How a Real-Life Astrophysicist Found Superman's Planet Krypton: The Inside Story

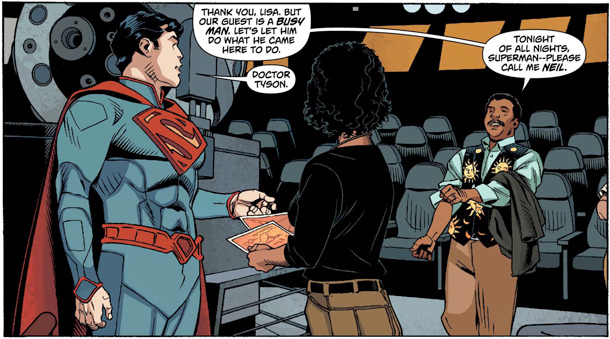

NEW YORK -- Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson just did Superman a super favor.

The scientist, who is director of New York City's Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History, was approached in late summer by DC Comics, home of the long-running Superman series.

Originally, the comic book makers just wanted permission to feature Tyson and the planetarium in an upcoming issue of the series where Superman would view the demolition of his home planet, Krypton, which orbits an alien star named Rao.

"I said, 'Why don't I get you an actual star?'" Tyson told reporters during a meeting Thursday (Nov. 8), the day of the comic book's release.

DC Comics jumped at the chance to infuse real science in the story, and a collaboration was born. [Video: How Neil Tyson Found Superman's Krypton]

"I was proud and honored that our institution could serve this role," Tyson said. "If they're just making stuff up, they don't need us."

Finding the right star

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The real-life star that could play host to fictional planet Krypton must meet certain characteristics. For one, it must be relatively nearby.

The planet is supposed to have self-destructed soon after Superman was born. The infant hero was somehow instantaneously transported to Earth, where he grew up, eventually camouflaging himself as mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. Though Superman made the journey quickly, the light from the destruction of Krypton is just reaching Earth now, Tyson said, when Superman is in his late 20s.

"I thought, 'Let me see if there's a star whose light takes 20-something years to get here,'" Tyson said.

The astronomer looked in a catalog of nearby stars and found a red star at about the right distance: 29 light-years. The star in question is a red dwarf star called LHS 2520 that is cooler and smaller than our sun.

Tyson even approached the International Astronomical Union, the body in charge of official names for astronomical objects, to ask if they would rename LHS 2520 to Rao, in honor of Superman, but he was told no.

Poignant end

Then Tyson was faced with a second challenge. How can Superman view the death of his home planet, when no real-life telescopes are powerful enough to view a planet at such a distance?

After throwing some ideas out that were realistic, but boring (such as having the superhero view data points showing that the light of the host star had stopped diminishing when the planet passed in front of it, signaling the planet's destruction), Tyson and the comic writers settled on a scheme.

To observe the end of Krypton, Superman and the scientists at the Hayden Planetarium create an interferometer — a giant virtual telescope resulting from combining the observations of various telescopes spread out by great distances. ("The word 'interferometer' actually appears" in the comic! Tyson gloated).

To do this, they ask all the world's telescopes to view Krypton at the same time and send their observations back to the planetarium. Then, Superman (using a new power not previously ascribed to him) uses his supercomputer-like internal calculation abilities to combine the data into a single picture of Krypton exploding.

"It's poignant," Tyson said. "The universe is revealing to him what he already knew, but it wasn't real to him until he actually saw it."

Tyson said he was pleased with the finished comic, especially because the artists were able to honor his one request in portraying him. "I said, 'If it makes no difference one way or the other, could you shave a few pounds off me?'" he recalled. "They said, 'Dr. Tyson, these are the comics. Everyone looks good.'"

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.