Warp Speed: What Hyperspace Would Really Look Like

The science fiction vision of stars flashing by as streaks when spaceships travel faster than light isn't what the scene would actually look like, a team of physics students says.

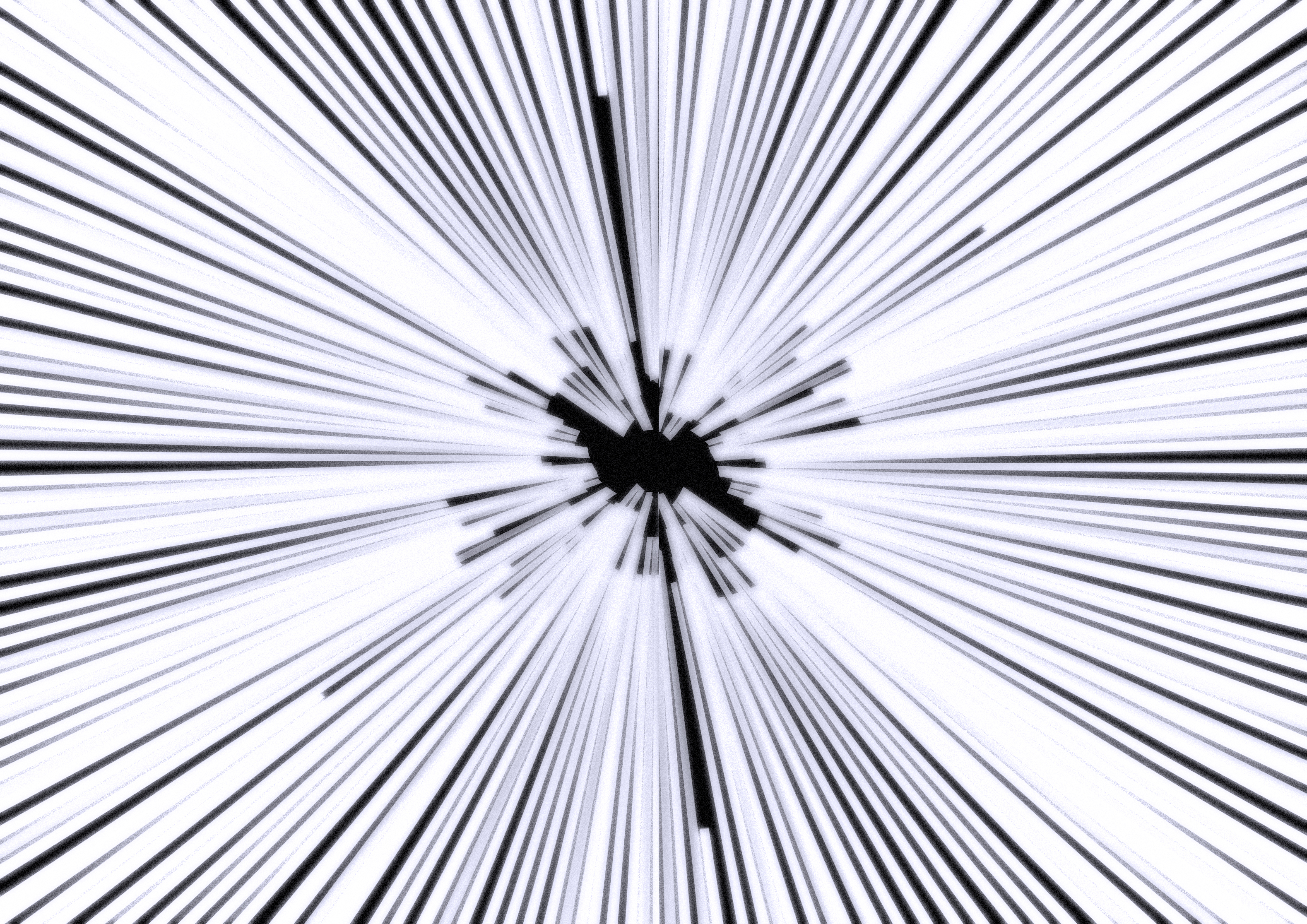

Instead, the view out the windows of a vehicle traveling through hyperspace would be more like a centralized bright glow, calculations show.

The finding contradicts the familiar images of stretched out starlight streaking past the windows of the Millennium Falcon in "Star Wars" and the Starship Enterprise in "Star Trek." In those films and television series, as spaceships engage warp drive or hyperdrive and approach the speed of light, stars morph from points of light to long streaks that stretch out past the ship.

But passengers on the Millennium Falcon or the Enterprise actually wouldn't be able to see stars at all when traveling that fast, found a group of physics Masters students at England's University of Leicester. Rather, a phenomenon called the Doppler Effect, which affects the wavelength of radiation from moving sources, would cause stars' light to shift out of the visible spectrum and into the X-ray range, where human eyes wouldn't be able to see it, the students found. [How Interstellar Space Travel Works (Infographic)]

"The resultant effects we worked out were based on Einstein's theory of Special Relativity, so while we may not be used to them in our daily lives, Han Solo and his crew should certainly understand its implications," Leicester student Joshua Argyle said in a statement.

The Doppler Effect is the reason why an ambulance's siren sounds higher pitched when it's coming at you compared to when it's moving away — the sound's frequency becomes higher, making its wavelength shorter, and changing its pitch.

The same thing would happen to the light of stars when a spaceship began to move toward them at significant speed. And other light, such as the pervasive glow of the universe called the cosmic microwave background radiation, which is left over from the Big Bang, would be shifted out of the microwave range and into the visible spectrum, the students found.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If the Millennium Falcon existed and really could travel that fast, sunglasses would certainly be advisable," said research team member Riley Connors. "On top of this, the ship would need something to protect the crew from harmful X-ray radiation."

The increased X-ray radiation from shifted starlight would even push back on a spaceship traveling in hyperdrive, the team found, slowing down the vehicle with a pressure similar to the force felt at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. In fact, such a spacecraft would need to carry extra energy reserves to counter this pressure and press ahead.

Whether the scientific reality of these effects will be taken into consideration on future Star Wars films is still an open question.

"Perhaps Disney should take the physical implications of such high speed travel into account in their forthcoming films," said team member Katie Dexter.

Connors, Dexter, Argyle, and fourth team member Cameron Scoular published their findings in this year's issue of the University of Leicester's Journal of Physics Special Topics.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct the following error: As an ambulance moves closer to an observer, its wavelength becomes shorter, not longer.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.