Saturn's giant moon Titan glows in the dark like an enormous neon sign, a new study shows.

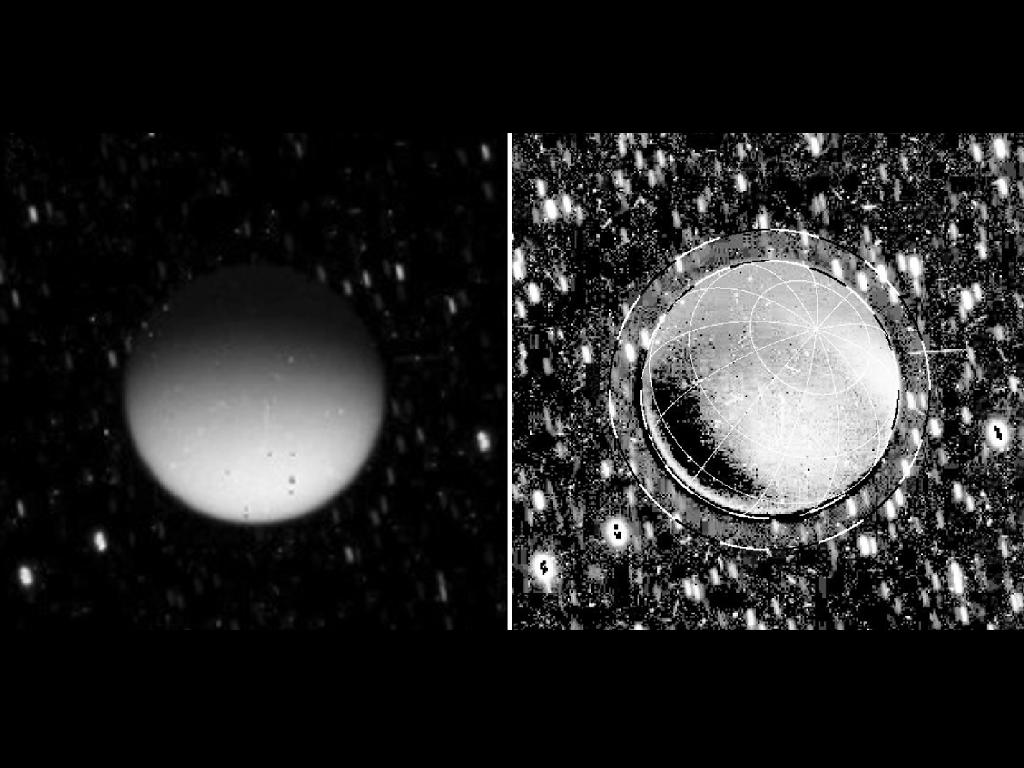

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has spotted a glow emanating from Titan — not just from the top of the moon's atmosphere, but also from deep within its nitrogen-rich haze.

"This is exciting because we've never seen this at Titan before," study lead author Robert West, a Cassini imaging team scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "It tells us that we don't know all there is to know about Titan and makes it even more mysterious."

Titan's homegrown light is exceedingly faint, with an estimated power of a millionth of a watt. An intrepid explorer ballooning through the moon's atmosphere would not be able to see it, researchers said. [Amazing Titan Photos: Saturn's Largest Moon]

Cassini spotted the glow by snapping 560-second-long exposures back in 2009. Titan was passing through Saturn's shadow when the photos were taken, so scientists are confident that the light they're seeing originates from the moon itself.

This light, known as airglow, is generated when atmospheric molecules are excited by sunlight or electrically charged particles, researchers said.

"It's a little like a neon sign, where electrons generated by electrical power bang into neon atoms and cause them to glow," West said. "Here we're looking at light emitted when charged particles bang into nitrogen molecules in Titan's atmosphere."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Cassini team expected to see a glow high in Titan's atmosphere, above 400 miles (700 kilometers) or so. At such altitudes, charged particles from the magnetic bubble around Saturn strip electrons from molecules in the moon's air.

Researchers did indeed see weak emissions at such heights. But they also observed a glow from deeper in the atmosphere — around 190 miles (300 km) — which came as a surprise.

The luminescence originates too far down to be caused by excitation of atmospheric molecules by charged solar particles, researchers said. Their best guess is that the glow is produced by deep-penetrating cosmic rays or by light emitted by a chemical reaction deep in Titan's atmosphere.

Researchers know that Titan's haze harbors all sorts of interesting chemicals, including organic compounds — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it. The moon's glow could help shed light on how these molecules are interacting.

"Scientists want to know what galvanizes the chemical reactions forming the heavy molecules that develop into Titan's thick haze of organic chemicals," said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker, also at the Jet Propulsion Lab. "This kind of work helps us understand what kind of organic chemistry could have existed on an early Earth."

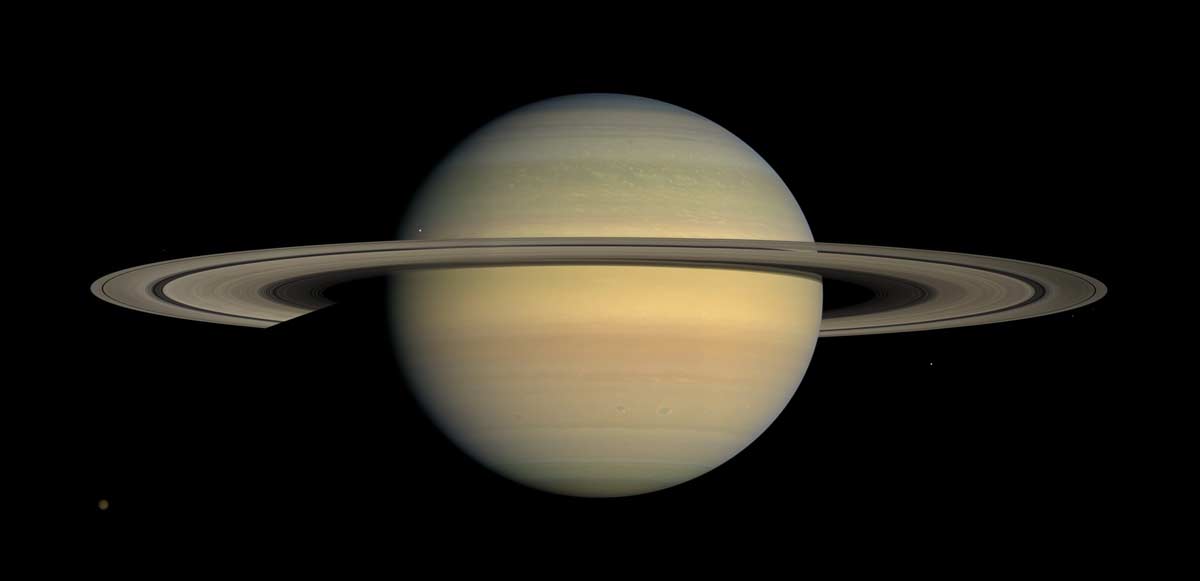

Venus' nightside atmosphere also produces a glow, which is known as the Ashen light. Some scientists speculate that lightning on Venus is responsible. Cassini has detected lightning in Saturn's atmosphere, but it has yet to observe any bolts at Titan, which at 3,200 miles (5,150 km) wide is Saturn's largest moon. The Cassini team will keep looking as it tries to nail down the cause of the moon's mysterious glow.

The new study will be published in an upcoming issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.