Farmers Discover Rare Meteorite in Minnesota Corn Field

For 40 years, University of Minnesota professor Calvin Alexander has been contacted by people who think they've found meteorites. They call, write, and come in to the lab of the curator of meteorites with rocks they think, or hope, are from outer space. Over four decades, Alexander has seen about 5,000 "meteorwrongs" that turn out to be regular Earth rocks. Until now.

In April, Alexander was contacted by farmers Bruce and Nelva Lilienthal, who sent the professor photos of a peculiar stone they'd found a couple years ago while clearing their corn field in Arlington, Minn.

The rock, which is about 16 inches by 12 inches (40.6 centimeters by 30.5 cm) across, and about 2 inches (5 cm) thick, weighs a surprising 33 pounds (15 kg) — about three times more than a regular Earth rock of that size. Its weight, as well as its unusual flattened shape and rusty surface, immediately suggested it was special. "I said, 'That certainly looks like a meteorite, but I need to see it up close to tell for sure,'" Alexander recalled. [Gallery: See photos of the Lilienthals' meteorite]

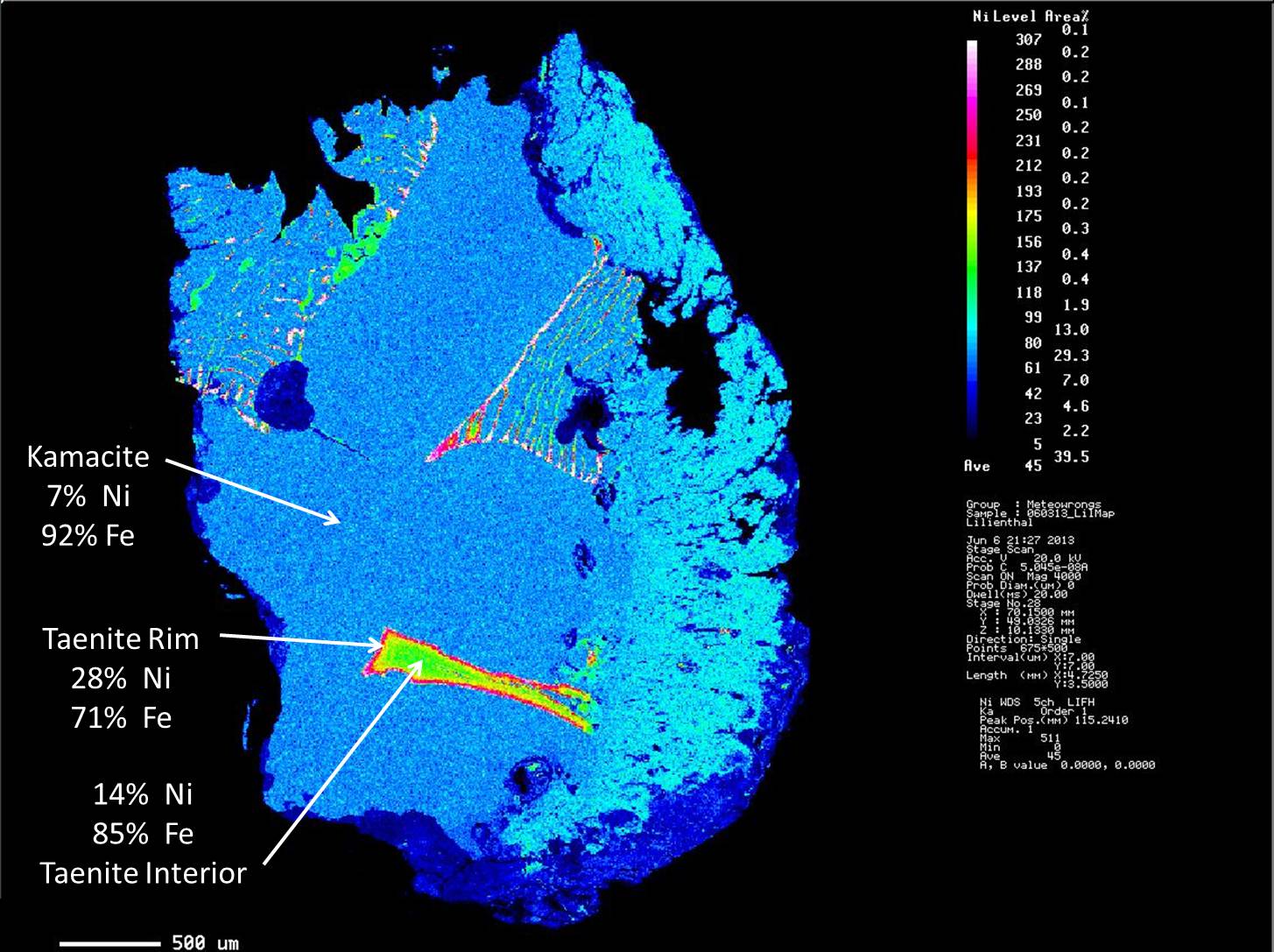

On May 30, the couple brought their find to Alexander's lab and allowed him to chip 0.02 ounces (0.6 grams) off the edge of it for analysis under a scanning electron microscope. The rock was iron, and contained about 8 percent nickel — a telltale giveaway. Iron objects on Earth contain almost no nickel, but iron rocks from space are usually between 5 and 20 percent nickel. The microscope also revealed what's called a Widmanstätten pattern of nickel-iron crystals that's unique to meteorites.

To say that the revelation was welcome news would be a major understatement.

"I am about to retire at the end of next year, and this was the first real meteorite that's been brought in," Alexander told SPACE.com. "Yes, ma'am, I was excited. I am still excited."

Though they haven't spent decades waiting for something like this, the Lilienthals are coming to appreciate their find just as much.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's not something we were expecting to find, but now that we've found out what it is, it's been exciting to learn about it," said Nelva Lilienthal.

Her husband Bruce had come upon the rock two years ago during the annual spring field clearing, when the farmers comb over their land to pick up the many rocks that have been turned up from the frost over the winter.

"You pick up hundreds and hundreds of rocks," Bruce Lilienthal said. "You pick 'em up and you get your fields planted. When we found it, we thought it was kind of different and we put it aside."

The couple noticed the rock's unsettling weight and rare appearance, but didn't think too much of it at the time, and added it to their pile of interesting finds.

"At that point it was time to plant our fields again and we put it off until a rainy day," Nelva said.

Recently, they revisited the issue, and their son, who works for the University of Minnesota, made some inquiries at the school and was referred to Alexander.

Since the discovery of the rock's true nature, the object has taken on more importance.

"It's probably not the prettiest rock that we've got in the pile — it looks kind of like a burnt pizza — but I'm really liking it more," Nelva told SPACE.com. "With all this publicity, it's becoming a favorite."

The future for the space rock is unclear right now. Because it fell on the Lilienthals' property, it legally belongs to them. They may decide to hold onto their meteorite as a prized keepsake, or they may not.

"It's a novelty right now," Bruce said. "The university wants to do more tests on it, so we'll let them do more tests and then we'll decide if we want to sell it or keep it."

Alexander would love to be able to study the rock in detail. He's reasonably sure that the object is another piece of a meteorite that was found in a nearby field in Arlington in 1894 — the two rocks have similar shapes and nickel content. But to tell for sure, a larger chunk of the object would have to be cut off and examined.

The meteorite offers some tantalizing scientific possibilities, Alexander said. For one thing, he'd like to compare the weathering and rusting on the surface of this rock to the 1984 meteorite, which was buried for about 100 years less time before being found.

The meteorite also appears to belong to a rare class of non-magnetic meteorites that originated in melt pools on asteroids created by impacts of other rocks. Additionally, its flattened shape is rare, as most meteorites are roughly spherical.

"Both of those factors mean that it's potentially very scientifically interesting," Alexander said.

The Lilienthals, meanwhile, have a newfound interest in the rocks that turn up in their fields. If their meteorite is related to the 1894 find, it stands to reason there could be more fragments of the same meteorite out there.

"It's very possible there's some in there still underground, still in the field," Bruce Lilienthal said. At the very least, it's made their annual rock-picking-up duty a little bit more exciting, he said.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.