Hyperion: Saturn's Spongy Moon

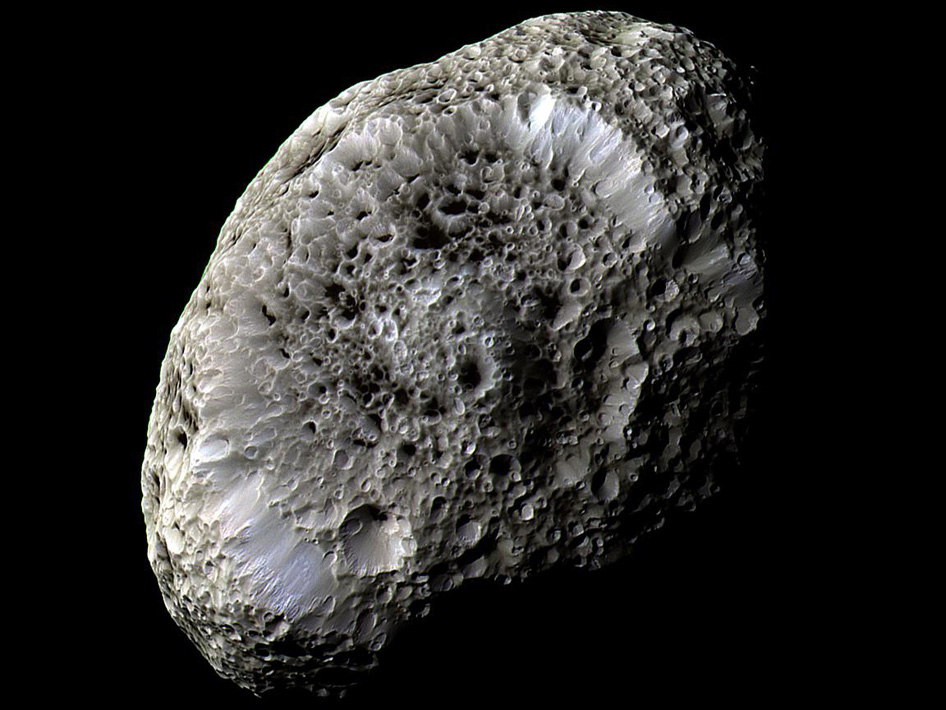

Saturn's porous moon, Hyperion, is the largest known nonspherical moon in the solar system. The potato-shaped satellite has a constantly changing chaotic rotation, with tugs from the nearby moon, Titan, keeping Hyperion from a circular orbit.

Hyperion blasted the Cassini spacecraft with static electricity during a close flyby in 2005, according to a study that reanalyzed the data in 2014. This was a surprise; because the moon is so small, it wasn't thought to have any appreciable interaction with Saturn's magnetosphere (magnetic environment). The results showed that the surface has a strongly negative surface potential. While Cassini emerged from the encounter with no detected effects, scientists noted this phenomenon should be studied closely to protect future spacecraft.

Discovery and naming

The odd moon was first discovered in 1848 by two independent groups. English astronomer William Lassell spotted the moon two days after fellow American father-and-son team William and George Bond. All three men are credited with the discovery.

The last of the eight major satellites to be discovered, Hyperion was found just after English astronomer John Herschel suggested the moons around the ringed planet be named for the Titans. These mythical beings, later overthrown by the Olympian gods, were the brothers and sisters of the Greek god Cronus, known to the Romans as Saturn. Hyperion, Saturn's elder brother, was the god of watchfulness and observation.

The path around the planet

Hyperion differs from most moons because it is not a spheroid. The potato-shaped satellite has three axes, which are 255 by 163 by 137 miles (410 by 260 by 220 kilometers), making it the largest known irregular-shaped moon in the solar system. Early in its history, Hyperion may have been a larger, more spherical satellite that suffered a major impact.

One of the few major moons that doesn't keep one face perpetually turned toward Saturn, Hyperion spins approximately once every 13 days on its 21-day trip around the planet. However, its odd shape keeps it from a predictable rotation. When NASA's Cassini mission visited the moon, its ever-changing rotation kept scientists from predicting what part of the moon it would see.

