Unplanned Spacewalk a 'Precedent-Setting' Move for Space Station Crew

HOUSTON — Astronaut Tom Marshburn was planning to spend Saturday (May 11) packing for home. After five months in space, his ride back to Earth is set to leave the International Space Station in just a couple of days.

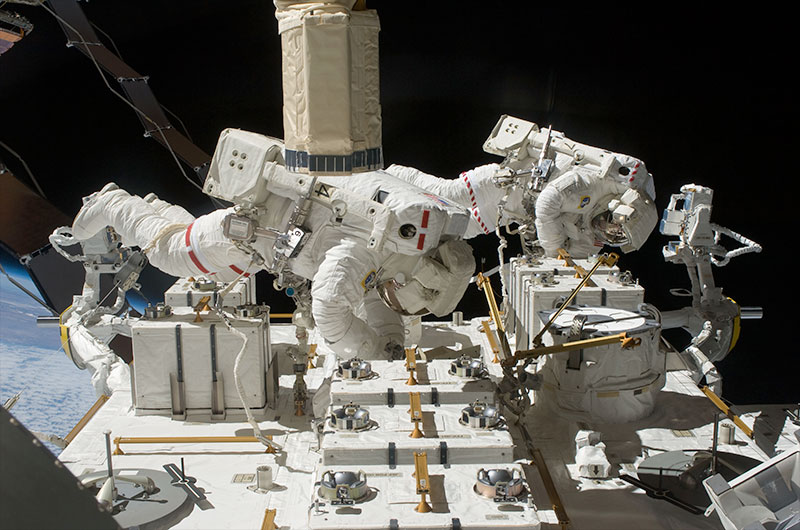

But instead of getting ready for his return, Marshburn and his fellow flight engineer Chris Cassidy are making a last-minute spacewalk in hopes of finding and fixing a coolant leak in the orbiting outpost's main power system.

The contingency spacewalk is the latest in a long but still relatively-rare record of unplanned extravehicular activities (or EVAs) carried out by NASA astronauts. Under normal circumstances, the U.S. space agency prepares its crew members and ground teams to conduct spacewalks with the benefit of weeks of planning and months of training. [Watch the spacewalk live]

Saturday's spacewalk was devised and scheduled in less than two days.

"From purely a station perspective, during an increment, I would say this is precedent-setting," Norm Knight, NASA's chief flight director, said Friday in a press briefing.

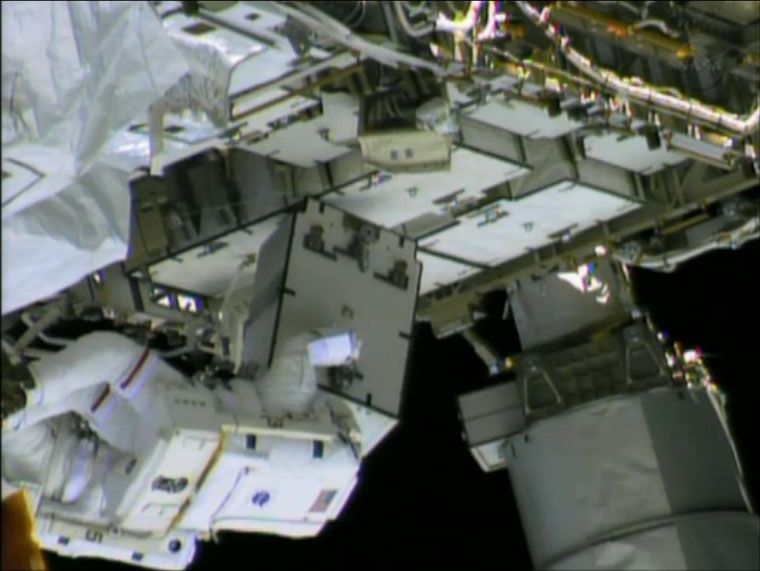

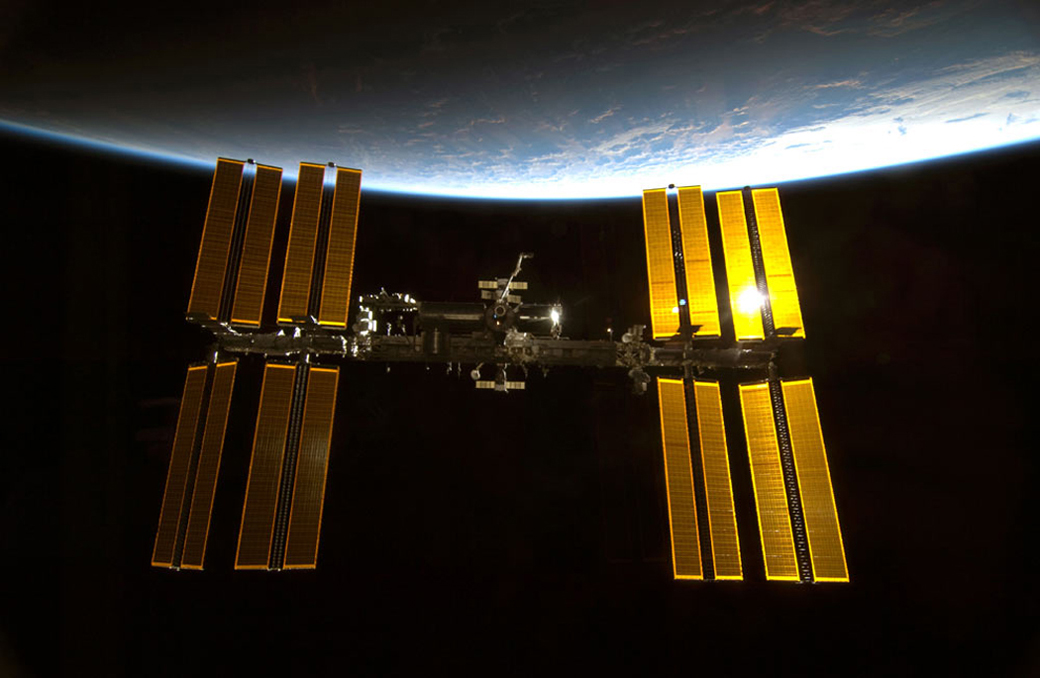

On Thursday (May 9), Marshburn and his space station crewmates reported seeing small white flakes floating away from the far left-side of the space station's truss structure. Imagery captured by the astronauts and data analyzed by Mission Control revealed ammonia used to cool the station's power channels was leaking at an alarmingly-increasing rate.

