Are You There, E.T.? SETI Finds No Alien Signals from Exoplanets

Intelligent alien life is likely relatively rare throughout our Milky Way galaxy, with fewer than one in a million solar systems harboring civilizations advanced enough to send out radio signals, a new study reports.

A research team that includes famed alien hunter Jill Tarter — the model for astronomer Ellie Arroway in Carl Sagan's famous book "Contact" — surveyed dozens of planet-hosting stars for radio signals from alien civilizations. They turned up nothing.

"No signals of extraterrestrial origin were found," the researchers conclude in the study, which has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Searching for signs of intelligent life

The team selected 86 stars using data from NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope, and also observed 19 stars that serendipitously fell within range as they searched the primary targets. (One planet candidate turned out to be a false positive, reducing the total number of targets to 104.) [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

The researchers were working with the catalog of Kepler planetary candidates, which at the time included 1,235 possible exoplanets. (That number is now up to 2,740, with 105 of them confirmed to date.)

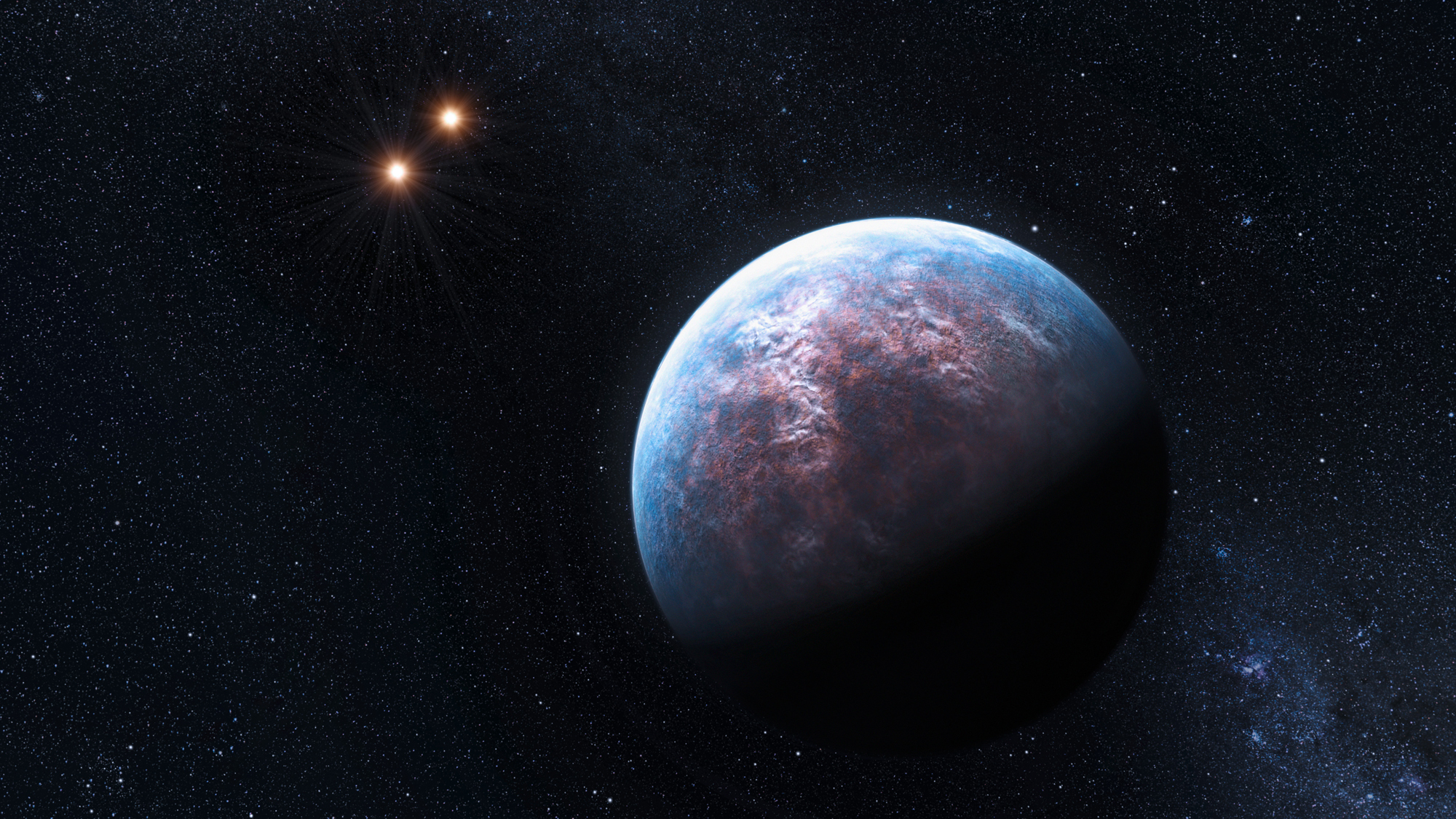

The astronomers limited their search to stars that host five or six planet candidates, some of which reside within the habitable zone — the range of distances from a star where liquid water can exist on a world's surface. The selected stars are about 1,000 light-years to 1,500 light-years from Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Radio signals in narrow, focused bands are a possible indication of intelligent life, given that humans generate such signals here on Earth.

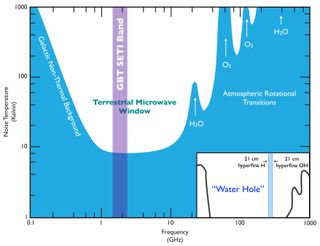

So, using the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the team probed each star system for five minutes between February and April 2011. They examined the planets in a radio-frequency range of 1.1 to 1.9 GHz, which is between the cell phone and television bands used on Earth.

This range of frequencies includes a so-called "watering hole" between 1.4 GHz and 1.7 GHz, where hydrogen and hydroxyl (both components of water) emit signals from quantum processes detectable in radio telescopes.

"The analogy is, it's the water hole where animals go in the desert, so perhaps this band of frequencies is a common gathering place for E.T.," study lead author Andrew Siemion of the University of California, Berkeley, told SPACE.com.

Researchers scrutinized the data for planets transmitting signals in a narrow band of 5 Hz, which is considered too narrow for transmission from a natural source. They came up empty.

One in a million

Based on their findings, the researchers calculated that fewer than one in a million stars in the Milky Way likely harbor a civilization advanced enough to send out detectable signals.

But there could still be millions of civilizations out there waiting to be found, the scientists added, since billions of Earth-like planets are thought to populate the Milky Way.

The team also cautioned that searching for one particular type of signal could have reduced their odds of finding something.

"In particular, we can offer no argument that an advanced, intelligent civilization necessarily produces narrow-band radio emission, either intentional or otherwise," the study states. "Thus we are probing only a potential subset of such civilizations, where the size of the subset is difficult to estimate."

The researchers acknowledged that narrow radio signals are subject to interference from the interstellar medium — a thin gas floating between the stars — and the solar wind, which is a stream of particles coming from the sun. However, they did not foresee these phenomena interfering unduly with their observations in the current study, given the distance of the stellar targets.

The team will use the Green Bank Telescope again to refine their search in the coming months, looking particularly at stars that have two planets aligning in relation to Earth. The scientists hope to listen in as the planets communicate with each other, if the planets are transmitting signals in the first place.

They also plan to "piggyback" on regular observations by the telescope to automatically monitor for signals as other science teams do separate investigations.

This was the first time the telescope was used for such alien-hunting work, Siemion added. In the future, more sensitive radio telescopes, such as the Square Kilometer Array, might be able to find even weaker signals than we can detect now, he said.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.