'Spectacular' Crash On Jupiter Moon Europa May Have Delivered Life's Building Blocks

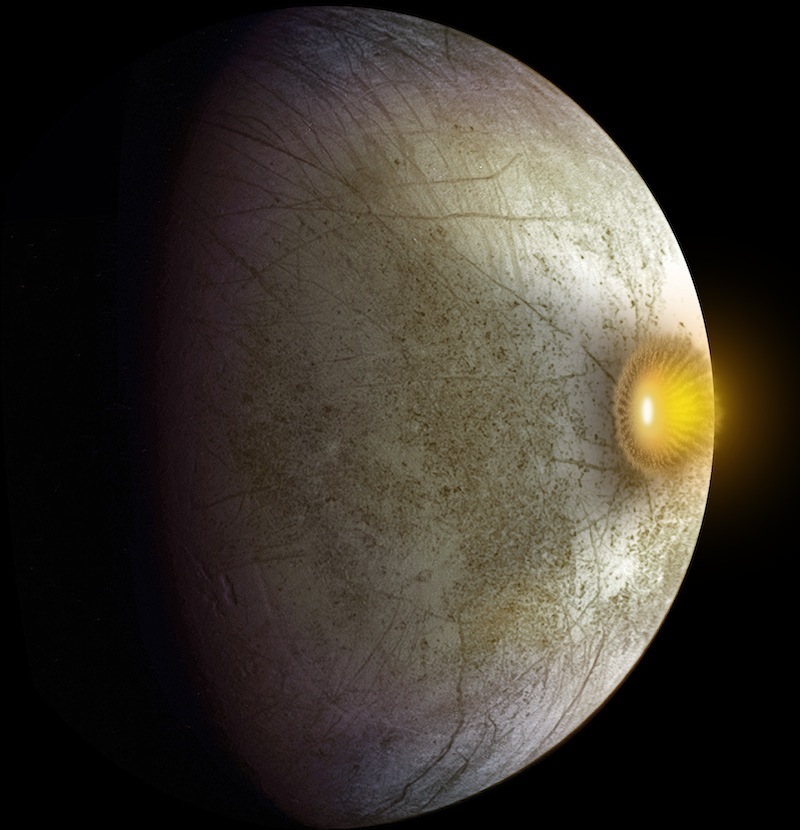

A new look at data from a NASA spacecraft has revealed evidence a colossal impact on Jupiter's moon Europa, a collision that may have delivered key minerals and perhaps even the raw ingredients for life, scientists say.

The cosmic crash scene, which NASA billed a "spectacular collision with an asteroid or comet," is the first time clay-like minerals have ever been detected on Europa. The discovery is based on a new analysis of images from NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter and is intriguing to scientists because comets and asteroids are often carriers of organic compounds, which can serve as ingredients for primitive life.

"Organic materials, which are important building blocks for life, are often found in comets and primitive asteroids," Jim Shirley, a research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement today (Dec. 11). "Finding the rocky residues of this comet crash on Europa's surface may open up a new chapter in the story of the search for life on Europa." [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

Scientists have held that Europa — one of more than 60 moons that circle Jupiter — may be one of the best places to look for extraterrestrial life in our solar system. Beneath its icy outer crust, the moon is thought to be hiding a saltwater ocean. Scientists have suspected that Europa is also home to organic materials, the carbon-based materials that make up the building blocks of life like proteins and DNA.

The new research supports the theory that comet or asteroid impacts could have delivered organic material to Europa. (Other research has suggested that space rocks also brought these seeds of life to Earth.)

