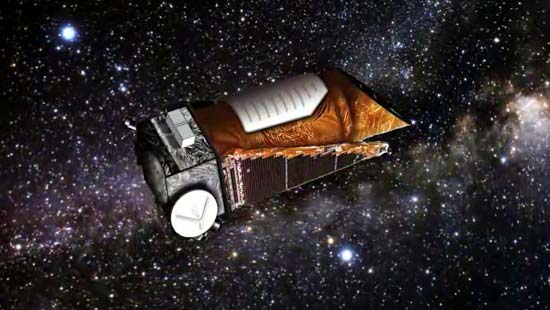

Whether or not NASA's Kepler spacecraft can bounce back from the malfunction that has stalled its search for alien planets, the mission's place in history is assured, scientists say.

Kepler has spotted more than 2,700 potential exoplanets to date, with many more waiting to be plucked from the mission's huge dataset. Its discoveries have opened the eyes of scientists and the public alike, revealing that the Milky Way galaxy abounds with an incredible diversity of alien worlds.

"Kepler has opened up the next set of questions in exoplanets," Paul Hertz, astrophysics director at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., told reporters Wednesday (May 15). [7 Greatest Kepler Planet Discoveries (So Far)]

"Before we flew Kepler, we didn't know that Earth-sized planets in habitable zones were common throughout our galaxy," Hertz added. "We didn't know that virtually every star in the sky had planets around them. Now we know that."

An uncertain future

The Kepler spacecraft launched in March 2009, kicking off a 3.5-year prime mission to determine how common Earth-like planets are throughout the galaxy.

