After Finding Mars Was Habitable, Curiosity Rover to Keep Roving

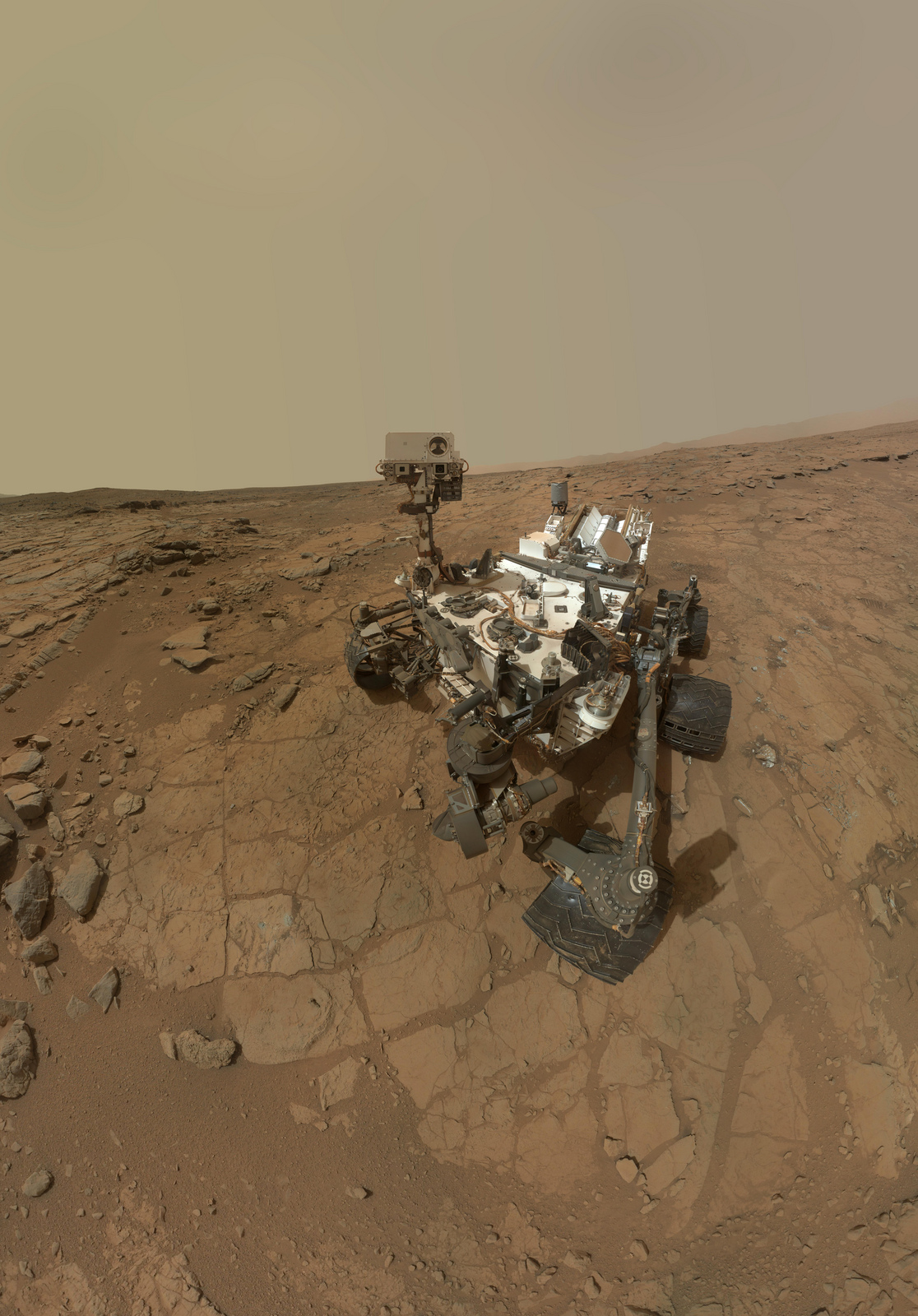

WASHINGTON — NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has already achieved its main mission goals, just seven months after landing on the Red Planet, but the car-size robot has no plans to rest on its laurels.

Curiosity's chief task when it landed last August was to determine if Mars could have ever hosted microbial life. The rover's observations show that Mars was indeed habitable long ago, when the planet was warmer and wetter, scientists announced Tuesday (March 12).

Curiosity has also discovered an ancient streambed where water flowed for thousands of years at a time. And the rover has done all of this while putting only about a third of a mile on its odometer.

