Black Holes May Have 'Hair'

Black holes may not be bald after all.

In a challenge to traditional models of the universe's gravitational monsters, new research suggests black holes could be quite "hairy," with more tangled features than previously believed.

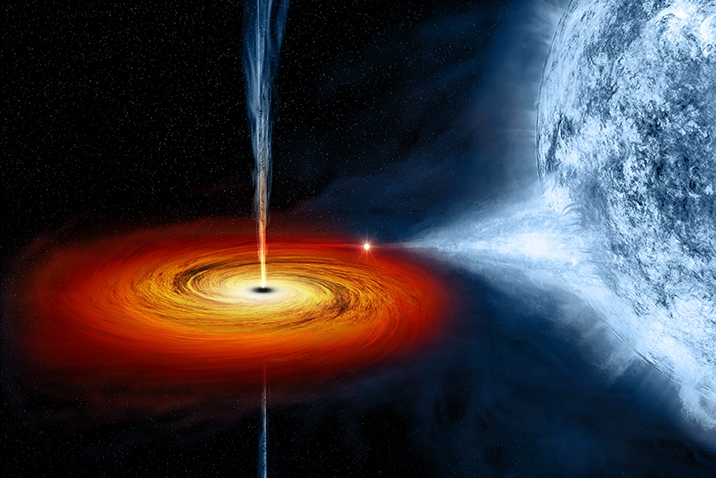

The gravitational attraction of black holes is so strong that even light cannot escape their pull, making these super-dense objects invisible to outside observers and almost indistinguishable from one another.

"The accepted picture is that black holes are very simple objects that can be fully characterized by only 3 quantities: their mass, their angular momentum (how fast they spin) and their electric charge," Thomas Sotiriou, a physicist at the International School for Advanced Studies of Trieste, told SPACE.com in an email.

The electric charge, however, is usually negligibly small, and researchers typically throw it out when describing a black hole.

Astronomer John Wheeler, who coined the term "black hole" nearly 50 years ago, famously said that "black holes have no hair" because of their simplicity. Now "hair" is used as a colloquial term among physicists as a stand-in for any other measure needed to describe a black hole that departs from the traditional three-quantity model.

For their study, Sotiriou and his colleagues looked at black holes in the context of the equations of scalar-tensor theories of gravity.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"These are theories different than Einstein's theory, general relativity," Sotiriou wrote in an email. "They also describe the gravitational field in term of curvature of spacetime and predict the existence of black holes. However, they include also a different kind of field — a scalar field — to participate to the mediation of the gravitational interaction."

The researchers found that black holes develop scalar "hair" when ordinary matter surrounds them.

"This does not happen in the standard picture," Sotiriou said.

It's not clear from the study if these strands of scalar "hair" make black holes look much different from the standard picture, and it's not clear how observable the effect is with current technology, Sotiriou explained.

Not only would the existence of "hair" help researchers understand the structure of black holes themselves, proof of "hairy" black holes could represent a paradigm shift, Sotiriou said, since Einstein's theory does not include a scalar field.

The study was detailed in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.