For NASA, it's official: Voyager 1 has entered interstellar space. But given the many false alarms over the years, what makes scientists so confident now?

This time, researchers have used several clues about plasma changes around Voyager 1 to determine that it entered interstellar space around Aug. 25, 2012. NASA announced that Voyager 1 has arrived in interstellar space on Thursday (Sept. 12).

"We looked for the signs predicted by the models that use the best available data, but until now we had no measurements of the plasma from Voyager 1," said Voyager Project Scientist Ed Stone of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, in a statement. [Voyager 1's Trek to Interstellar Space (A Photo Timeline)]

No way to know

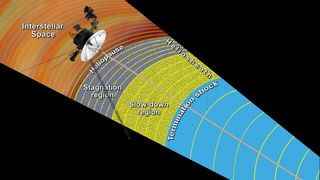

One of the most convenient ways to determine the location of Voyager 1 is to measure the temperature, pressure and density of plasma, or ionized gas, around the spacecraft. Everything inside the solar bubble, or heliosphere, should be exposed to plasma that streams from the sun, whereas interstellar space is filled with denser plasma from the explosion of giant stars millions of years before.

Unfortunately, the 36-year-old spacecraft's plasma detector broke in 1980.

Compounding the problem was that interstellar space was completely uncharted territory. The simple models to predict how Voyager would behave as it left the heliosphere didn't match data coming from the spacecraft.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"No one has been to interstellar space before, and it's like traveling with guidebooks that are incomplete," Stone said.

Signs of transition

The team expected to see a shift in the direction of the magnetic field at the boundary between interstellar space and the heliosphere. They also expected to see a sharp drop in the presence of charged particles from the sun and a rise in cosmic radiation from interstellar space.

In May 2012, scientists detected a drop in charged particles and a jump in cosmic rays. Those changes accelerated around July 28, 2012, but the levels soon returned to normal.

But by Aug. 25, all the particles originating inside the heliosphere dropped dramatically and cosmic ray levels skyrocketed — and the levels stayed that way. At first, this seemed to confirm that Voyager 1 had left the heliosphere, but the magnetic field direction had shifted only 2 degrees, a miniscule amount.

Plasma changes

But in April 2013 scientists remembered that Voyager I had experienced bursts of radio waves in 1983 to 1984 and in 1992 to 1993 when interstellar plasma was bombarded with a huge blast of solar material. They expected to find similar oscillations once Voyager was jolted by interstellar plasma.

On April 9, they noticed those oscillations, which likely occurred a year before due to a solar storm around St. Patrick's Day. The oscillations got bigger, indicating that Voyager was entering the much denser plasma of interstellar space.

Most of the clues indicated that Voyager 1 was indeed surrounded by interstellar space.

But charged particles were still bombarding Voyager preferentially from certain directions; in interstellar space, charged particles were supposed to come from all directions. Despite being bathed in interstellar medium, Voyager was still inside the sun's realm of influence.

"In the end, there was general agreement that Voyager 1 was indeed outside in interstellar space," Stone said. "But that location comes with some disclaimers — we're in a mixed, transitional region of interstellar space. We don't know when we'll reach interstellar space free from the influence of our solar bubble."

But while Voyager 1 is in interstellar space, there's a caveat that comes with its exit from the solar system, NASA officials added.

"Informally, of course, "solar system" typically means the planetary neighborhood around our sun," they explained in a statement. "Because of this ambiguity, the Voyager team has lately favored talking about interstellar space, which is specifically the space between each star's realm of plasma influence."

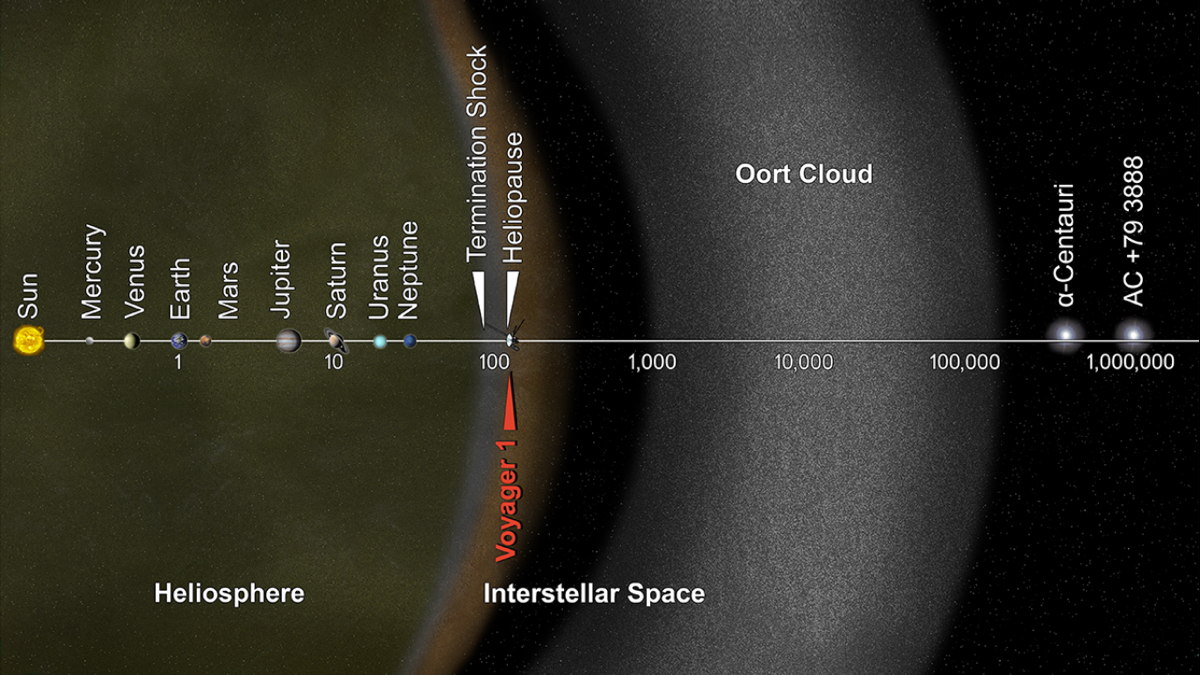

Technically, Earth's most distant spacecraft is still inside the solar system since it has 300 years till it reaches the inner edge of the vast Oort cloud where comets are born. The journey through the Oort cloud could take another 30,000 years, NASA officials said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tia is the assistant managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science, a Space.com sister site. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.