Skylab Legacy: Space Station Astronauts Reflect on 40 Years of Life Off Earth

Before the International Space Station existed, before U.S. astronauts shared space on Russia's space station Mir, America's first home in Earth orbit was Skylab.

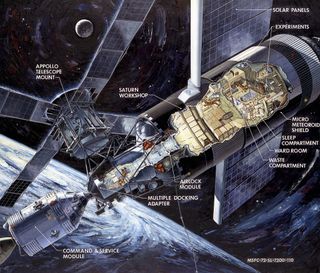

The converted upper stage of a massive Saturn V moon rocket, Skylab was launched 40 years ago today (May 14). The orbital workshop gave NASA its first experience at establishing a long-duration human presence in space, laying the foundation for American astronauts to take up continuous residency almost three decades later on board the International Space Station (ISS).

On Monday (May 13), NASA commemorated four decades of "life off Earth" and the 40th anniversary of Skylab's launch during a roundtable discussion held at its headquarters in Washington, D.C. The event featured Skylab and ISS astronauts, as well as agency managers who are helping to plan the United States' future outposts in space. [Skylab: The First U.S. Space Station (Photos)]

"When these guys went to the final frontier to stay for a long time, they did it as the first ones, the ones who were entering the unknown and to see what it was going to be like and set the stage for us," said astronaut Kevin Ford, who returned from space in March after commanding the International Space Station's Expedition 34. "It is a pleasure for me to be here on the 40th anniversary."

America's first space station

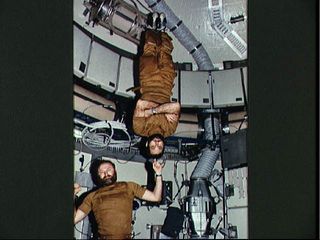

Three crews of three astronauts each launched to the Skylab space station between May and November 1973. Each mission set a record for the amount of time that crewmembers spent in space — Skylab 1 for 28 days, Skylab 2 for 59 days and Skylab 3 for 84 days.

"It verified the fact that people could live, work [and] do productive things for long duration, and also took the first steps toward doing the science that we wanted to have aboard," said Owen Garriott, who served as the science pilot for Skylab's second crew.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That astronauts were even able to spend one day aboard Skylab was a testament to the value of having humans in space.

Excessive vibrations during the station's Saturn V liftoff resulted in a critical meteoroid shield being ripped off in flight, which in turn took out one of the orbital workshop's two power-providing solar arrays. Flight controllers moved Skylab's secondary solar panels to face the sun to provide as much electricity as possible, but because of the loss of the debris shield this caused the station's interior to heat up to over 125 degrees Fahrenheit (52 degrees Celsius).

The effort to "save Skylab" fell to its first crew, who had to quickly prepare for a series of unexpected spacewalks in the short time they had between the station's launch and their own. Despite the very tight schedule, the astronauts successfully deployed a parasol (later augmented by a solar shield) to lower the temperature inside the station and freed a snagged second solar array.

Once the workshop was a stable living platform, the three Skylab crews logged about 2,000 hours in total performing scientific and medical experiments. They also took more than 46,000 photos of the Earth and 127,000 photos of the sun, capturing eight solar flares on film.

The astronauts also devised methods for maximizing their productivity, a lesson with far-reaching applications.

"We dealt with problems having to do with scheduling and productivity," said Gerald "Jerry" Carr, who commanded the final Skylab crew. "We came to some solutions that worked very well. It took a while to get there ... but those solutions that we came across were used on subsequent missions to some degree."

"We tried to make sure that got into the planning for the operations aboard the International Space Station and on the [space] shuttle," Carr added.

"I think we're still working that issue," replied Ford. "We've gotten a much better feeling, I think, now that we are up there to do work that the ground can't necessarily figure out how long it is going to take you to do everything."

The end of Skylab

Upon the end of its crewed missions, Skylab was moved into a stable attitude where it was expected to remain for eight to 10 years. It was hoped that one of the early space shuttle missions could be used to re-boost Skylab's orbit to save the station for future use.

In late 1977, however, four years before the shuttle would first fly, it was discovered that greater-than-predicted solar activity had heated the outer layers of Earth's atmosphere, increasing the drag on Skylab. On July 11, 1979, Skylab re-entered the atmosphere and broke apart over the Indian Ocean. Much of the station burned up or dropped into sea, but its debris field stretched over Australia, where many pieces were later found. [See photos of Skylab's remains in Australia]

Despite its relatively short life span, the use of Skylab's unique environment and vantage point represented a major step in the United States' spaceflight efforts, serving as a bridge between the Apollo missions to the moon and the long-duration expeditions on board the International Space Station, the roundtable said.

"The [International] Space Station was built around what we learned on Skylab," Ford said. "What they put up there for us, the way the modules were sized and the way they were constructed in space... that all came out of what we learned from Skylab."

"We may have done it first, but these guys are doing it better," added Carr, referencing Ford and the current ISS crews. "People need to continue to do it better and better because we learn more and more as we do this. We just took the first step, and the rest of the steps are having had been taken and are being taken right now."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2013 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, an online publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018. He previously developed online content for the National Space Society and Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, helped establish the space tourism company Space Adventures and currently serves on the History Committee of the American Astronautical Society, the advisory committee for The Mars Generation and leadership board of For All Moonkind. In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History.