"The mission has accomplished its goals seven months into a two-year mission," Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena, said during a public lecture here Tuesday at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, just hours after the Curiosity team announced its latest discovery. [The Search for Life on Mars (Photo Timeline)]

But the mission isn't over yet. The Curiosity team intends to spend the remainder of the rover's time in search of other areas where ancient life could have thrived, if it ever evolved on Mars. In the meantime, the rover is taking a short break from science while it rests in safe mode following a minor computer glitch. Grotzinger said on Monday (March 18) that he expects Curiosity to be back to its science operations in a couple of days.

Landing the rover

During his talk, Grotzinger outlined some of the mission's highlights to a crowd of children and adults.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

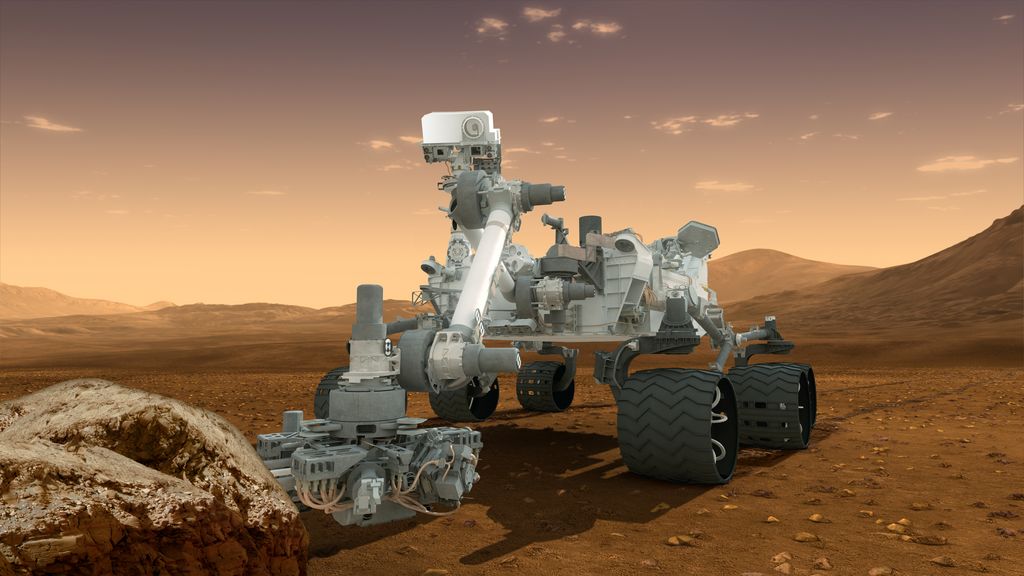

"[Curiosity] is built on the tradition of previous rovers," Grotzinger said as he reviewed the 10 different science instruments on the traveling laboratory.

As part of its "seven minutes of terror" landing inside Mars' huge Gale Crater, the rover's descent craft employed rocket thrusters to slow it from 13,000 mph (21,000 kh/h) to a hovering stop. A sky crane then lowered the rover to the ground to keep the thrusters from destroying the landing site or covering the craft with dust, which would have rendered Curiosity inoperable.

Despite these precautions, the force from the Mach 7 thrusters still showered a small amount of dirt and pebbles onto the rover, though Curiosity survived pretty much unscathed. (However, the debris did apparently damage one of the rover's two wind sensors). Grotzinger lauded the decision to use the innovative method, based on that bit of dirt.

"We're really glad we didn't land the rover without the skyhook," he said.

Once Curiosity touched down at Bradbury Landing, it was time to take a look around. Using its Mast Camera, the rover took images of the panorama on all sides, providing a stunning look at Mars.

"It's just a scenically beautiful field area, because wherever you look, you're surrounded by mountains," Grotzinger said. [Curiosity's Latest Mars Photos (Gallery)]

A new lifestyle

The distance to Mars means that NASA engineers can't control the rover in real time. It takes 14 minutes for signals to travel from Earth to the Curiosity rover, which means that the robot's team must plan all maneuvers in advance.

"The one thing we don't do is joystick it," Grotzinger said. "It's not an Xbox game."

Instead, the team sends two sets of instructions each day, one in the morning and one in the evening.

"We don't text, we email," Grotzinger said.

Nor do Curiosity's pilots send the directions blindly, with no idea of how the rover might respond. Engineers first perform a run-through on an Earthbound test version of Curiosity, nicknamed Scarecrow, Grotzinger added.

At 24 hours, 39 minutes, the Martian day is slightly longer than Earth's, presenting an additional challenge for those working on the expedition. The rover team initially had to adjust their schedules to work on Mars time.

According to Grotzinger, the ideal would be for everyone to stay up 39 minutes longer each day, gradually shifting their times to coincide with sunrise and sunset on the Red Planet.

"Nobody actually does that," Grotzinger said, explaining that most people would instead power through the longer schedules, then crash.

"You're like vampires," he added.

The shift schedule also complicates efforts to spend time with family and friends.

Gradually, the scheduled has shifted so that team members work 10-hour days instead. Sundays have dropped off the schedule, and Saturdays will soon follow, leaving Curiosity's team with a five-day work week.

'A little waylaid'

After making sure Curiosity's wheels and assorted motors were working properly, the team sent the rover off on its first big drive — in the opposite direction of its ultimate destination, a specific Martian mountain.

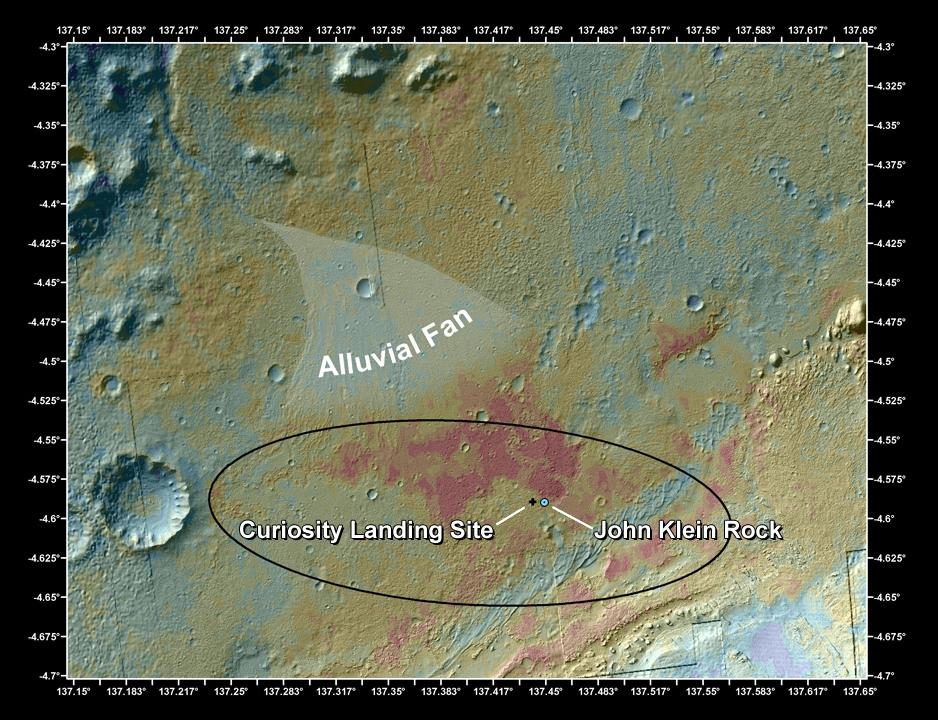

Scientists on Earth had originally targeted Mount Sharp, which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) from Gale Crater's center, as a potential source for unraveling the geological history of Mars. As the rover travels up the mountain, samples taken from the changing terrain should provide insight into the planet's different epochs.

But studying a map of where the rover touched down, the scientists noticed an interesting feature.

"We got a little waylaid by something we found in the landing ellipse," Grotzinger said.

On Earth, deposits of sediments known as alluvial fans indicate paths where water sometimes flows downhill. Researchers spotted what appeared to be an alluvial fan near where Curiosity landed, separated from the rover by a patch of red, heat-radiating rocks.

The scientists still aren't sure what causes the rocks' unusual features, which are visible to orbiters at night.

"We had a hunch that maybe it had something to do with water," Grotzinger said.

Before heading to Mount Sharp, therefore, the team decided to drive in the opposite direction, toward the fan and other intriguing features, where Curiosity would ultimately take its first soil sample.

The complete, 180-degree change of direction was possible because Curiosity is a "discovery-driven mission," Grotzinger said.

A working trip

Curiosity's journey took it toward a junction of three different terrains, which the mission team dubbed Glenelg. Along the way, the 1-ton robot rolled through an ancient streambed.

