Futuristic British Space Plane Engine to Get Flight Test in 2020

Flight tests of an engine for the giant space plane Skylon are expected by 2020.

The British government and European Space Agency (ESA) are providing $100 million in funding, which will be matched by private financing to complete the propulsion system's development and test.

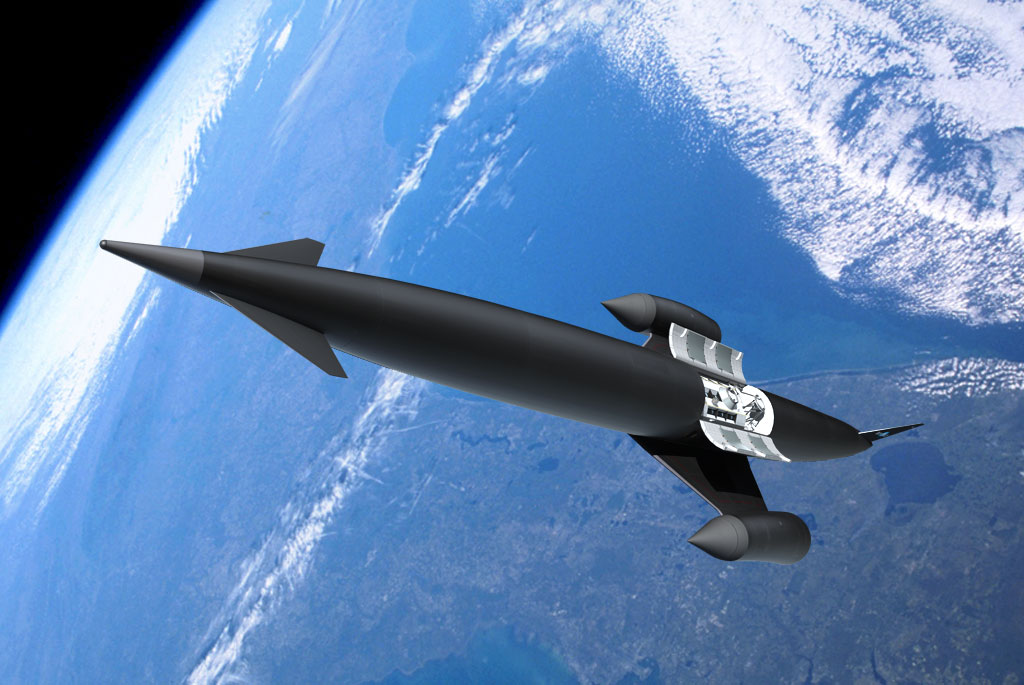

Two Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engines (SABRE) will power the Skylon space plane — a privately funded, single-stage-to-orbit concept vehicle that is 276 feet (84 meters) long. At take-off, the plane will weigh about 303 tons (275,000 kilograms). [Project Skylon: A Giant British Space Plane Concept (Photos)]

The two SABREs are located on the tips of the delta wings attached midway down the Skylon’s dart-like fuselage, powering it to deliver up to 33,000-pounds (15,000 kg) into orbit. That payload could be a satellite or a crew module, officials from its maker, England-based aerospace company Reaction Engines Ltd., have said.

The 2020 flight test will follow the completion of a prototype of the space plane engine by 2017, according to the UK government’s minister for universities and science David Willetts.

Speaking on Tuesday (July 16) at the UK Space Conference 2013 in Glasgow, Scotland, Willetts said: "£60 million ($90 million) has been committed to begin building the SABRE prototype. We expect to see the completion of the prototype SABRE by 2017 and flight tests around 2020."

Reaction Engines’ SABRE development program plans to flight-test the engine using an unmanned aircraft called the Nacelle Test Vehicle. The entire development program will require a consortium of companies, and Reaction Engines has been seeking partners as well as financiers.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Thanks to the government’s support, Reaction Engines will now be able move to the next phase in the development of its engine and heat management technology," Alan Bond, Reaction Engines’ founder, said in a statement.

SABRE burns hydrogen and oxygen for thrust, acting like a jet for Skylon's flight through the thick lower atmosphere, taking in oxygen from the atmosphere to combust it with onboard liquid hydrogen. But when the Skylon space plane reaches an altitude of 16 miles (26 kilometers) and five times the speed of sound (Mach 5), it switches over to its onboard liquid oxygen tank to reach orbit.

For this next phase, the £60 million will be paid in two tranches, £35 million in the UK government’s financial year 2014-2015 and then £25 million for 2015-2016. This funding is expected to create about 1,000 engineering and technology jobs and support a further 2,000 jobs in the wider economy, officials said.

By 2017, the UK government expects that SABRE's design will be done, ground demonstrations of engine technology carried out; a flight test of the SABRE rocket nozzle achieved; and improvements to the heat exchanger technology and manufacturing capability accomplished.

SABRE's heat exchanger, also known as a pre-cooler, is the engine's key technology. Just before the engine switches to rocket mode at Mach 5, the incoming air will have to be cooled from 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius) to minus 238 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 150 degrees C), in one one-hundredth of a second, displacing 400 megawatts of heat energy using technology that weighs less than 2756 pounds (1,250 kg).

The pre-cooler technology was successfully tested in 2012, and the achievement was independently confirmed by ESA, on behalf of the UK government.

"The pre-cooler test objectives have all been successfully met and ESA is satisfied that the tests demonstrate the technology required for SABRE engine development," ESA officials said in November 2012.

Tested at Reaction Engine's B9 facility with a Viper jet engine, a flight-weight pre-cooler ran for the full Skylon ascent duration of six to eight minutes, cooling the Viper's exhaust to cryogenic temperatures. [Video: Skylon Space Plane Delivery]

Willetts' announcement of the £60 million repeats the June 27 post on Twitter from his government's treasury secretary, Chancellor George Osborne, which originally gave the figure. Reaction Engines has confirmed exclusively to SPACE.com that it is also receiving a further 8 million euros ($10.5 million) from ESA, which was approved around the start of the year.

Mark Hempsell, Reaction Engines' future programs director, said that the 8 million euros is to pay for improving the heat exchanger and planning how the £60 million will be spent and leveraged to raise additional private financing.

"It's a case of the government money unlocking the private financing." Hempsell told SPACE.com.

He added that the private and government financing will take SABRE to its critical design review, mature various engine technologies and validate them within a test engine. This test engine is not a subscale version of the SABRE; rather, it is designed to validate the individual SABRE technologies and how they will interact with each other.

The 8 million euros is the latest financial support for SABRE. ESA and the UK government provided about 1 million euros ($1.56 million) in 2009 for a £6 million pre-cooler development program, which led to ESA's 2012 validation.

ESA also gave Skylon a boost in May 2011 when its experts at a UK government-backed three-day technical review found that the Skylon design had no "showstoppers." Other Skylon technologies developed by Reaction Engines include an oxygen-cooled combustion chamber and the rocket engine's nozzle and its intake, which have been computer modeled and tested in a wind tunnel.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob Coppinger is a veteran aerospace writer whose work has appeared in Flight International, on the BBC, in The Engineer, Live Science, the Aviation Week Network and other publications. He has covered a wide range of subjects from aviation and aerospace technology to space exploration, information technology and engineering. In September 2021, Rob became the editor of SpaceFlight Magazine, a publication by the British Interplanetary Society. He is based in France. You can follow Rob's latest space project via Twitter.