How NASA Revealed Sun's Hottest Secret in 5-Minute Spaceflight

While many NASA space telescopes soar in orbit for years, the agency's diminutive Hi-C telescope tasted space for just 300 seconds, but it was enough time to see through the sun's secretive atmosphere.

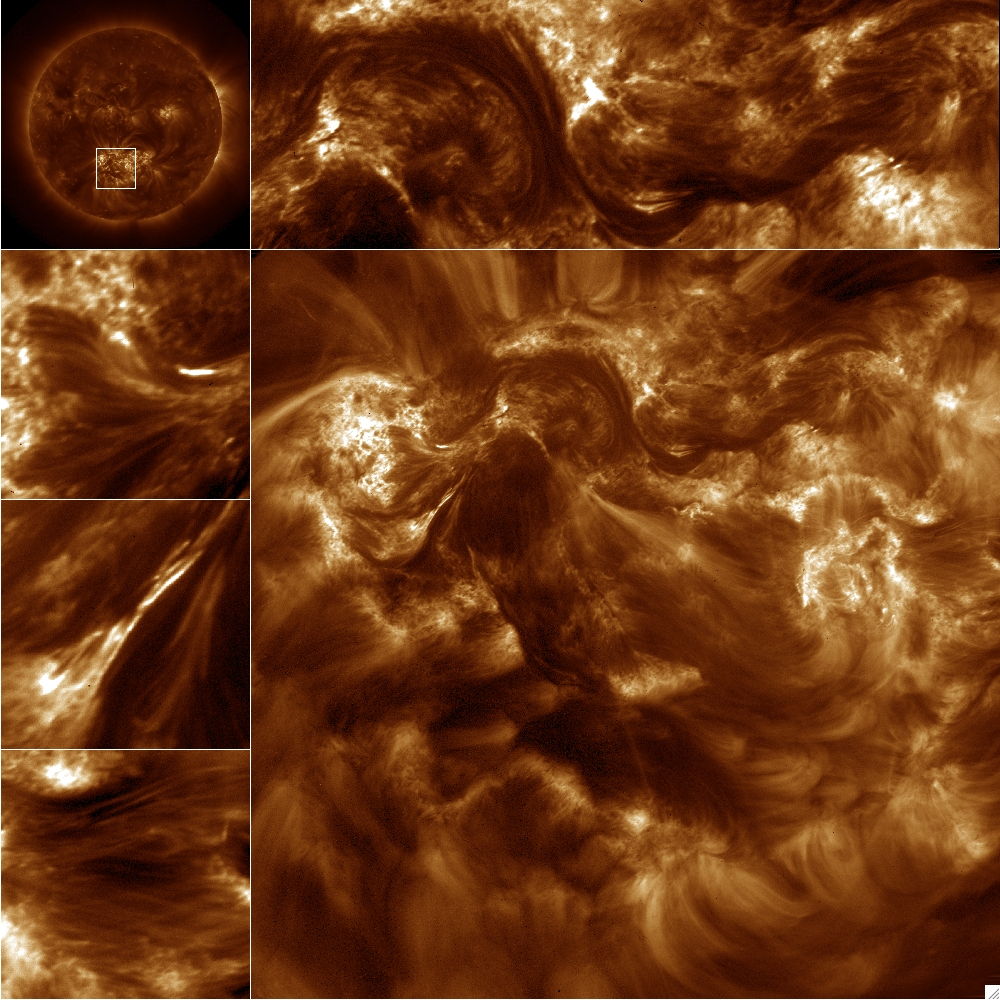

Designed to observe the hottest part of the sun — its corona — the small High-Resolution Coronal Imager (Hi-C) launched on a suborbital rocket that fell back to Earth without circling the planet even once. The experiment revealed never-before-seen "magnetic braids" of plasma roiling in the sun's outer layers, NASA announced today (Jan. 23)

"300 seconds of data may not seem like a lot to some, but it's actually a fair amount of data, in particular for an active region" of the sun, Jonathan Cirtain, Hi-C mission principal investigator at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., said during a NASA press conference today.

The solar telescope snapped a total of 165 photos during its mission, which lasted 10 minutes from launch to its parachute landing.

