Smallest, Faintest Galaxies of the Ancient Universe Spotted

Two of NASA's most powerful space telescopes have teamed up to shed new light on the early history of the universe.

The Hubble Space Telescope utilized a natural zoom lens to capture nearly 60 of the smallest, faintest galaxies ever spotted in the distant universe. In a separate study, observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope helped researchers determine the masses of four of the brightest early galaxies after Hubble picked them out.

Both results could be followed up by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, an $8.8 billion observatory slated to be launched in late 2018, officials said. [The James Webb Space Telescope (Video)]

Seeing the previously unseen

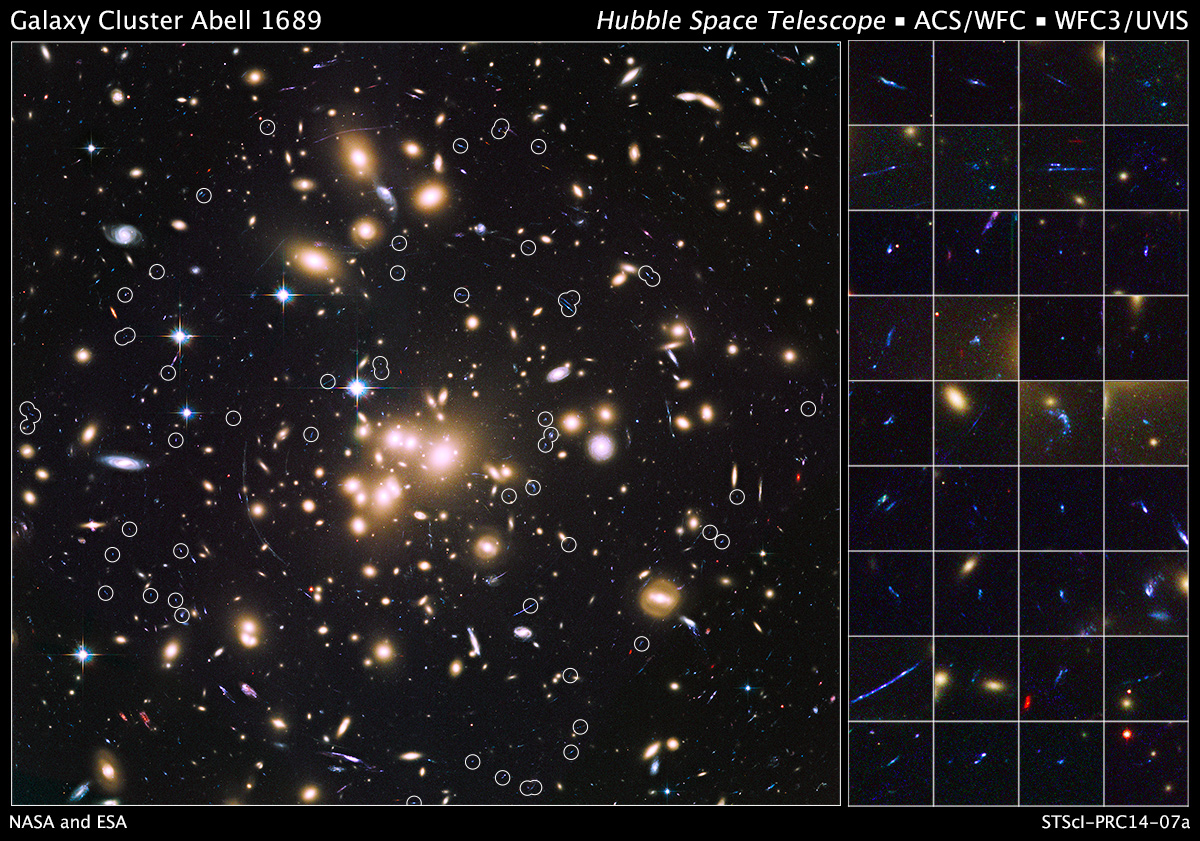

Deep exposures by Hubble captured images of the smallest, faintest, and most numerous galaxies ever seen in the distant universe as part of a three-year survey known as Frontier Fields.

Using ultraviolet light to trace star-forming regions, the telescope uncovered 58 small, young galaxies as they appeared more than 10 billion years ago, when the universe was less than 4 billion years old. (The Big Bang that created the universe is thought to have occurred around 13.8 billion years ago.)

About 100 times more numerous than larger galaxies, these galaxies are only a few thousand light-years across. Despite bursts of star formation that light them up in the ultraviolet spectrum, they are about 100 times fainter than other galaxies previously detected in deep-field surveys, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Most of the galaxies in the early universe have long been too faint to see.

"There's always been the concern that we've only found the brightest of the distant galaxies. The bright galaxies are only the tip of the iceberg," study leader Brian Siana, of the University of California, Riverside, said in a statement. "Now we have found those 'unseen' galaxies, and we're really confident that we're seeing the rest of the iceberg."

The dim galaxies have remained a mystery for so long because they are too faint for even Hubble to see unaided. The space telescope had to utilize the magnifying glass created by an alignment of a galaxy cluster, Abell 1689, lying between the Earth and the faint galaxies.

Because of a process known as gravitational lensing, the massive cluster distorts the space-time around it, bending and magnifying the light from the galaxies behind it. Without the lenses, many of the galaxies would appear only as points of light to Hubble. [Massive Galaxy Cluster Warps Space, Reveals What's Behind It (Video)]

"Though these galaxies are really faint, their increased numbers mean that they account for the majority of star formation during this epoch," lead author Anahita Alavi, also at the University of California, Riverside, said in the same statement.

The faint stars fill in some missing entries in the galactic census when the universe was just 3.4 billion years old or so, researchers said. Galaxies such as these may have helped to strip the electrons off the hydrogen gas that permeated the universe about 13 billion years ago in a process known as reionization, making the universe transparent to light and allowing present-day astronomers to make distant observations.

"Although the galaxies in our sample existed a few billion years after reionization, it's presumed that galaxies like these, or possibly some of these galaxies, did play a big role in reionization," Siana said.

The team continues to search for other faint, distant galaxies using other clusters as gravitational lenses.

The results were presented Tuesday (Jan. 7) at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Washington.

The brightest ancient galaxies

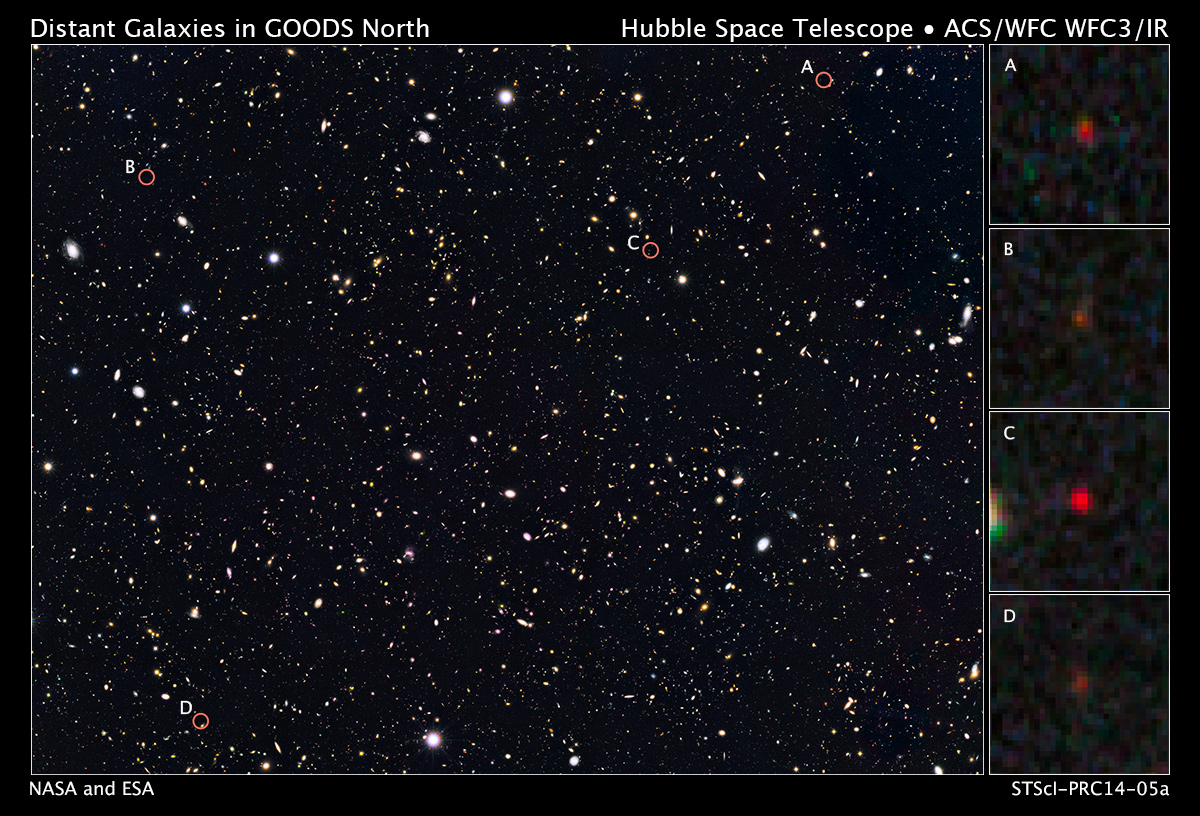

The faintest galaxies weren't the only ones to be represented at the AAS meeting Tuesday. A second team, working independently with Hubble, presented four distant galaxies that outshone their neighbors, which they found in one of the two Great Observatories deep survey fields.

The galaxies, which appear to astronomers as they did when the universe was only about 500 million years old, are up to 20 times brighter than anything of that vintage seen previously.

"These just stuck out like a sore thumb because they are far brighter than we anticipated," Garth Illingworth of the University of California at Santa Cruz said in a statement. Illingworth was part of an international team of astronomers that measured the ancient galaxies.

"We're suddenly seeing luminous, massive galaxies quickly build up at such an early time," Illingworth added. "This was quite unexpected."

Astronomers found the galaxies using Hubble, which allowed them to measure their size and star-formation rates. Follow-up studies using Spitzer provided estimates of stellar masses, based on the luminosities of the galaxies.

"This is the first time scientists were able to measure an object's mass at such a huge distance," Pascal Oesch, who was at the University of California, Santa Cruz during the study, said in the same statement. "It's a fabulous demonstration of the synergy between Hubble and Spitzer."

Although only one-twentieth the size of the Milky Way, the galaxies form stars almost 50 times as fast. The rapid pace of star formation most likely accounts for their unusual brightness. Scientists think that the galaxies formed through the interactions and mergers of many smaller galaxies.

When the James Webb Space Telescope is launched, it should be able to see these and other bright, growing galaxies in the young universe, researchers said.

"The extreme masses and star formation rates are really mysterious," Rychard Bouwens, of Leiden University in the Netherlands, said in a statement. "We are eager to confirm them with future observations on our powerful telescopes."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd