Astronomers have determined a minimum stellar size, helping clarify the line between true stars and strange "failed stars" called brown dwarfs.

All stars should be at least 8.7 percent as wide as our own sun, with average brightnesses no less than 0.00125 percent that of Earth's star, researchers said. They further calculated that all stars likely have surface temperatures of at least 3,140 degrees Fahrenheit (1,727 degrees Celsius).

"That is where the smallest star lives," Todd Henry of Georgia State University told reporters Monday (June 3) at the 222nd American Astronomical Society conference in Indianapolis. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

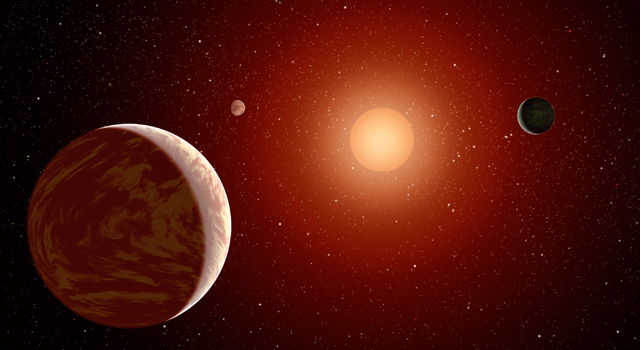

Just above these thresholds lie red dwarfs, which make up about 75 percent of the Milky Way galaxy's stars, he added. Just below are brown dwarfs, odd objects larger than planets but too small to ignite the nuclear fusion reactions that power stars.

Henry leads a project called the Research Consortium on Nearby Stars (RECONS), which was formed in 1994. Since 1999, RECONS has been using the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile to hunt for and characterize nearby red and brown dwarfs.

In the new study, Henry and his colleagues mapped out sizes and various other characteristics for hundreds of stellar and substellar objects using CTIO observations and those made by several other instruments: Chile's Southern Astrophysical Research telescope, NASA's WISE space telescope and the Two Micron All-Sky Survey (which used CTIO and a telescope in Arizona).

"You put it all together, and you find out that there's this dip" at 8.7 percent of the sun's radius, Henry said. "And so that is what we're calling the smallest star."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stars can thus be smaller than some gas giant planets, including Jupiter. But size in this case refers to volume, not mass; stars are much more massive (and thus much denser) than any planet, allowing nuclear fusion reactions to occur in their cores.

Studying nearby red dwarfs is more than just an academic exercise, Henry stressed, saying that these stars present perhaps the best opportunity for discovering life beyond our own solar system.

"These are the stars we're going to search for planets going around them, and eventually for life on those planets. And they are the nearest ones to us," Henry said. "I happen to believe that red dwarfs would be a great place to live, because they last forever."

Other studies have highlighted the intriguing life-supporting potential of red dwarfs. Earlier this year, for example, a separate research team concluded that 6 percent of the Milky Way's 75 billion or so red dwarfs probably host habitable, roughly Earth-size planets.

That works out to at least 4.5 billion such "alien Earths," the closest of which might be found a mere dozen light-years away, researchers said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.