Eco-Friendly Galaxy Wastes Nothing to Build Stars

Scientists have found what may be the most environmentally friendly galaxy ever seen, a galactic star factory that operates with a nearly 100-percent efficiency rate. It is located about 6 billion light-years from Earth.

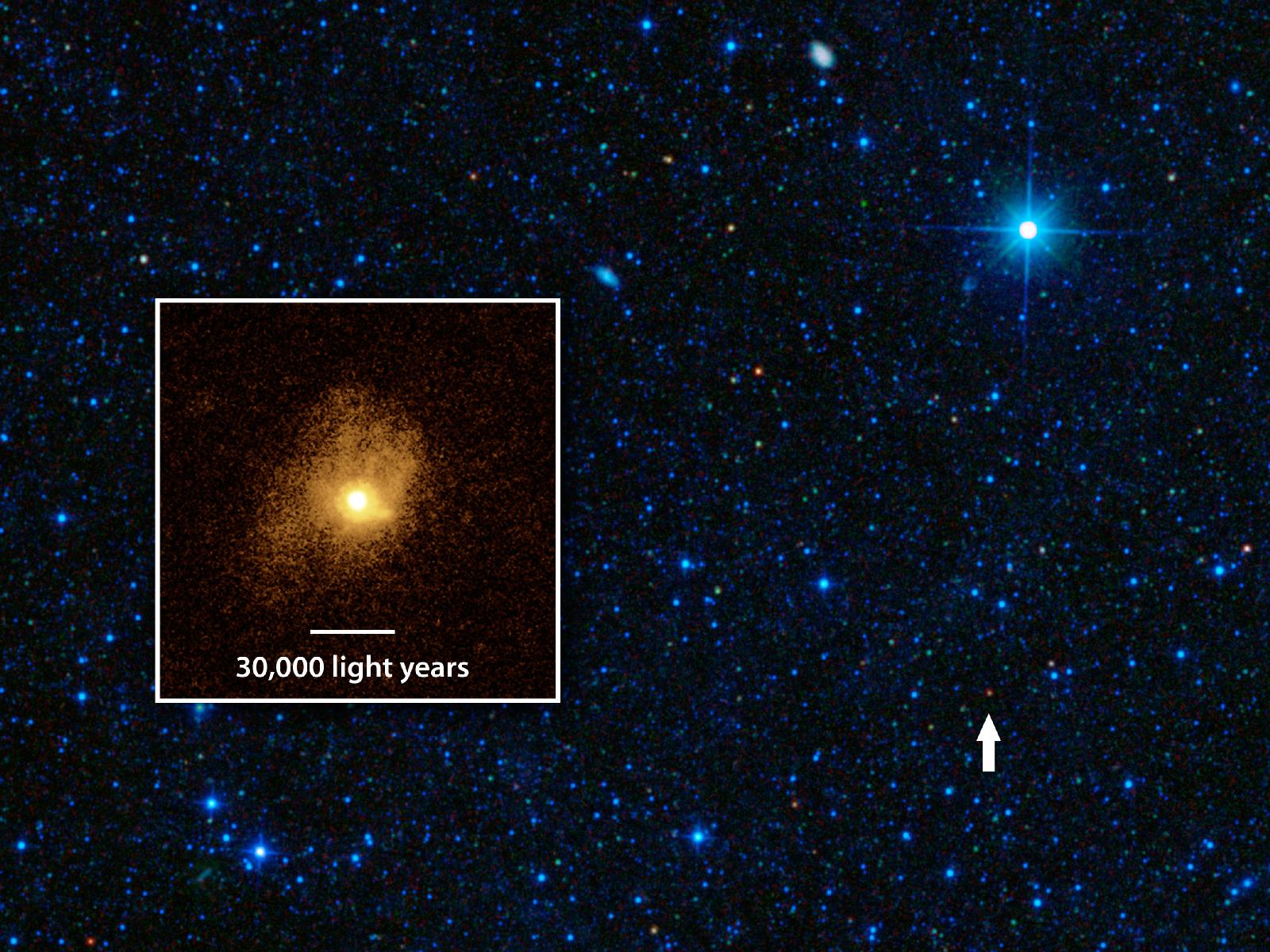

NASA unveiled the galaxy discovery today (April 23), one day after Earth Day, and dubbed the distant galaxy, called SDSSJ1506+54, the "greenest" ever seen. It was spotted by NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) telescope.

Most galaxies use just a small fraction of their available fuel to make stars, but SDSSJ1506+54 is quickly consuming all its gas for star formation. And while stars tend to form in discrete knots of activity in the spiral arms of most galaxies, in this case, gas has collected in the galaxy's center, where a furious riot of star formation is taking place.

"We are seeing a rare phase of evolution that is the most extreme — and most efficient — yet observed," astronomer Jim Geach of McGill University, who led the study, said in a statement.

The galaxy SDSSJ1506+54 is converting gas into baby stars at the maximum rate thought possible, Geach said. [Stunning Galaxy Photos by NASA's WISE Telescope]

Stellar nurseries

New stars form when gas condenses under the weight of gravity, squeezing atoms to the point that nuclear fusion ignites. But when stars form, their powerful radiation blows gas outward, counteracting the condensing action of gravity, making it harder for the gas around them to form new stars. This effect limits the maximum possible rate of star formation, even in galaxy SDSSJ1506+54.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We see some gas outflowing from this galaxy at millions of miles per hour, and this gas may have been blown away by the powerful radiation from the newly formed stars," said study co-author Ryan Hickox, an astrophysicist at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.

Despite its oddness, SDSSJ1506+54 is probably not a weird type of galaxy, but rather a normal galaxy caught in a short-lived phase of evolution, the scientists say. Within a few tens of millions of years, the galaxy will likely have used up most of its gas and will become a typical elliptical galaxy.

Bright stars

The researchers first noticed the galaxy in all-sky survey data collected by NASA's WISE space telescope, which ended its mission in 2011. In infrared light, the galaxy glows with the brightness of 1 trillion suns, researchers said.

Observations of the galaxy from the Hubble Space Telescope in visible light then revealed the extreme compactness of the galaxy, where most of the light was coming from a region just a few hundred light-years across.

"While this galaxy is forming stars at a rate hundreds of times faster than our Milky Way galaxy, the sharp vision of Hubble revealed that the majority of the galaxy's starlight is being emitted by a region with a diameter just a few percent that of the Milky Way," said Geach.

To measure how much gas was contained in the galaxy, the astronomers used the IRAM Plateau de Bure interferometer in the French Alps. It detected millimeter-wave light from the galaxy, which is an indicator of hydrogen gas, the main fuel for stars. These measurements, combined with the estimated rate of star formation in the galaxy derived from WISE data revealed the excellent efficiency of galaxy SDSSJ1506+54 in turning gas into stars.

The findings are detailed in a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.