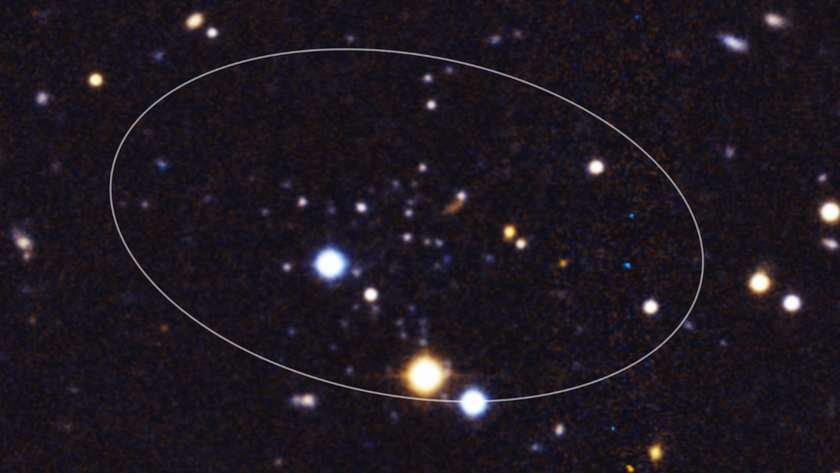

Traveling around Saturn in an eccentric (noncircular) orbit, Hyperion keeps an average distance of 932,637 miles (1,500,934 km) from the planet. Its close orbit with Saturn's largest moon, Titan, allows gravity to cause the two to speed up and slow down as the distance between them shifts.

Saturn's spongy moon

Slightly more than half as dense as water, Hyperion's composition is still a mystery. Porous water ice may account for the difference, as could the inclusion of lighter materials such as frozen methane or carbon dioxide. The existence of such materials would be consistent if a number of smaller ice and rock bodies had drawn together, or accreted, to form the moon, making Hyperion similar to a rubble pile. An example: A 2012 Icarus study of the surface suggests Hyperion is mostly made up of water ice with some "additional materials", such as carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide does not appear to be pure ice, but a more complex structure such as a clathrate (where molecules of one substance are trapped inside the ice of another).

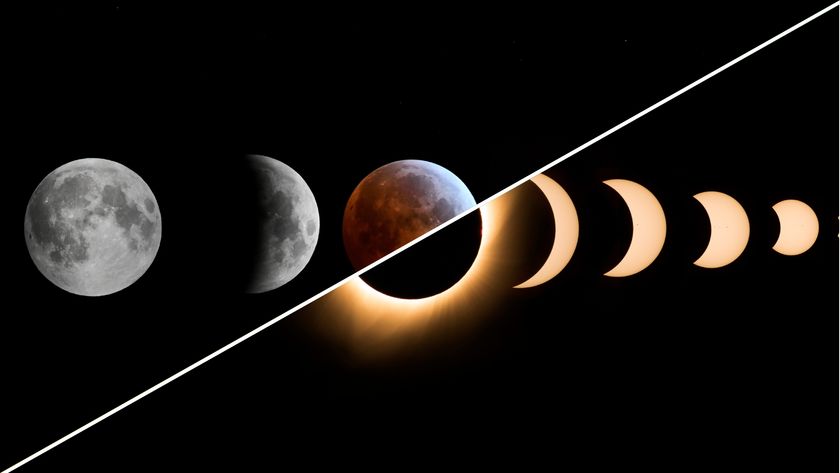

The surface of the satellite is heavily cratered, much like Phoebe and Iapetus. Traveling so far from Saturn, the three distant moons show more signs of bombardment than their closer companions. Tidally heated by the huge planet, ice on the closer moons may have melted and smoothed over some of the earlier signs of collisions.

However, Hyperion's crater differs from the impacts on Phoebe and Iapetus. They tend to be deeper and show no signs of ejecta, giving the moon a sponge-like appearance. The moon's low density and porous surface may explain itsunique appearance.

The interiors of the craters are darker than the rest of the moon's reddish coloration. The low temperature, averaging minus 180 degrees C (minus 300 degrees F), could allow volatile materials to change state while skipping its liquid state, leaving darker materials on the crater floors. Some scientists think that the material might absorb more sunlight, excavating the craters as the material sublimated, while others think the distance from the sun weakens the effect too much.

Quick facts

- Average orbital distance: 932,637 miles (1,500,934 km)

- Closest approach: 911,000 miles (1,466,112 km)

- Farthest approach: 954,275 miles (1,535,756 km)

- Orbit eccentricity: 0.232

- Mass: 5.5855 x 1018 kilograms

- Density: 0.544 grams per cubic centimeter

- Escape velocity: 166 mph (268 kph)

Additional reporting by contributor Elizabeth Howell.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd