8 Cool Facts About the ALMA Telescope

Introduction

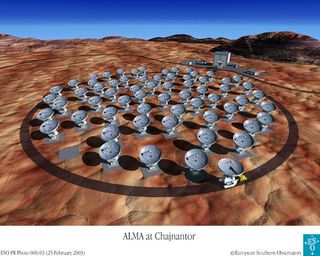

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) is the world's most powerful observatory for studying the universe at the long-wavelength millimeter and submillimeter range of light. It's designed to spot some of the most distant, ancient galaxies ever seen, and to probe the areas around young stars for planets in the process of forming.

The opening of the telescope array is being celebrated in an inauguration ceremony on Wednesday (March 13) at its observation site in Chile's Atacama desert. Here are six things you should know about the ambitious, not to mention immense, astronomy project.

It is ginormous

ALMA combines the forces of 66 radio antennas, most almost 40 feet (12 meters) in diameter, to create images comparable to those that could be obtained with a single 46,000-foot-wide (14,000 meters) dish. The observatory is accurate enough to discern a golf ball 9 miles (15 kilometers) away.

A decade to build

The telescope is a collaboration of four continents, being sponsored by countries in North America, Europe and East Asia, with the cooperation of Chile. Planning and constructing the observatory took thousands of scientists and engineers from around the world more than 10 years.

ALMA is one high eye on the sky

The observatory is among the highest instruments on Earth, at an altitude of 16,570 feet (5,050 meters) above sea level. Its perch high atop the Chajnantor plateau puts it above much of the Earth's atmosphere, which blurs and distorts light.

It's in the driest place on Earth

ALMA's location in Chile's Atacama desert, the driest place in the world, means almost every night is clear of clouds and free of light-distorting moisture. Some weather stations in the desert have never received rain, and scientists think the Atacama got no significant rainfall between 1570 and 1971. [10 Driest Places on Earth]

ALMA dishes are nearly perfect

The surfaces of its dozens of radio dishes are almost perfect, with none deviating from an exact parabola by more than 20 micrometers (20 millionths of a meter, or about 0.00078 inches). This prevents any incoming radio waves from being lost, so that the resulting picture captures as much distant cosmic light as possible. The radio dishes, which weigh about 100 tons each, are made of ultra-stable CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic) for the reflector base, with reflecting panels of rhodium-coated nickel.

This is one cool telescope — literally

The electronic detector called the "front end" that amplifies and converts the radio signals collected at each ALMA antenna must be kept at a chilling 4 Kelvin ( minus 452 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 269 degrees Celsius), to prevent introducing noise to the signal.

It's costs a pretty penny

The ALMA observatory cost $1.3 billion to construct, with the price tag being split by the three sponsoring regions: North America, Europe and East Asia. Of the total cost, about $500 million was contributed by U.S. taxpayers.

ALMA will look in long-wavelength light

ALMA will look at the skies in millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths (submillimeter light has slightly shorter wavelengths than millimeter light, whose wavelengths are measured in the millimeters). These ranges fall along the boundary between the radio and microwave bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, and have longer wavelengths than optical light. This band of light allows astronomers to probe into the dark cores of gas clouds to study star and planet formation, and to see extremely distant light that's been shifted toward the red end of the spectrum.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.