"This is the oldest streambed you will ever see in your life," Grotzinger told the audience as he showed an image of the roughly 3.5-billion-year-old remnant, which the team announced in late September. Although scientists have previously identified signs of flowing water on Mars, Curiosity found a formation that bore a strong similarity to streambeds on Earth. [The Search for Water on Mars (Images)]

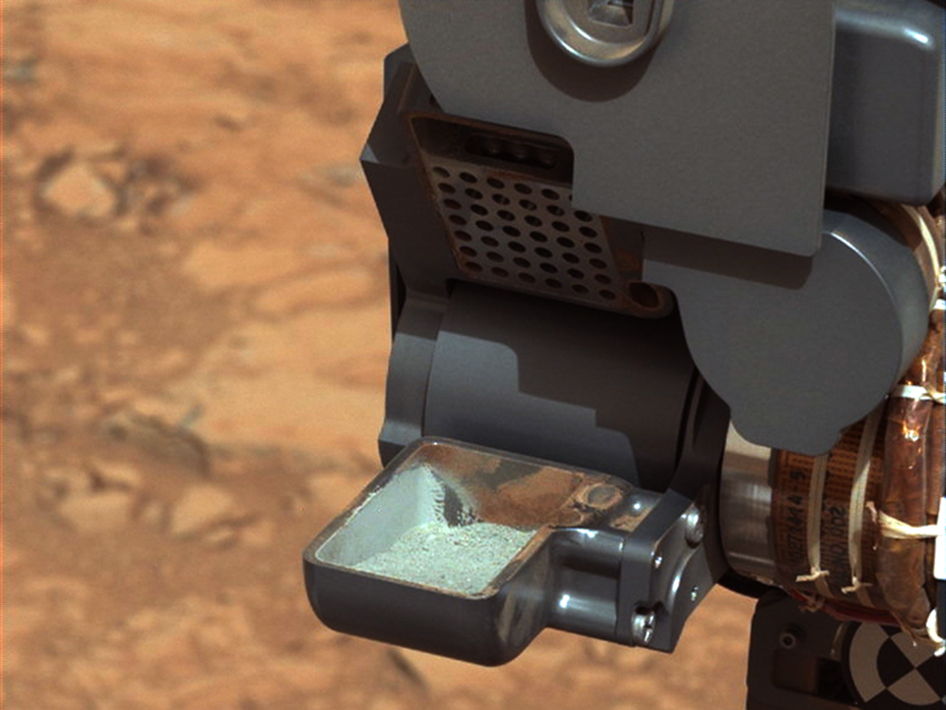

The rover then stopped at a small dune dubbed Rocknest to take its first soil sample. Curiosity used some dirt to clean out its sample-handling system before passing a sample into its Chemistry and Mineralogy, or CheMin, instrument.

"This was a big moment for us, because it had never been done before on another planet," Grotzinger said.

Grotzinger described how Curiosity's huge robotic arm — "think of it as a giant Swiss Army knife" — scooped the samples from the small dune. The arm then vibrated to level out the heaping sample. Curiosity then deposited the sample inside of its body and sifted out the larger material using what Grotzinger describes as "tai-chi-like motions that allow the powder to pass through the sieve."

CheMin then passed X-rays through the aspirin-sized sample to reveal the minerals contained within. Though exciting, the results of the first X-ray diffraction performed on another planet were not surprising, revealing minerals already known to be common on the Red Planet. But the test confirmed that all of the instruments were working.

The sample was then placed inside of the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument. SAM heated the soil and watched for volatile gases steaming off of it. The gases move through SAM, which is actually made up of several miniaturized instruments.

"Shunting around all of these different gases is key for SAM," Grotzinger said.

SAM found traces of simple, chlorine-containing organic compounds in the Martian soil, though the team has yet to rule out the possibility of contamination from Earth.

'A very habitable place'

Curiosity then rolled onto an outcrop called John Klein. After surveying the site, the team selected a small sample rock for drilling.

"Being a first-time activity, we got the safest thing that [the engineers] felt comfortable with," Grotzinger said.

In early February, Curiosity drilled 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) into the rock, marking the first time a robot had collected samples from the interior of a Red Planet rock. But although the rock's surface appeared red, the dust that came out was not.

"We got really excited right off, because the color [of the rock dust] was green," Grotzinger said, adding that this hue implied that the interior of the rock might not be oxidized like the surface of the planet.

After it was sieved and X-rayed, the new sample revealed phyllosilicates, clay minerals that contain water in their structure. CheMin and SAM also revealed several chemicals considered important for life, leading to this week's big announcement.

"We would guess that if micro-organisms ever evolved on Mars, they would thrive here," Grotzinger said.

Although Curiosity has met its mission objectives, its work on Mars is far from finished. The science team hopes to locate other sites that were once habitable in the Red Planet's past. Grotzinger emphasized that Curiosity is not a life-finding mission and is incapable of detecting either living microbes or fossils. But it can find environments conducive to life.

"What we need now is to find water on Mars that has the right chemistry for micro-organisms," Grotzinger said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd