Atom Smasher Won't Create Planet-Eating Black Hole, Court Says

A woman concerned that the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) will create black holes and destroy the Earth lost a court appeal to shut the atom smasher down on Tuesday.

According to Phys Org, a higher administrative court in Muenster, Germany, rejected the German citizen's claims that the LHC, as it is known, will destroy the planet. The woman's attempts have also been rejected by a court in Switzerland.

"In view of the CERN safety reports for the years 2003 and 2008, a hazard of the proton accelerator LHC according to the state of science is impossible," writes the Justice Ministry of north Rine-Westphalia, translated from German by Google. (The LHC is located at the European Center for Nuclear Research, or CERN.)

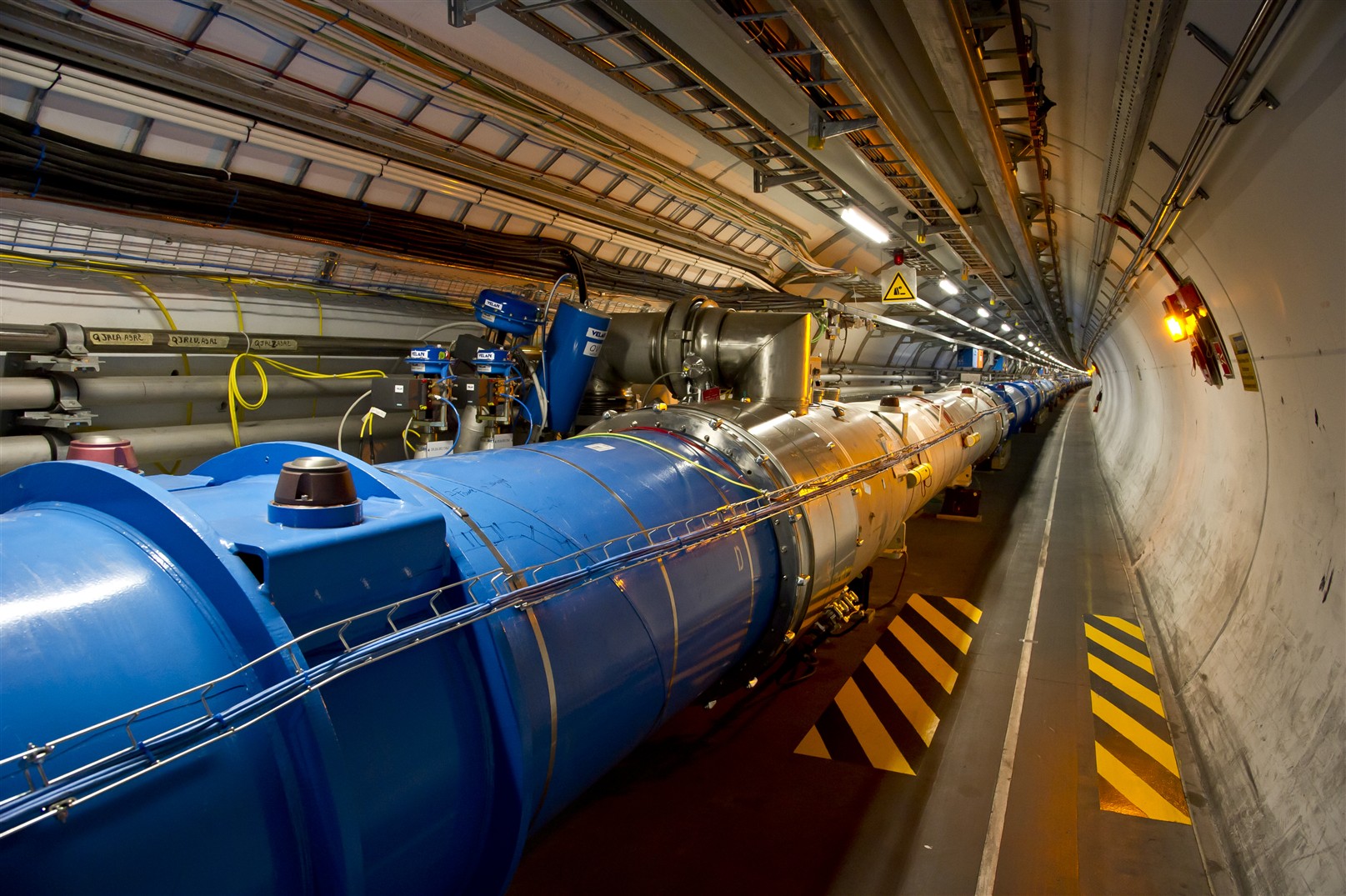

The LHC sits on the border between France and Switzerland. It consists of a 17-mile- (27-kilometer)-long underground ring lined with more than 9,000 magnets designed to smash particles together at high speeds. The purpose is to solve mysteries about the Big Bang, the origins of mass, and other basic physics questions. Most recently, the collider has been in the news for possibly discovering the Higgs Boson, a particle that theoretically gives other particles mass.

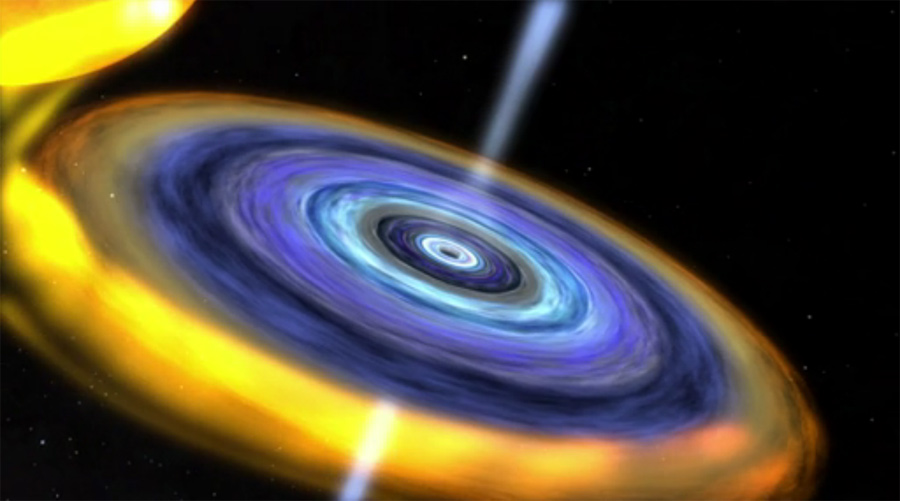

Before the atom smasher whirled to life in 2010, a number of LHC opponents raised fears that the instrument would have catastrophic consequences. A popular notion, that the collider would create mini black holes that would suck up the Earth, has been dismissed by experts as impossible. Even if the collider did manage to create a microscopic black hole, researchers have found that it would evaporate within one-trillionth or one-millionth of a second.

Another theory, that the LHC might produce a strangelet, a theoretical particle that would then convert everything it touched into more strangelets, has been likewise dismissed. Such theories have lost steam in the wake of two years of uneventful research at the LHC.

This story was provided by LiveScience, sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.