'Gravity' and Reality: History's Worst Space Disasters

In the space thriller "Gravity," audiences witness the terrifying prospect of an astronaut adrift in space. The film, which set an October-opening record with $55.6 million over the weekend, stars Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as astronauts cut loose after satellite debris cripples their space shuttle.

The gripping depiction of a space disaster in "Gravity" may be fictional, but the potential for death and destruction has long haunted the final frontier, said Allan J. McDonald, a NASA engineer who wrote "Truth, Lies and O-Rings" (University Press of Florida, 2009) about the Challenger disaster.

"It was always extremely risky business," McDonald said. [Fallen Heroes of Space Travel: A Memorial (Gallery)]

Here are the biggest real-life disasters in spacefaring history, as well as a few near-misses:

Soyuz 1 dooms cosmonaut: The first fatal accident in a space mission befell Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov, whose problem-plagued Soyuz 1 capsule crashed onto Russian soil in 1967. In "Starman" (Walker & Co., 2011), a KGB source claims that Komarov and others knew the capsule would fail, but that Soviet leadership ignored their warnings.

Different accounts agree that parachute malfunctions caused the crash. Audiotapes recorded the cosmonaut's last communications with ground control, during which "Starman" claims the cosmonaut "cried in rage" at the engineers he blamed for the faulty spacecraft.

Deaths in space: The Soviet space program also suffered the first, and so-far only, deaths in space in 1971, when cosmonauts Georgi Dobrovolski, Viktor Patsayev, Vladislav Volkov died while returning to Earth from the Salyut 1 space station. Their Soyuz 11 craft performed a textbook-perfect landing in 1971. So recovery teams were appalled to find the three-man crew sitting dead in their couches, with dark-blue splotches on their faces and blood dripping from their ears and noses.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

An investigation showed that a breathing ventilation valve had ruptured, asphyxiating the cosmonauts. The resulting drop in pressure also exposed the crew to the vacuum of space — the only human beings to ever experience such a fate. They died within seconds of the rupture, which occurred at 168 kilometers (104 miles), making them the only human beings to die in space. Since the capsule ran an automatic re-entry program, the craft could land without living pilots.

The Challenger space shuttle disaster: NASA exited the Apollo era without recording a fatality during a spaceflight mission. That success record changed dramatically on Jan. 28, 1986, when the space shuttle Challenger exploded on live television, shortly after liftoff. The launch had attracted more attention than usual because, for the first time, a teacher was headed to orbit. Set to teach lessons from space, Christa McAuliffe had also attracted an audience of millions of school children.

The disaster traumatized the nation, said James Hansen, a space historian at Auburn University who co-authored "Truth, Lies and O-Rings." "That's what makes Challenger unique," he said. "We saw it happen. We saw it happen over and over."

A high-profile investigation discovered that "O-ring" seals failed due to the cold temperatures on launch day, a risk NASA had known about. The accident prompted technical and cultural changes at the agency, and grounded the shuttle program until 1988.

Columbia space shuttle disaster: Seventeen years after the Challenger tragedy, the shuttle program suffered another loss when the space shuttle Columbia broke apart upon re-entry on Feb. 1, 2003 at the end of the STS-107 mission.

Investigations traced the disaster to damage from foam debris the shuttle had shed. The seven-member crew may have survived the initial breakup, but quickly lost consciousness and died as the shuttle continued to break up around them, investigations found. The Columbia shuttle disaster, sadly, repeated some of the mistakes from the Challenger era, McDonald said, with warnings about debris going largely unheeded. The next year, President George W. Bush announced the retirement of the shuttle program. [Columbia Space Shuttle Disaster Explained (Infographic)]

Apollo's 1 fire: Though the Apollo missions never lost an astronaut during a spaceflight, two fatal accidents did occur during related activities. Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Edward White II and Roger Chaffee perished during a supposedly "non-hazardous" grounded test of the command module on Jan. 27, 1967. A fire engulfed the cockpit, asphyxiating all three astronauts, before burning their bodies.

Investigations placed blame on several errors, including the use of pure oxygen in the cabin, flammable Velcro strips and an inward-opening hatch that trapped the crew. Before the test, the three astronauts had shared worries about the cockpit, and posed for a photo praying in front of a model of the vehicle. [Apollo 1 Fire Remembered (Infographic)]

The accident resulted in congressional investigations that could have canceled Apollo, but ultimately prompted design and procedural changes that improved future missions, Hansen said. "If the fire hadn't happened, a lot of people say we wouldn't have successfully reached the moon," Hansen said.

X-15 rocket plane crash:In another Apollo-related mission, astronaut-in-training Michael Adams crashed an X-15 rocket-powered plane in 1967. Adams had passed 50 miles (80.5 km) in altitude, so some consider this a spaceflight fatality.

Apollo 13 — "Houston, we have a problem": The Apollo program owes its success record, in part, to quick-thinking actions that prevented other catastrophes. In 1966, the agency successfully docked the Gemini 8 spacecraft with a target vehicle, but the Gemini craft entered an uncontrolled roll. At one revolution per second, the spin could have caused astronauts Neil Armstrong and David Scott to black out. However, Armstrong corrected the roll by shutting off the malfunctioning main thrusters and taking control using re-entry thrusters.

Made famous in the 1995 film of the same name, Apollo 13 could have left its astronauts stranded in space. An oxygen tank exploded, damaging the Service Module and scuttling the intended moon landing. To get home, the astronauts had to slingshot the craft back to Earth using the moon's gravity. After the explosion, astronaut Jack Swigert radioed mission control to say, "Houston, we've had a problem." The film gives the famous line instead to Jim Lovell, played by star Tom Hanks, altering the phrase to the more immediate, "Houston, we have a problem."

Lightning and wolves: Both NASA and the Soviet/Russian space programs have faced a few interesting, though not catastrophic, threats. In 1969, lightning struck the same spacecraft twice, when bolts shot through the Apollo 12 vessel at 36 and 52 seconds after liftoff. The mission proceeded smoothly, however.

Due to a 46-second delay caused by a cramped cabin, cosmonauts Alexey Leonov and Pavel Belyayev's 1965 Voskhod 2 craft missed its original re-entry site. Instead, the ship crashed into the deeply forested Upper Kama Upland region, where wolves and bears stalked the wilderness. Leonov and Belyayev spent the night huddled in the cold, gripping a pistol in case of attack (none came).

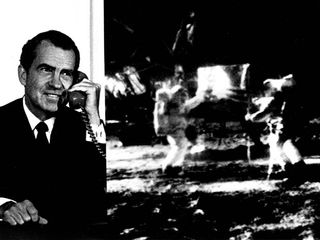

What If? Nixon's Apollo 11 Speech: Perhaps the most fascinating space disaster never actually happened — except in the minds of contingency planners. History records the potential disaster in a speech written for President Richard Nixon during Apollo 11 in case astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong were left stranded on the moon during the first manned lunar landing.

The text announces that, "Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace."

If that had happened, the future of spaceflight, and the public's perception of it, might have been much different, Hansen said. "If we on Earth had to imagine dead bodies on the lunar surface … the specter of that would have haunted us. Who knows, it could have shut the program down."

Follow Michael Dhar @michaeldharor epicdarwin.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Dhar is a manuscript editor at the American Medical Association and a freelance science and medical writer and editor, having written for Live Science, Space.com, Earth.com, The Fix, Scientific American, and others. Michael received a master's degree in Bioinformatics from NYU's Polytechnic School of Engineering, and also has a master's in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University School of New York, and a bachelor's in English with a biology minor from the University of Iowa.