Hi-C launched from White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico atop a sounding rocket in July 2012. The mission cost a total of $5 million — a relative bargain for a NASA space mission, scientists said. The experiment was part of NASA's Sounding Rocket Program, which launches about 20 unmanned suborbital research projects every year. [NASA's Hi-C Photos: Best View Ever of Sun's Corona]

"This mission exemplifies the three pillars of the [sounding rocket] program: world-class science, a breakthrough technology demonstration, and the training of the next generation of space scientists," said Jeff Newmark, a Sounding Rocket Program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

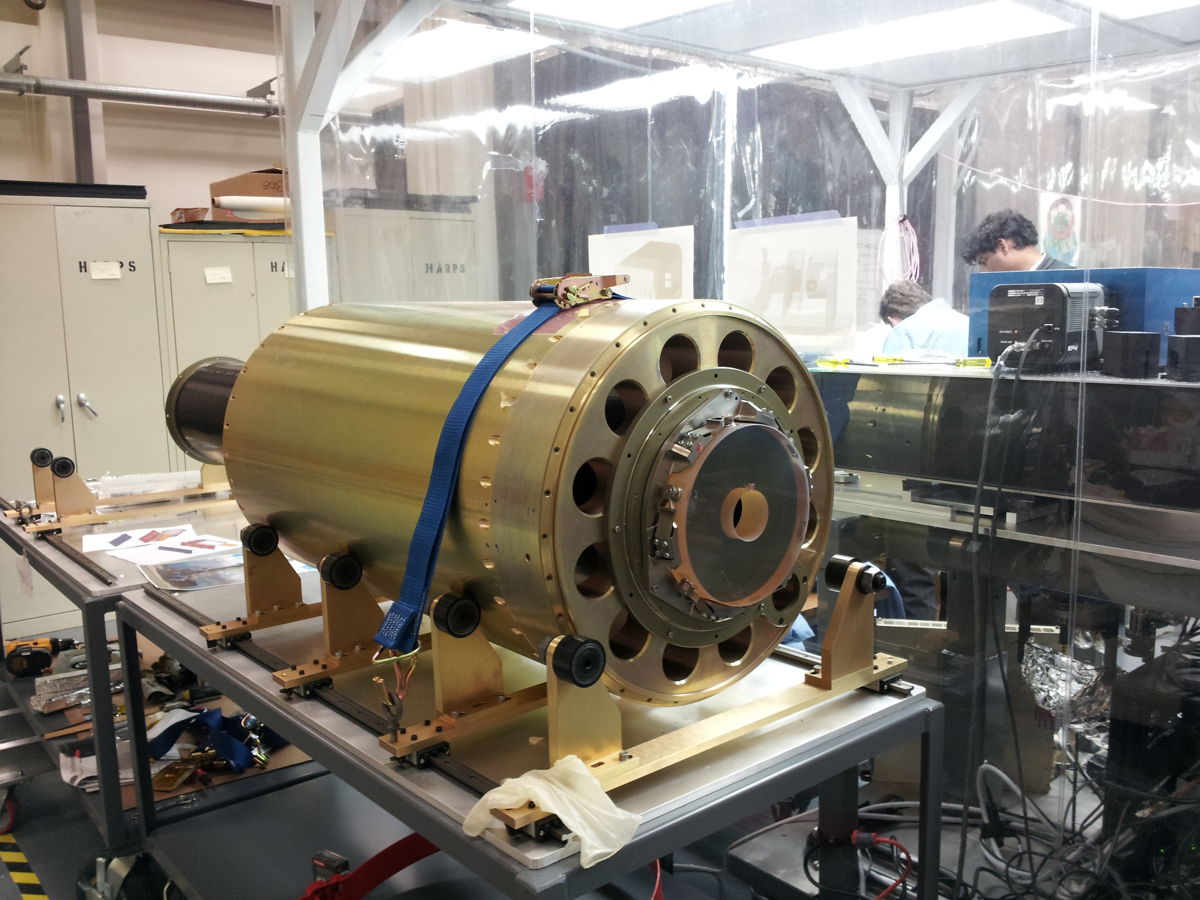

Hi-C used a modified Cassegrain telescope with a 9.5-inch-diameter mirror to take close-up images of an active region on the sun, achieving a resolution equivalent to sighting a dime from 10 miles away.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While NASA already has telescopes in orbit constantly monitoring the whole surface of the sun, such as the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), the Hi-C mission allowed scientists to focus in on a smaller region than SDO is able to.

"SDO has a global view of the sun," Newmark said. "What this research does is act like a microscope and it zooms in on the real fine structure that's never been seen before."

The next step, the researchers said, is to design a follow-up instrument to take advantage of the new telescope technology tested out by Hi-C, to observe for a longer period of time on an orbital mission.

"Now we've proven it exists, so now we can go study it," said Karel Schrijver, a senior fellow at the Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif., where the instrument was built.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.