The crew was never in any danger — at worst, one of the station's eight power channels would be disabled and the systems it fed electricity to would be rerouted, maintaining full operations. But two things conspired to make a quick spacewalk prudent: the dissipating trail of the white flakes and the spacewalks Marshburn and Cassidy did together in 2009. [See photos of the spacewalkers hunting the ammonia leak]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The fact that these two crew members had been out before and done an EVA together in this area is one of the many factors that allowed us to do the EVA before they departed," Michael Suffredini, NASA's International Space Station program manager, told collectSPACE.com. "The systems on the ISS are fine with seven of eight channels, so we really don't need to rush for that reason."

"One of the unique opportunities here is that the leak is big enough and conditions are ripe, at least in this phase of the leak, that if we can get in there and actually see the origin of the leak that is still emitting ammonia 'snow,' then we have a chance of figuring out the source of the leak and what we are going to do about it," Suffredini added. "Often times, because the leaks are so small, if it is not snowing, we just won't notice it with eyeballs staring at the very, very small holes or cracks."

During the six-hour spacewalk — in addition to trying to identify what caused the leak, such as the impact from a micrometeoroid — Marshburn and Cassidy are slated to replace the ammonia pump controller box suspected to be source of the problem.

Saturday's spacewalk, which is the 168th in support of the assembly and maintenance of the station, won't interfere with Marshburn going home as planned. Regardless of the outcome of the EVA, he, Expedition 35 commander Chris Hadfield and flight engineer Roman Romanenko will leave Cassidy and cosmonauts Alexander Misurkin and Pavel Vinogradov on the outpost and return to Earth on board a Russian Soyuz capsule on Monday evening (May 13).

Marshburn's and Cassidy's spacewalk is the not first time astronauts have been called on to quickly suit up and go out. It is not even the first time that an unexpected EVA was made to diagnose an ammonia leak — even from the same area on the space station.

On Nov. 1, 2012, Expedition 33 astronauts Suni Williams and Aki Hoshide conducted a 6 hour, 38 minute unplanned spacewalk in an effort to stop a growing coolant leak from the same truss section where Saturday's EVA is headed. At the time, it was believed that isolating a radiator would stop the leak.

Ammonia coolant was also behind a series of emergency spacewalks in August 2010. At that time, Expedition 24 astronauts Doug Wheelock and Tracy Caldwell Dyson did three EVAs to replace a pump after its sudden failure cut power to the space station.

The history of NASA's unscheduled spacewalks however, extends well beyond leaky coolant loops and back almost three decades.

While the spacewalks to save Skylab, the first U.S. space station, from nearly-crippling launch damage 40 years ago this month required some quickly-devised pre-launch planning and unscheduled in-space tasks, NASA's first unexpected spacewalk unfolded 12 years later in April 1985.

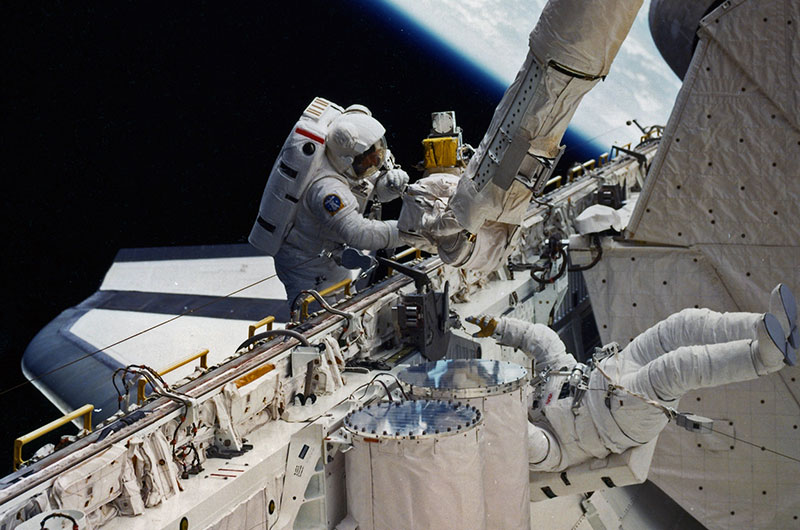

STS-51D crew members David Griggs and Jeff Hoffman didn't know they would be going outside the space shuttle Discovery when they launched on a mission to deploy two communication satellites. But when the second of the two satellites' motors failed to kick in, the astronauts donned spacesuits to attach "flyswatter" devices to the end of the orbiter's Canadarm robotic arm.

The homemade, or rather space-made, arm extensions did work at engaging the start lever but the satellite still failed to deploy.

In the 28 years since, astronauts have made unscheduled EVAs to deploy an orbiting observatory's stuck antenna, capture a satellite with only their hands, pluck a protruding strip of fabric ("gap-filler") from the belly of the shuttle and stitch close a tear in a station solar array using makeshift "cuff-links."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2013 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.