NASA Cooks Up Icy Organics to Mimic Life's Origins

Complex molecules can begin the transformation into life's building blocks in the frigid depths of deep space, a new study suggests.

Researchers brewed up concoctions of organics — carbon-containing compounds — in icy conditions in the lab, then blasted them with radiation akin to that streaming from stars. They found that the organics morphed into the types of molecules that could have jump-started life on Earth.

"The very basic steps needed for the evolution of life may have started in the coldest regions of our universe," lead author Murthy Gudipati, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "We were surprised to see organic chemistry brewing up on ice, at these very cold temperatures in our lab."

The origin of life's building blocks

Many scientists think that the basic ingredients of life on Earth, including water and organic compounds, ultimately got their start on particles in the freezing outer reaches of the solar system. These particles glommed onto comets and asteroids, then found their way to our planet via long-ago impacts. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

The exact steps needed to go from icy organics to life's building blocks remain unclear, but the new study may shed some light on the basic processes, researchers said. And it shows that the first steps can take place while the organics are still frozen in deep space.

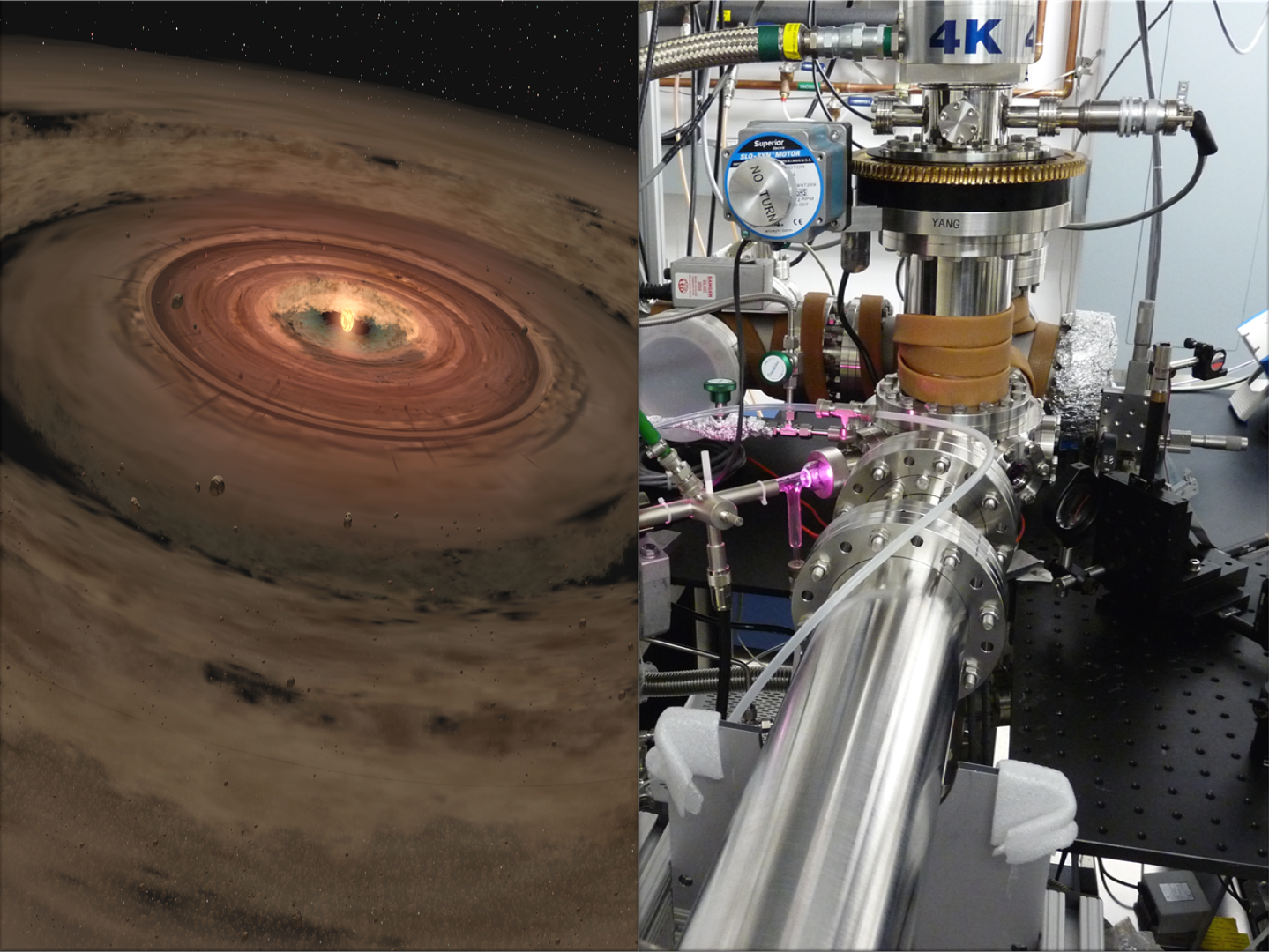

Gudipati and co-author Rui Yang, also of JPL, studied a class of organics called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. PAHs are common both on Earth — in candle soot and car exhaust, for example — and in space, having been spotted on comets and asteroids and in the planet-forming disks swirling around newborn stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists mimicked the environment PAHs would experience in the quiet spaces between stars, where the molecules have also been detected. They exposed PAHs to temperatures as low as minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 268 degrees Celsius), bombarded the compounds with ultraviolet radiation similar to that thrown off by stars and used a laser system to identify the products of the resulting chemical reactions.

More complex organics

The researchers found that the PAHs had been transformed. The molecules incorporated hydrogen atoms into their structure, becoming more complex organics — a step along the path toward amino acids and nucleotides, the raw materials of proteins and DNA, respectively.

"PAHs are strong, stubborn molecules, so we were surprised to see them undergoing these chemical changes at such freezing-cold temperatures," Gudipati said.

The study may also help explain why PAHs — which are pervasive throughout the cosmos as gases and on hot dust particles — have not yet been found on ice grains in space. They may be chemically transformed into other complex organics shortly after adhering to the frigid grains, researchers said.

The results are reported in the September issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.