Russian Meteor Fallout: Military Satellite Data Should Be Shared

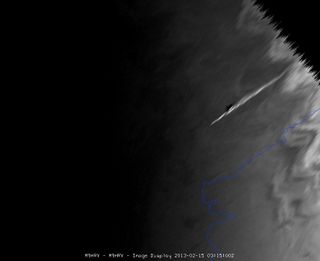

Piecing together the true nature of the meteor that detonated over Russia would benefit by observations likely gleaned by U.S. military spacecraft.

But for several years, that data has been stamped classified and not made available to the scientific community that study near-Earth objects (NEOs) and any potential hazard to Earth from these celestial interlopers.

In the wake of the Russian meteor explosion, there is a renewed call to make data gathered by both space systems and ground networks speedily available to scientists.

Incoming meteoroids

"The satellites that monitor the skies around the world for missile launches also detect brilliant incoming meteoroids, including startling events much smaller than the Chelyabinsk bolide," said asteroid expert Clark Chapman of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

This type of information is extremely valuable for helping scientists understand the potentially dangerous cosmic environment of planet Earth, Chapman told SPACE.com. [See video of the Russian meteor explosion]

"In the past, these data have been partly withheld from the scientific community. They should be released immediately, while scientists, emergency management officials, and others are trying to understand what has happened, where people might have been hurt, and where valuable meteorites might befound," Chapman emphasized.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

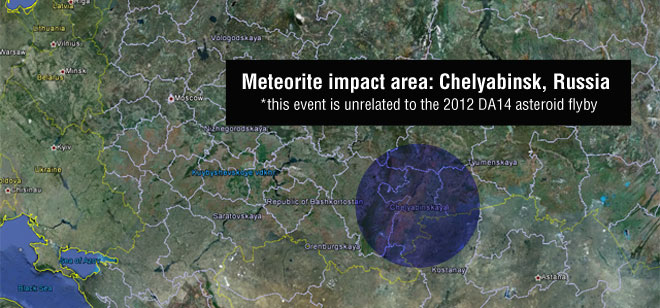

More than 1,000 people were injured and thousands of buildings were damaged during Friday's meteor blast over the city of Chelyabinsk near the Ural Mountains. The explosion was caused by an airburst of a 55-foot (17 meters) space rock that weighed 10,000 tons and detonated in the atmosphere while traveling at about 40,000 miles per hour (64,373 km/h).

Data sharing

The Russian fireball detonation was "Mother Nature at her surprising best!" That's the view of Apollo astronaut Russell Schweickart, Chair Emeritus of the B612 Foundation of Mountain View, Calif.

B612 is a group dedicated to harnessing the power of science and technology to protect the future of planet Earth while extending humankind's reach into the solar system.

Schweickart also calls attention to the value of military satellite data to better assess the Russian meteor and other space rock events that pierce the Earth’s atmosphere.

"There's no question that data sharing here is critical," Schweickart said.

"We need to learn as much as possible from these incidents, and without jeopardizing any legitimate national security consideration, what they have should openly be shared with the rest of us," he told SPACE.com. [See more photos of the Russian meteor blast]

Meteor airburst events

The call for release of military fireball data was flagged in a 2010 National Research Council report, "Defending Planet Earth: Near-Earth Object Surveys and Hazard Mitigation Strategies."

A blue-ribbon committee of experts found that "U.S. Department of Defense satellites have detected and continue to detect high-altitude airburst events from NEOs entering Earth’s atmosphere. Such data are valuable to the NEO community for assessing NEO hazards."

Furthermore, the NRC study group recommended: "Data from NEO airburst events observed by the U.S. Department of Defense satellites should be made available to the scientific community to allow it to improve understanding of the NEO hazards to Earth."

The report went on to note that airbursts are also detected by the arrays of microbarographic sensors deployed by the DoD and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) Organization.

This international network — called the International Monitoring System — consists of seismic, infrasound, radionuclide, and hydroacoustic stations. However, the data are not publicly available and the scientific community would benefit from unfiltered access to the data produced by these arrays, the report said.

In an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) symposium held Feb. 17 during the organization's annual meeting in Boston, experts took part in a session entitled "Unreasonable Usefulness of Test-Ban Verification for Disaster Warning and Science."

According to the AAAS, the multidisciplinary verification regime of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, developed over five decades ago, today consists of seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound, radionuclide, and onsite inspection technologies that have matured into the world's most sophisticated multilateral monitoring network.

The network consisting of 337 facilities around the globe — of which 85 percent are already in operation — is sending around 10 gigabytes of data daily in near real time.

These data are available to all 183 CTBT member states. However, according to the AAAS, science is only beginning to discover the value of this $1 billion system for uses beyond the detection of nuclear tests. The data are an untapped wealth of potential.

Possible uses include the monitoring and studying of meteors entering the atmosphere, climate change, as well as volcanic eruptions, even whale singing/migrating and icebergs calving.

Interesting insight

Because of its intense power, the Russian meteor explosion was detected by seismometers around the Ural region, including those that are part of the Global Seismographic Network, said AAAS symposium participant Miaki Ishii, associate professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences within Harvard University’s Seismology Group in Cambridge, Mass.

"For example, stations at Arti, Russia and Borovoye, Kazakhstan show a few millimeters of ground displacement," Ishii told SPACE.com.

"I'm sure careful analysis of these data will provide interesting insight into the event. There are classified data that would certainly be useful in scientific studies, especially from regions where we have limited amount of data," Ishii said.

Monitoring our planet: all the time

Adding his voice to data sharing and the Russian meteor event is Raymond Jeanloz, professor of astronomy and Earth and planetary science at the University of California at Berkeley, also a participant in the AAAS symposium.

"Yes, I think this is an excellent example of how useful it is to have multiple sensors monitoring our planet everywhere, all the time, including the infrasound and seismic components of the CTBTO's International Monitoring System, as well as satellites and telescopes," Jeanloz said.

"Further analysis is needed, but it looks like this was an event with about 100-200 kiloton explosive yield, a rough estimate that needs confirming and refining," Jeanloz said, "meaning that it happens on time periods of decades to perhaps a century or so."

In fact, NASA's most recent estimate has pegged the Russian meteor blast as the equivalent of a 500-kiloton explosion.

Jeanloz said that there are possibilities of enough advance warning being feasible to identify location and time of impact for future meteor events, perhaps with enough accuracy for useful evacuation. Networking more sensors and infrastructure would be needed, he said, but this would be using current technology.

Regarding last week's Russian bolide, Jeanloz told SPACE.com, it is of interest as a hazard to be mitigated, and also in terms of basic science. These objects coming in from space, he said, "represent the last few crumbs of materials" that built our planet.

"We're still in the tail end of Earth's formation 4.5 billion years after the main event! We are only recently learning about the statistics of such bolides — how frequently they intersect Earth, as a function of size and therefore explosive power on impacting Earth's surface or atmosphere — because it is only in recent years that we have good global coverage of such events," Jeanloz concluded.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the meteor size estimate by NASA, which is 55 feet (17 meters).

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.