Moon Dust Mystery Solved With Apollo Mission Data

A revisited trove of data from NASA's Apollo missions more than 40 years ago is helping scientists answer a lingering lunar question: How fast does moon dust build up?

The answer: It would take 1,000 years for a layer of moon dust about a millimeter (0.04 inches) thick to accumulate, the researchers found. That rate may seem slow by the standards of Earth but it's 10 times faster than scientists had believed before, and it means moon dust could pose big problems for astronauts and equipment alike.

"You wouldn't see it; it's very thin indeed," Brian O'Brien, a physicist at the University of Western Australia, said in a statement. "But, as the Apollo astronauts learned, you can have a devil of a time overcoming even a small amount of dust." [Lunar Legacy: 45 Apollo Moon Mission Photos]

Kicked-up dust was a nuisance during the Apollo missions. It clung to the astronauts' spacesuits, it smelled like gunpowder and spaceflyer Harrison Schmitt of Apollo 17, the last lunar landing mission, even reported feeling congested and complained of "lunar dust hay fever" after breathing in the particles. Moon dust also wreaked havoc on some experiments. For example, it was blamed for the overheating and early failure of Apollo 11's Passive Seismic Experiment, which was intended to study "moonquakes."

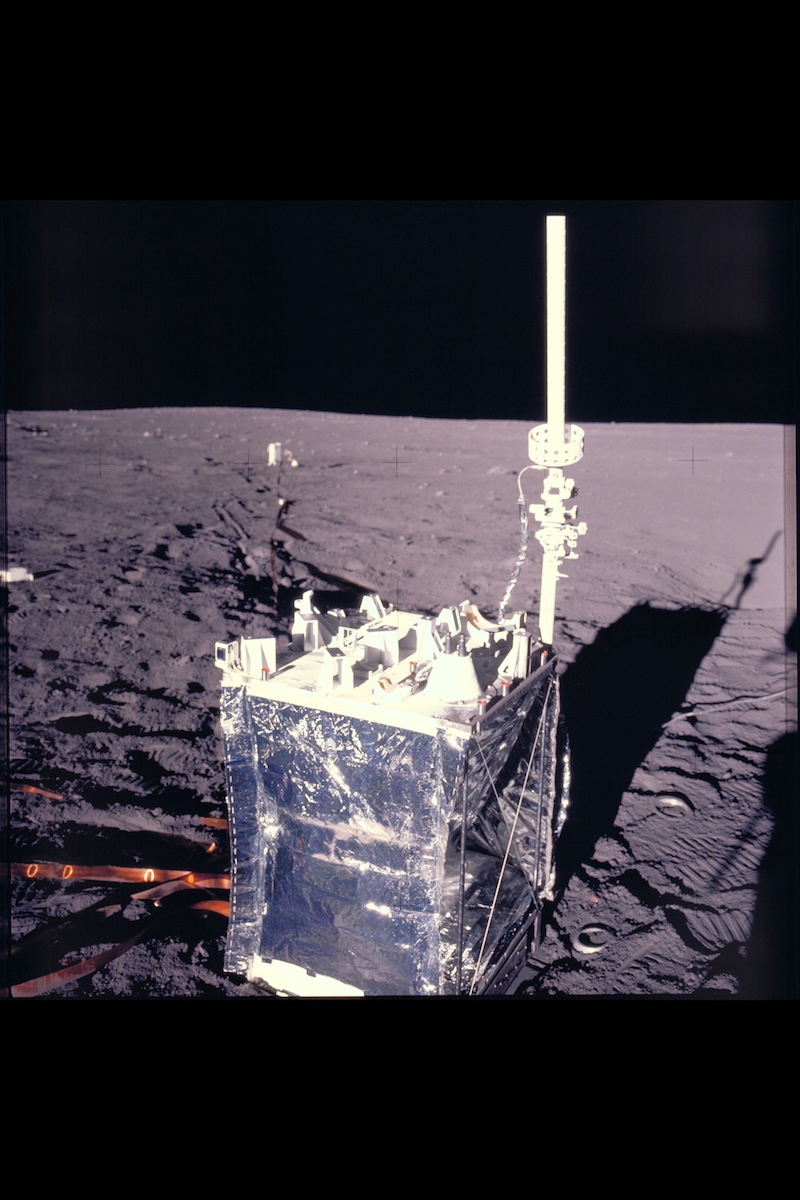

O'Brien actually started his work on moon dust more than 40 years ago while he was a professor at Rice University in Houston and the principal investigator for the Dust Detector Experiment (DDE), which flew during the Apollo 11, 12, 14 and 15 missions.

Each matchbox-sized detector deployed in the experiment was equipped with three solar cells covered with a different amount of shielding against incoming radiation. By tracking the degradation of each of the cells, O'Brien hoped to determine how much damage was caused by dust and how much was caused by radiation.

NASA had lost their tapes of the data that the dust detectors collected and assumed the information from the DDE was lost forever — that is until 2006 when O'Brien told the space agency that he still had a set of backup copies. He revisited the data with his colleague Monique Hollick, a researcher also at the University of Western Australia.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's been a long haul," O'Brien said in a statement. "I invented [the detector] in 1966, long before Monique was even born. At the age of 79, I'm working with a 23-year old working on 46-year-old data and we discovered something exciting — it's delightful."

O'Brien and Hollick's analysis, which was detailed in the journal Space Weather, showed that the dust, rather than radiation, caused the most damage to the protected cells.

The moon has no substantial atmosphere and no wind, which means its dirt should be quite stale. As such, earlier scientific models suggested that any accumulating dust could be traced to meteor impacts and falling cosmic dust.

"But that's not enough to account for what we measured," O'Brien said. The concept of a "dust atmosphere" on the moon could explain where the particles come from, the researchers said.

According to this theory, moon dust particles on the daytime side of the moon can build a positive charge when radiation from the sun kicks electrons out of atoms of dust. But on the side of the moon that's dark, dust particles can gain a negative charge when they are bombarded with electrons from the solar wind. Where the dark and light sides meet, electric forces could levitate this charged dust high off the lunar surface, the researchers said.

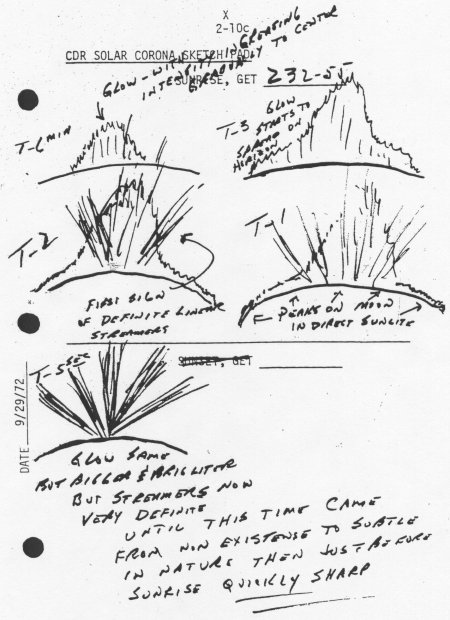

"Something similar was reported by Apollo astronauts orbiting the Moon who looked out and saw dust glowing on the horizon," Hollick explained.

NASA's latest moon orbiter, the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer, or LADEE, which launched in September, could shed light on this levitating dust. At 155 miles (250 kilometers) above the surface of the moon, the spacecraft is looking for dust in the lunar atmosphere.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.