SAN FRANCISCO — The asteroid that exploded over Russia earlier this year died as it had lived — in a welter of chaos and violence.

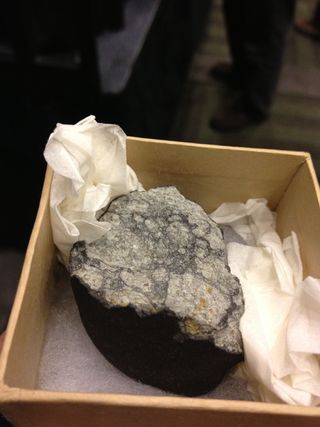

Scientists have pieced together the history of the space rock that slammed into the atmosphere over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk on Feb. 15, creating a shock wave that injured 1,200 people. It's a long, convoluted tale that picks up just after the solar system started coming together 4.56 billion years ago.

Molten droplets that found their way into the Chelyabinsk object formed within the first four million years of solar system history, David Kring of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston said here Monday (Dec. 9) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. [Photos: Russian Meteor Explosion of Feb. 15, 2013]

Over the next 10 million years, these tiny pieces, along with generous helpings of dust, coalesced into an asteroid on the order of 60 miles (100 kilometers) wide. Textures spotted within pieces of the Chelyabinsk asteroid recovered here on Earth reveal that the rock was likely once buried several kilometers beneath the surface of this larger object, which scientists call the LL chondrite parent body, Kring added.

Further, analysis of "shock veins" within Chelyabinsk meteorites indicate that the parent body suffered a major impact about 125 million years after the solar system started forming.

And the hits kept on coming, with the parent body absorbing strike after strike between 4.3 billion and 3.8 billion years ago, Kring said. (Earth and other planets in the inner solar system were also pummeled during this period, which is known as the "late heavy bombardment.")

The LL chondrite parent body apparently then got a break, and was left alone to lick its wounds for a few billion years. But meteorite fragments record evidence of two more large impacts in the last 500 million years, with one of them coming between 30 million and 25 million years ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The next big event for the parent body had consequences for people on Earth as well.

"The meteoroid then encountered a gravitational resonance in the asteroid belt, and that altered its orbit," Kring said. "So at that point, it moved from being a main-belt asteroid to being a near-Earth asteroid."

Work published just a few months ago indicates that the Chelyabinsk asteroid was exposed to space just 1.2 million years ago, suggesting that yet another impact occurred around that time, Kring added.

This collision perhaps finalized the size of the space rock, which is thought to have measured about 65 feet (20 meters) wide when it entered Earth's atmosphere.

"And finally, of course, we have one more collisional event, on Feb. 15, 2013," Kring said.

While the Chelyabinsk asteroid met its end that day, other fragments of the LL chondrite still exist out in the depths of space. One such chunk is the 1,770-foot-long (540 m) asteroid Itokawa, which Japan's Hayabusa spacecraft visited in 2005, gathering samples that were returned to Earth five years later.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.