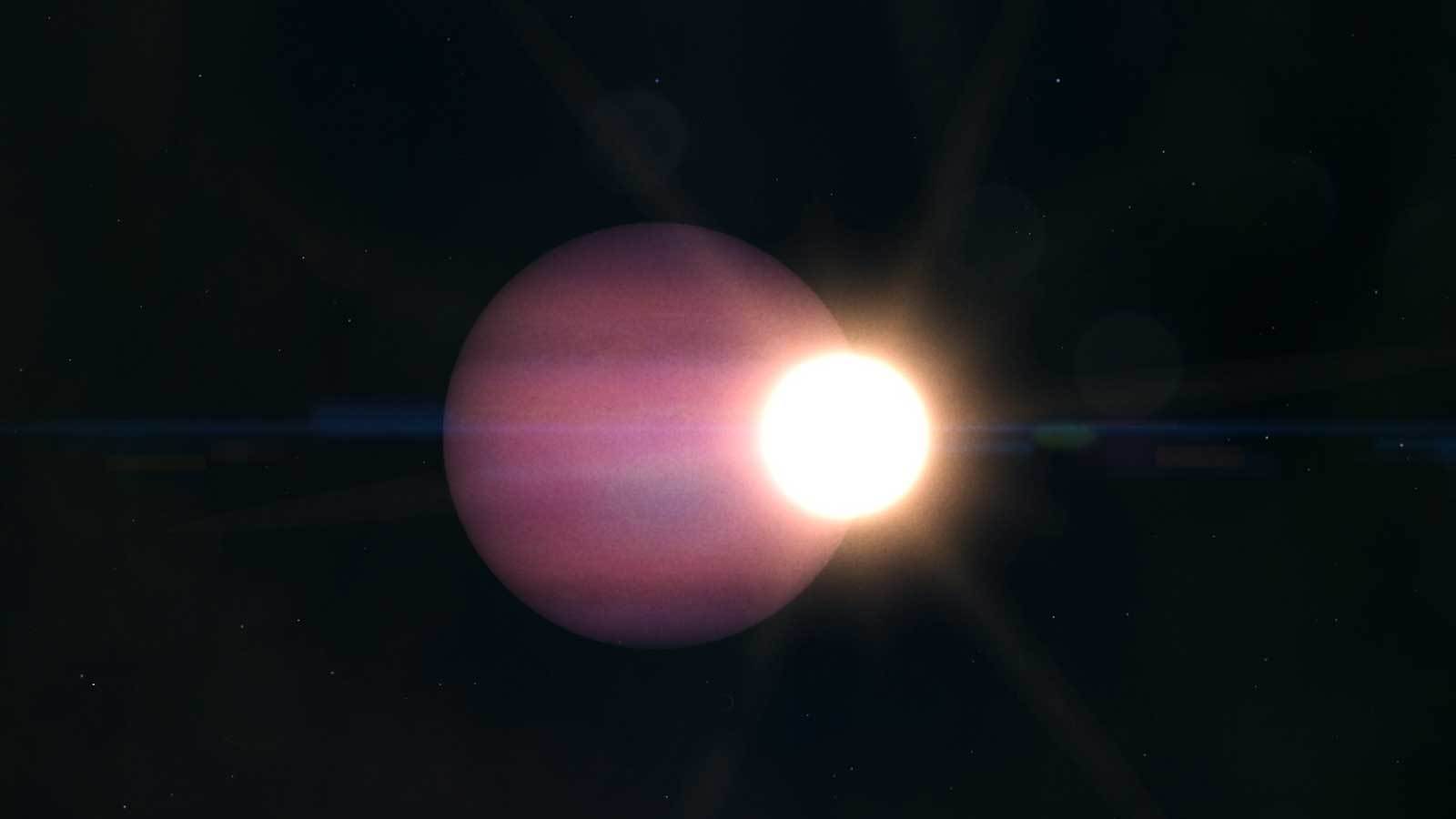

The observatory spots alien worlds by detecting the tiny brightness dips caused when they pass in front of their parent stars from the instrument's perspective. To stay locked onto its 150,000-plus target stars, Kepler needs three functioning reaction wheels, gyroscope-like devices that allow the spacecraft to maintain its position in space.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kepler has four such wheels. But one, known as No. 2, failed in July 2012. And No. 4 has now failed as well, NASA officials announced Wednesday.

Mission engineers will try to bring the two failed wheels back into service over the coming weeks. If they cannot recover at least one wheel, Kepler's planet-hunting days are almost certainly over, though the observatory may get a new mission that doesn't require incredibly precise pointing.

Mapping out a new mission would likely take months, Hertz said.

"It's a technical study that the project needs to do to identify what the options are," he said. "And then we would have to do a scientific study to determine what the benefits of those options might be."

Revolutionizing exoplanet science

While just 132 of Kepler's 2,700 exoplanet candidates have been confirmed to date, mission scientists expect that more than 90 percent will turn out to be the real deal. And the team has had time to go through just half of the spacecraft's dataset thus far, team members said.

"We have excellent data for an additional two years," said Kepler principal investigator Bill Borucki, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif. "So I think the most interesting, exciting discoveries are coming in the next two years."

One such find might be the first true "alien Earth," a potentially life-supporting planet the size of our own. Kepler has already spotted several possibly habitable worlds, including the recently announced Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f, but all of them are slightly larger than Earth.

Future discoveries will be icing on the cake, experts say. Kepler has already revolutionized exoplanet science, giving researchers an unprecedented systematic look at worlds beyond our solar system.

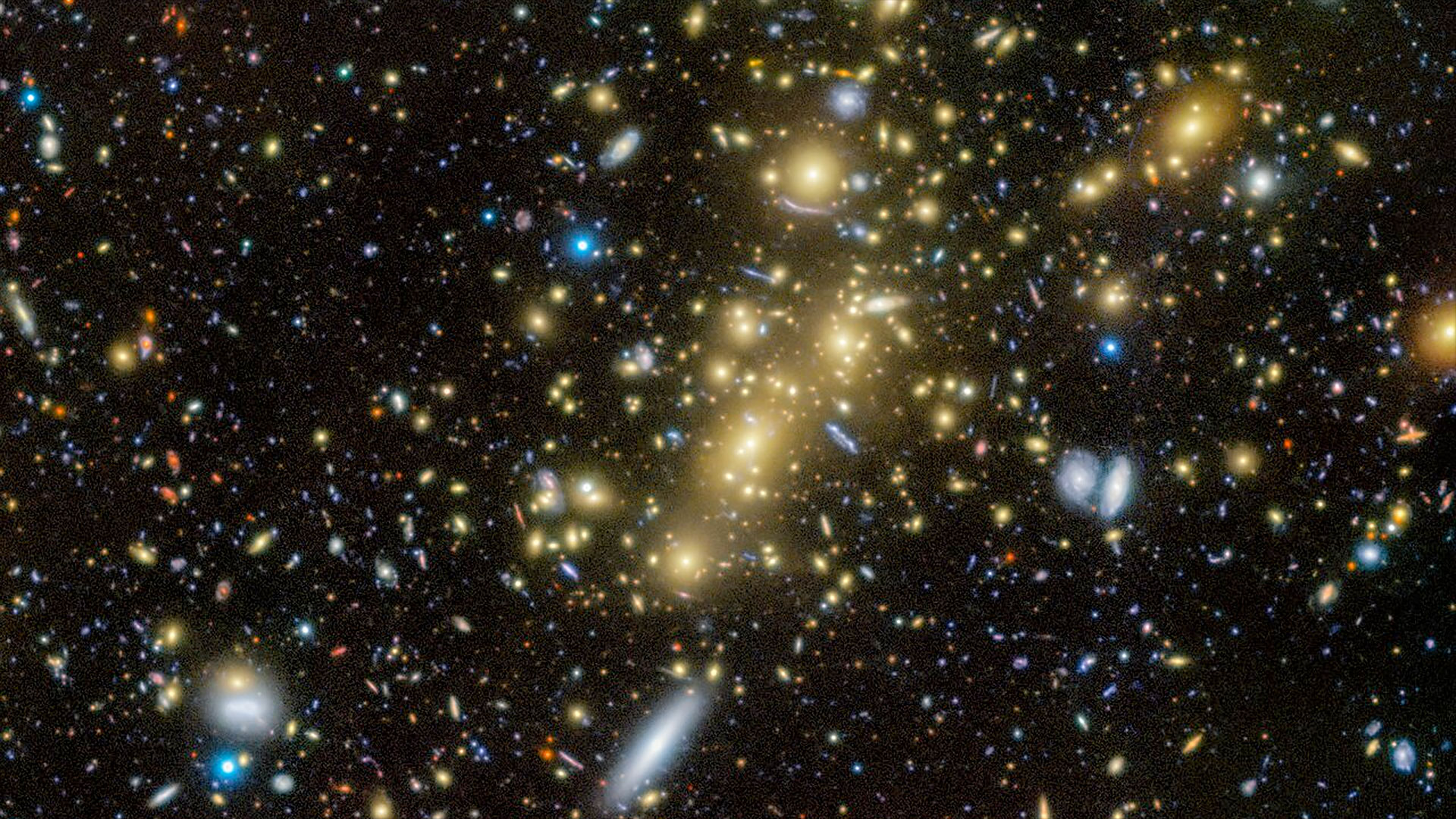

"The science returns of the Kepler mission have been staggering and have changed our view of the universe, in that we now think there are planets just about everywhere," Scott Hubbard of Stanford University said in a statement. (Hubbard, a former NASA "Mars czar," served as director of NASA Ames during much of Kepler's development.)

For example, astronomers recently used Kepler data to estimate that 6 percent of the galaxy's 75 billion red dwarfs — stars smaller and dimmer than the sun — likely host habitable, roughly Earth-size planets. That works out to a minimum of 4.5 billion alien Earths, the closest of which may be just 13 light-years away, according to the study.

Kepler observations have further revealed that small, rocky worlds like our own are much more common throughout the Milky Way than gas giants such as Saturn or Jupiter, at least in relatively close-in orbits.

"It really goes back to, at least for me personally, sitting on my rooftop watching the stars, thinking about what's out there," said NASA science chief John Grunsfeld, a former space shuttle astronaut. "And now we know, because of Kepler and the hard work of all the Kepler scientists."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.