NASA Discovers New Radiation Belt Around Earth

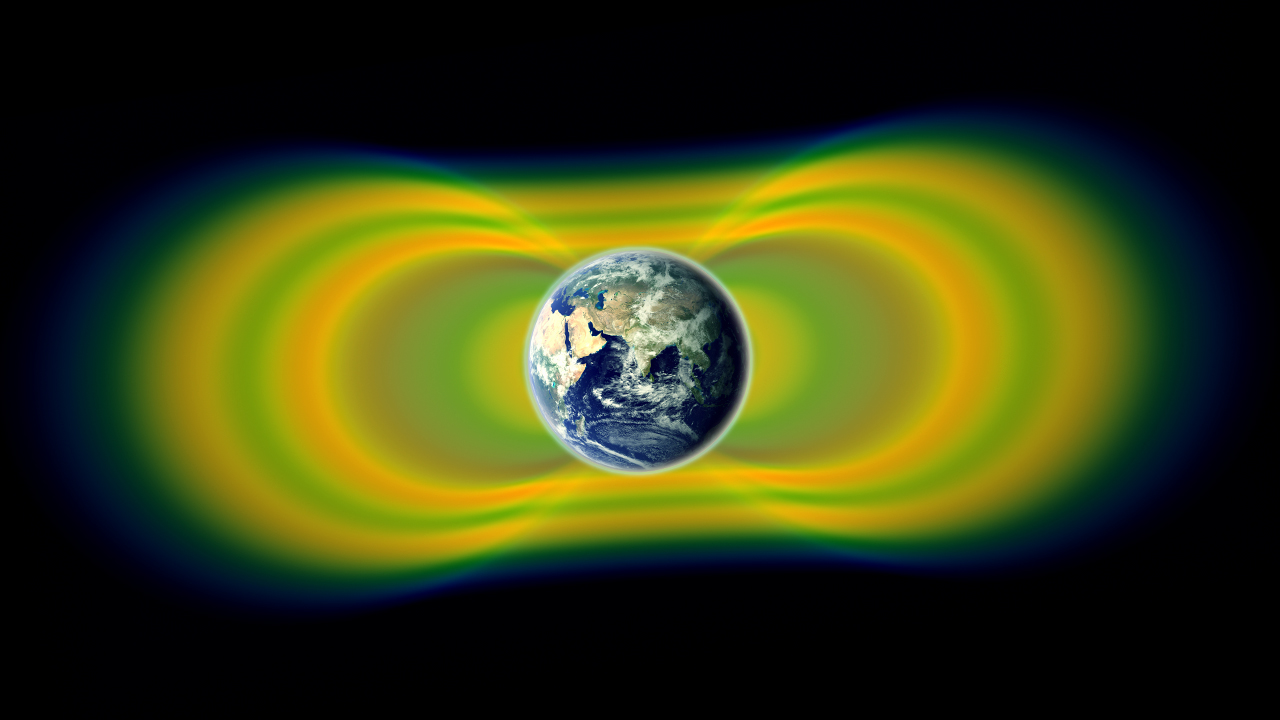

A ring of radiation previously unknown to science fleetingly surrounded Earth last year before being virtually annihilated by a powerful interplanetary shock wave, scientists say.

NASA's twin Van Allen space probes, which are studying the Earth's radiation belts, made the cosmic find. The surprising discovery — a new, albeit temporary, radiation belt around Earth — reveals how much remains unknown about outer space, even those regions closest to the planet, researchers added.

After humanity began exploring space, the first major find made there were the Van Allen radiation belts, zones of magnetically trapped, highly energetic charged particles first discovered in 1958.

"They were something we thought we mostly understood by now, the first discovery of the Space Age," said lead study author Daniel Baker, a space scientist at the University of Colorado.

These belts were believed to consist of two rings: an inner zone made up of both high-energy electrons and very energetic positive ions that remains stable in intensity over the course of years to decades; and an outer zone comprised mostly of high-energy electrons whose intensity swings over the course of hours to days depending primarily on the influence from the solar wind, the flood of radiation streaming from the sun. [How NASA's Twin Radiation Probes Work (Infographic)]

The discovery of a temporary new radiation belt now has scientists reviewing the Van Allen radiation belt models to understand how it occurred.

Radiation rings around Earth

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The giant amounts of radiation the Van Allen belts generate can pose serious risks for satellites. To learn more about them, NASA launched twin spacecraft, the Van Allen probes, in the summer of 2012.

The satellites were armed with a host of sensors to thoroughly analyze the plasma, energetic particles, magnetic fields and plasma waves in these belts with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution.

Unexpectedly, the probes revealed a new radiation belt surrounding Earth, a third one made of super-high-energy electrons embedded in the outer Van Allen belt about 11,900 to 13,900 miles (19,100 to 22,300 kilometers) above the planet's surface. This stable ring of space radiation apparently formed on Sept. 2 and lasted for more than four weeks.

"The feature was so surprising, I initially foolishly thought the instruments on the probes weren't working properly, but I soon realized the lab had built such wonderful instruments that there wasn't anything wrong with them, so what we saw must be true," Baker said.

This newfound radiation belt then abruptly and almost completely disappeared on Oct. 1. It was apparently disrupted by an interplanetary shock wave caused by a spike in solar wind speeds.

"More than five decades after the original discovery of these radiation belts, you can still find new unexpected things there," Baker said. "It's a delight to be able to find new things in an old domain. We now need to re-evaluate them thoroughly both theoretically and observationally."

A radiation mystery

It remains uncertain how this temporary radiation belt arose. Van Allen mission scientists suspect it was likely created by the solar wind tearing away the outer Van Allen belt.

"It looks like its existence may have been bookended by solar disturbances," Baker said.

Future study of the Van Allen belts can reveal if such temporary rings of radiation are common or rare.

"Do these occur frequently, or did we get lucky and see a very rare circumstance that happens only once in a while?" Baker said. "And what other unusual revelations might come now that we are really looking at these radiation belts with new, modern tools?"

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 28 in the journal Science.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us