Mysterious Actions of Chinese Satellites Have Experts Guessing

A set of three mysterious satellites has experts guessing about the Chinese space program's intentions. No one really knows what the Chinese are up to, and everything is speculation.

That appears to be the consensus of space experts tracking a set of Chinese spacecraft. Some have speculated that the Chinese are testing possible anti-satellite technology, while others have described the satellites as prosaic probes meant to sharpen the country's overall space skills.

Under debate are the orbital antics of several newcomers to space — the Chinese satellites Shiyan-7, Chuangxin-3 and Shijian-15 — which all launched into orbit together on July 20. Experts are also discussing the actions of China's elder spacecraft Shijian-7, which launched more than eight years ago. [Most Destructive Space Weapons Concepts]

One of the trio of new Chinese satellites, Shiyan-7 (SY-7, Experiment 7), has since made a sudden maneuver. That satellite had already finished a series of orbital alterations that put it close to one of the companion satellites with which it was launched, the Chuangxin-3 (CX-3).

"Suddenly, however, it made a surprise rendezvous with a completely different satellite, Shijian 7 (SJ-7, Practice 7), launched in 2005," noted Marcia Smith, a space policy analyst and founder and editor of SpacePolicyOnline.com.

'Arming' the heavens?

Soon after the July launch, it was known that one of the three satellites carried "a prototype manipulator arm to capture other satellites," a tool that might be "a predecessor of an arm destined to be aboard China's large space station, set for launch in 2020 or soon thereafter," wrote Bob Christy on zarya.info. (SpacePolicyOnline.com also reported the news.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Christy could not confirm at the time which of the three satellites carried that arm.

When the three satellites were hurled skyward in July, the Chinese language press specifically discussed "space debris observation," "mechanical arm operations" and the testing of "space maintenance technologies," said Gregory Kulacki, a senior analyst and China project manager within the U.S.-based Union of Concerned Scientists' Global Security Program.

"This suggests one possible project for the mission is the experimental collection of space debris," Kulacki told SPACE.com.

The recent July 20 launch also resembles the lofting of the Changxin 2 and the Shiyan 3 satellites in November 2008, Kulacki said. Changxin 2 was an Earth observation microsatellite, while Shiyan 3 was an experimental spacecraft designed for space weather experiments, he said.

From benign to malign

The mystery surrounding the recent launches fits the Chinese pattern, said Dean Cheng, a research fellow on Chinese political and security affairs at the Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C.

"Not sure why these are a surprise, other than that the Chinese don't tell us what they're going to do, so anything they do comes without a convenient press briefing," he said. [China's Shenzhou 10 Space Lab Mission in Pictures]

Close proximity maneuvers, like that between the two Chinese satellites, are consistent with a range of possibilities, from the benign (docking, refueling and repairs) to the malign (anti-satellite), Cheng told SPACE.com.

"But it is perhaps useful here to recall that the People's Republic of China remains intent upon establishing space dominance as part of their thinking about 'fighting and winning local wars under informationized conditions,'" Cheng said. And, even as the Chinese call for greater military-to-military contact with the United States, it's true "that they remain opaque, and that they pretty much refuse to engage the U.S. on military space issues."

That is, while China expands its space capabilities, the country is likely just as interested in military capabilities for their expanding array of space systems as it is in peaceful functions, Cheng said.

"Since space systems are largely dual use, it should not be surprising that there would be interest in the ability to maneuver satellites in close proximity … but neither should there be blithe assumptions that this is necessarily for solely peaceful ends," Cheng said.

Choice to make

An anti-satellite (ASAT) capability allows a country to render a satellite non-operational, Smith wrote.

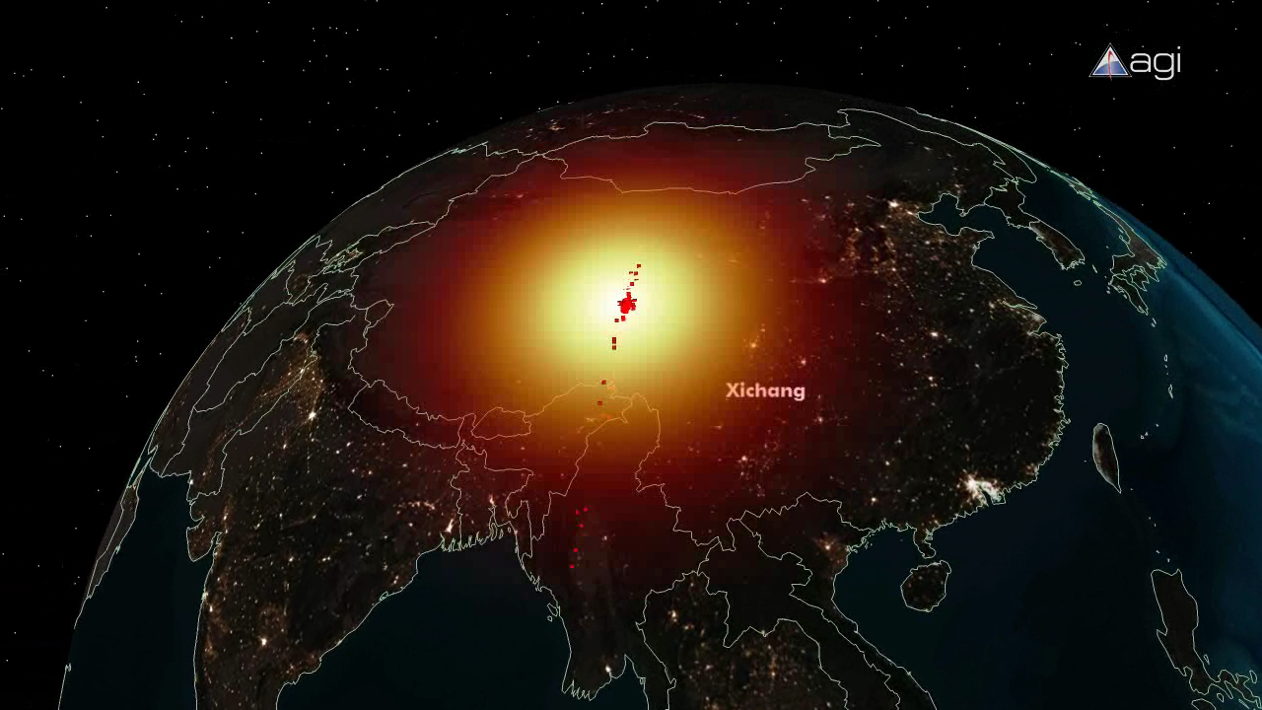

"China conducted an ASAT test in 2007 when it launched a satellite interceptor against one of its own satellites. The test was successful in that it destroyed the satellite, but the resulting cloud of more than 3,000 pieces of space debris in a heavily used part of Earth orbit resulted in international condemnation, and spurred efforts to develop an internationally accepted code of conduct to ensure space sustainability," Smith said onSpacePolicyOnline.com.

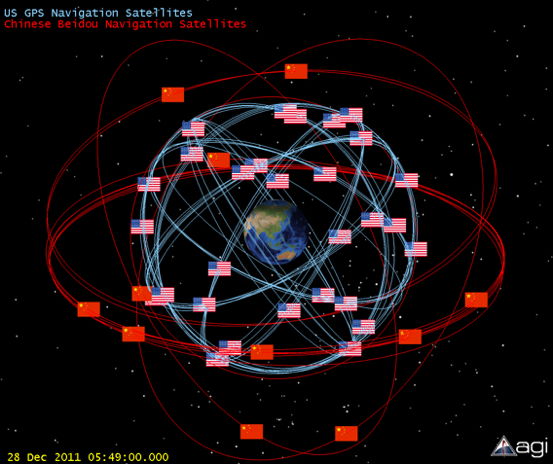

But both China and the United States are experimenting with close-proximity maneuvers in space, said Michael Krepon, co-founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Stimson Center and director of its South Asia and Space Security programs. Both nations have demonstrated ASAT capabilities, Krepon told SPACE.com.

Information derived from actual or purported tests for ballistic missile defense, he said, can also be applied for ASAT purposes.

"Beijing and Washington have a choice to make, the same choice that Moscow and Washington faced during the Cold War," Krepon said.

"Major powers can ramp up a competition to damage satellites, or they can arrive at tacit agreements to dampen this competition," he said. "The United States and the Soviet Union chose wisely. China has yet to choose."

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin's new book "Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration" published by National Geographic. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.