Spot Huge Asteroid Pallas in the Night Sky This Week

Although asteroids figure prominently in doomsday predictions, science-fiction stories and video games, most stargazers have never actually seen one with their own eyes.

This week you will get an excellent opportunity to observe one of the largest asteroids, Pallas, as it passes close to Earth. (Don't worry — there is no chance the enormous space rock will hit our planet.)

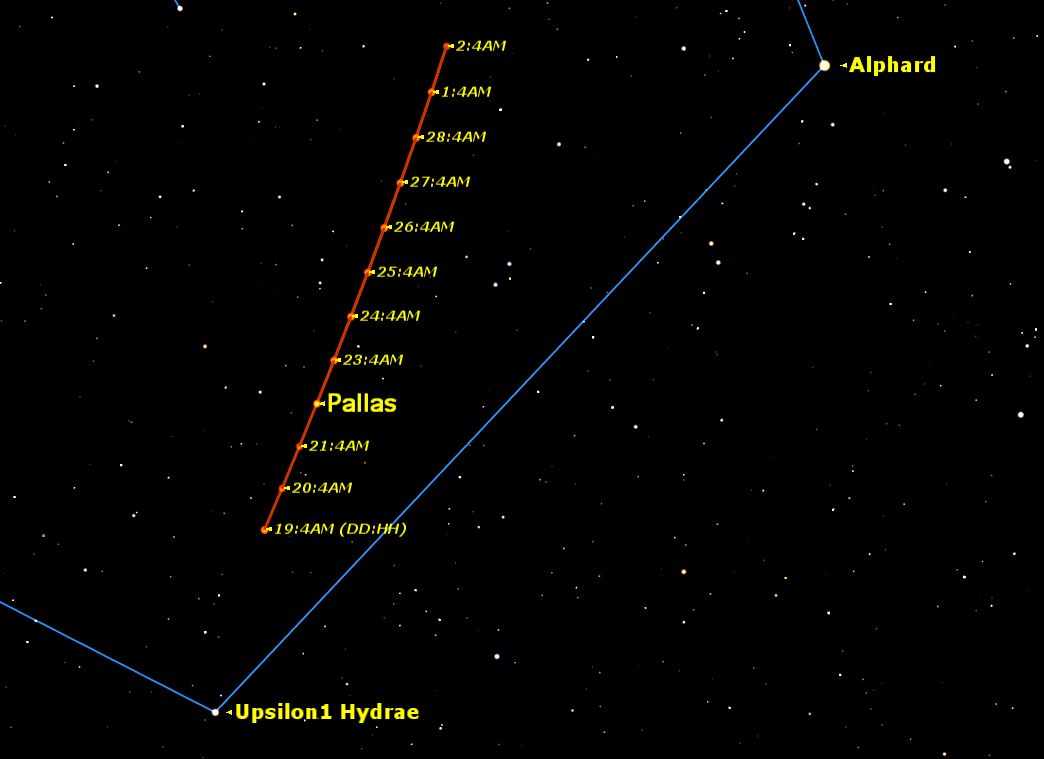

Over the next couple of weeks, Pallas will be moving rapidly through the constellation Hydra, just south of Leo. Because its orbit is tilted 35 degrees to the ecliptic plane of the solar system, Pallas will appear to move almost north to south. [See photos of potentially dangerous asteroids]

Locate Pallas using Alphard, the brightest star in Hydra. Currently Alphard is highest in the southern sky around midnight. Use Algieba and Regulus as "pointers" to locate Alphard; although only second magnitude, it is the brightest star in this part of the sky.

Next, look for Upsilon1 Hydrae, a 4th-magnitude star located 8.5 degrees below and to the left of Alphard. Then use the chart to locate Pallas relative to these two stars on the night you are observing. Pallas will look just like an 8th-magnitude star. Plot its position relative to the stars around it, and you will see that it moves noticeably after only a few hours. This is the only way to be sure which "star" is really the asteroid.

Pallas will be between 6th- and 7th-magnitude, just too faint to see with the naked eye, but easily visible in binoculars. Pallas will be slightly brighter than most of the stars between Alphard and Upsilon1; therefore, it should be relatively easy to spot.

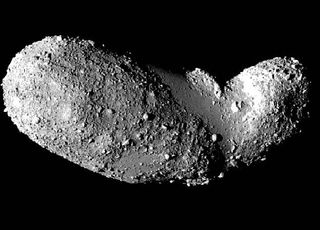

The name "asteroid" was given to bodies like Pallas because, even in the most powerful telescopes, they look like stars. This is because of their relatively small size.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The largest asteroid, Ceres, is 596 miles (959 kilometers) in diameter, and the second- and third-largest, Pallas and Vesta, are both around 320 miles (520 km) in diameter. By comparison, the moon is 2,159 miles (3,475 km) in diameter.

Most asteroids in the solar system are located in orbits falling between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, the so-called asteroid belt. This name leads to the misconception of a band of small rocks.

The reality is far different. Actual asteroids — though numbering in the millions — are separated by large distances. Standing on any one asteroid, you would need binoculars to see the nearest asteroids. Navigating through the asteroid belt is very easy, since it is essentially empty space. The chance of hitting an asteroid is virtually zero.

Ceres is large enough to have been pulled into a spherical shape by gravity. Smaller asteroids like Pallas are more irregular in shape.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing picture of Pallas or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com bySimulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.

Most Popular