Pew! Pew! Pew! NASA Moon Probe Carries Space Laser for Big Tech Test

A NASA probe launching toward the moon tonight (Sept. 6) is carrying a high-tech laser experiment designed to improve deep-space communications.

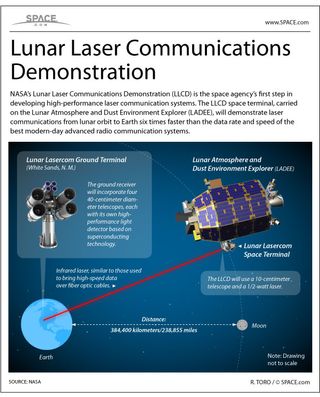

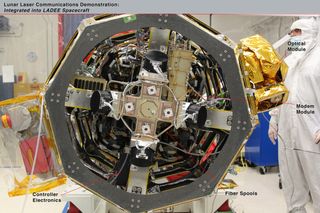

NASA's Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) spacecraft — which is slated to blast off from the agency's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia today at 11:27 p.m. EDT (0327 GMT Sept. 7) — aims primarily to study the moon's wispy atmosphere. But it also totes laser gear to see how well two-way communications can go between a moon-bound spacecraft and the Earth.

The laser experiment may end up helping out a variety of future missions, NASA officials say. [How NASA's Moon Laser Tech Works (Infographic)]

"We can even envision such a laser-based system enabling a robotic mission to an asteroid," Don Cornwell, manager of LADEE's lunar laser communication demonstration at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement. "It could have 3D, high-definition video signals transmitted to Earth providing essentially ‘telepresence’ to a human controller on the ground," Cornwell added.

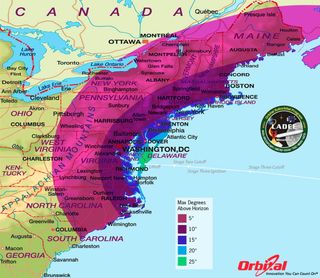

You can watch the LADEE launch live on SPACE.com beginning at 9:30 p.m. EDT (0130 GMT), courtesy of NASA TV. The late-night moon shot will be the first lunar mission ever launched from Virginia and it may be visible, weather permitting, to millions of observers along the U.S. East Coast between Maine and North Carolina. To find out if you live in the viewing area, check out SPACE.com's LADEE rocket launch visibility maps gallery.

More than the Mona Lisa

Since NASA launched its first satellite in 1958, the agency has primarily used radio-frequency communication to keep in touch with its spacecraft. Astronauts used the frequency during the moon landings and the space shuttle program. Voyager, Cassini and other distant robotic spacecraft beamed information back to Earth by radio as well.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The channel, however, only has so much bandwidth. Increases in computer capabilities mean scientists and the public are getting more used to space videos and stills. Also, radio-frequency bandwidth is just about at the limit, NASA said, even as demand soars.

Laser communication, however, offers far more bandwidth, potentially giving the agency better image resolution and the ability to construct 3D videos based on data its spacecraft collect.

LADEE isn't the first laser communicator to leave Earth. In early 2013, NASA scientists used a laser to send a picture of the Mona Lisa — Leonardo da Vinci's most famous painting — to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. It was the first time anyone communicated by laser at such a long distance, 240,000 miles (384,400 kilometers) away.

LADEE's short-duration demonstrator, however, is the first dedicated system to send communications to and from Earth using a laser instead of radio. It can send six times more data using 25 percent less power than an equivalent high-end radio-frequency system, NASA officials said. Plus, laser communications are not as likely to be jammed.

Overcoming cloud interference

The experiment is supposed to send hundreds of millions of bits of data per second from the moon to the Earth — the rough equivalent of 100 high-definition channels transmitted at the same time. The laser demonstrator also is designed to receive tens of millions of bits per second from Earth.

A ground terminal at NASA's White Sands Complex in New Mexico will be the primary avenue for receiving and transmitting information. As backup, a location at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California can receive data, and two-way communication is possible with a European Space Agency terminal in Tenerife, in the Canary Islands off the west coast of Africa.

"Having several sites gives us alternatives, which greatly reduces the possibility of interference from clouds," Cornwell said.

Editor's note: Weather permitting, tonight's LADEE launch should be visible from large stretches of the U.S. East Coast. If you take an amazing photo of the LADEE launch or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebookand Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Most Popular