportunity is still roving across the Martian landscape today, more than eight years later.

"We really tried to build on the experience that we had from MER," Biesiadecki said. "We've got the same drive pattern. We have the same engineering cameras onboard, for instance, and so that dictates a lot of how we do our work." [Latest Mars Photos from Spirit and Opportunity]

Taking it slow

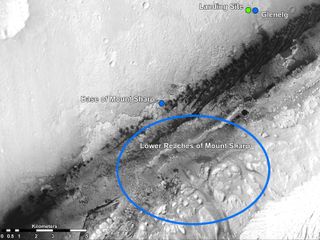

Curiosity's first substantial drives will send it toward Glenelg, where three different types of geological terrain come together in one place.

Though Glenelg is just four football fields away, it'll probably take Curiosity a month or more to get there, mission managers have said. That's because Curiosity will take things slow initially, and scientists may want to stop along the way to do some science work.

Curiosity's ultimate destination, however, is the base of Mount Sharp, the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) mountain rising from Gale Crater's center. Mars-orbiting spacecraft have spotted evidence of clays and sulfates in Mount Sharp's foothills, suggesting the area was exposed to liquid water long ago.

The interesting Mount Sharp deposits are about 5 miles (8 km) away from Curiosity's landing site as the crow flies, so getting to them will be quite a trek, especially since the rover is not exactly a speed demon. The MSL team hopes Curiosity can eventually cover 330 feet (100 m) or more of Martian ground in a big day of driving.

Biesiadecki and his fellow drivers are eager to get Curiosity headed toward Glenelg, and then on to Mount Sharp.

"For all rover planners, I think I can safely say we're itching to go, and Curiosity's ready to roll," Biesiadecki said.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.