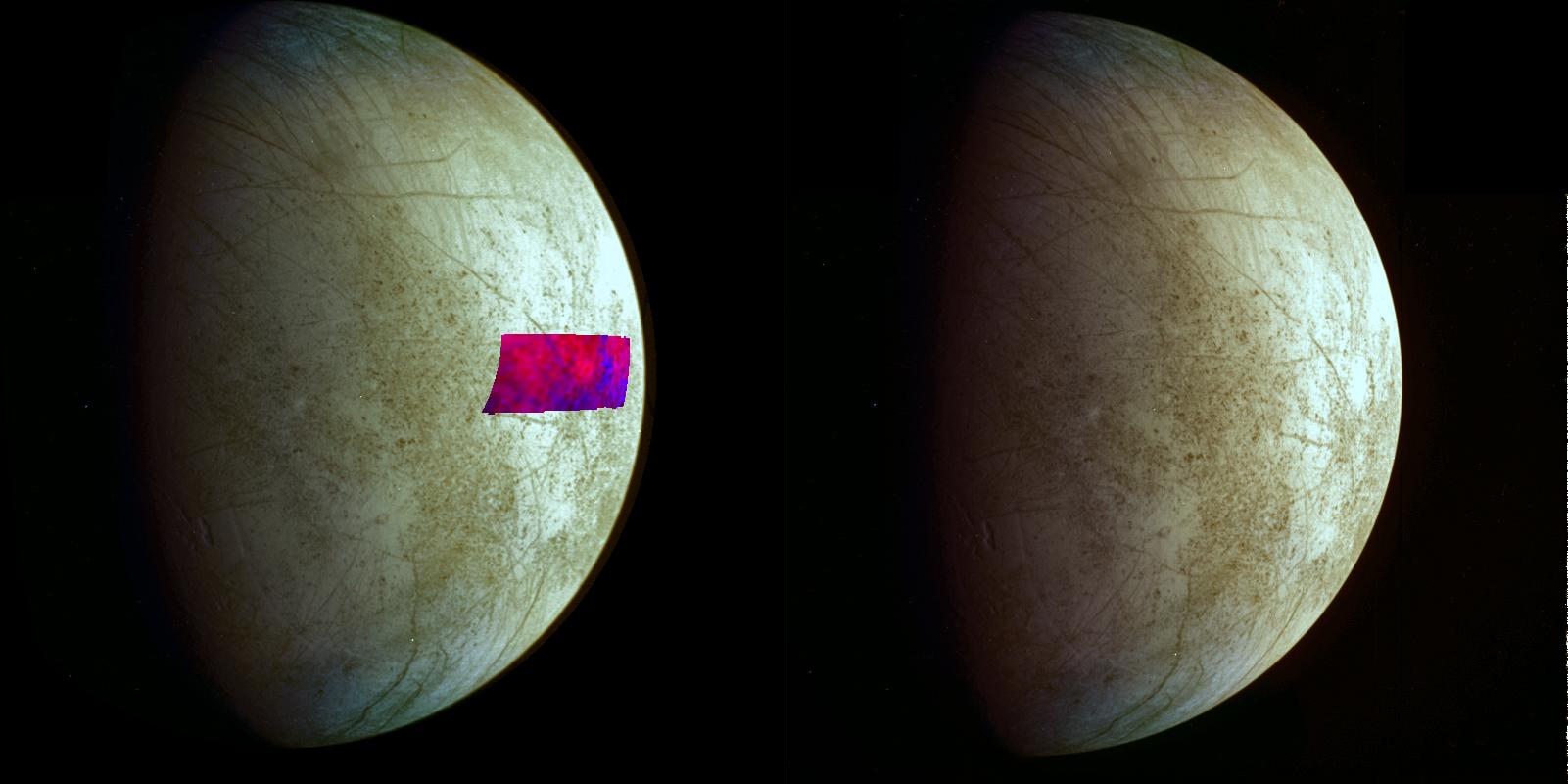

Shirley and colleagues made the discovery while looking at 15-year-old near-infrared images from NASA's Galileo spacecraft, which arrived at Jupiter in 1995 and circled the gas giant for eight years.

By today's standards, the resolution of the photos is quite low. But with new noise-eliminating techniques, Shirley and colleagues report they were able to see a broken ring of minerals called phyllosilicates about 25 miles (40 kilometers) wide in the landscape of Europa. (Phyllosilicates are clay-like minerals that form in the presence of water.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers say it is unlikely that these phyllosilicates on the surface came from Europa's interior; the moon's thick outer shell, up to 60 miles (100 kilometers) thick in some areas, would present a formidable obstacle. Instead, this broken ring may represent the splash-back of ejected materials scattered over Europa when a space rock hit the moon's surface from a shallow angle, the scientists say.

The phyllosilicate formation was located about 75 miles (120 km) away from the center of a 20-mile-diameter (30 km) crater site, the researchers say. Based on the size of this crater, the researchers think it may have been carved out by a 3,600-foot-wide (1,100 meters) asteroid, or perhaps a 5,600-foot-wide (1,700 meters) comet (similar in size to the recently deceased Comet ISON).

Another JPL scientist, Bob Pappalardo, who is working on a proposed mission to Europa, said researchers will need future missions to the moon to understand the specifics of Europa's chemistry and what it might mean for the possibility of life.

"Understanding Europa's composition is key to deciphering its history and its potential habitability," Pappalardo said in a statement.

The research, which was funded by a NASA Outer Planets Research grant, will be presented on Friday (Dec. 13) at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.